A low-cost play-based programme for refugee mothers and their children in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh was remarkably effective at improving mental health and wellbeing

Forced displacement, such as that experienced during the Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh, significantly increases the risk of mental health disorders among affected populations. Women and children are most vulnerable due to displacement-related trauma, discrimination, and limited healthcare access in refugee camps. We urgently need to find interventions that can effectively address this humanitarian issue.

In partnership with BRAC, for our research (Islam, Mojumder, Rahman, Shatil and Siddique 2024) we ran a large-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) in refugee camps in Bangladesh, targeting Rohingya mothers and their children under the age of two. We worked closely with the BRAC Institute of Educational Development (BIED) and the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) in Bangladesh to develop a simple, low-cost, multifaceted psychosocial programme. This programme has improved the mental wellbeing of mothers and facilitated positive developmental outcomes for their children.

Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh

The Rohingya people, an ethnic minority from Myanmar, have faced decades of persecution leading to mass displacement, peaking in 2017. Over one million Rohingya refugees now live in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district, with women and children facing severe physical and mental health challenges. About 52% of Rohingya refugees are females. Over 80% of Rohingya women reported having depressive and emotional distress symptoms, and 60% had post-traumatic stress disorders after fleeing violence in their home country (Fortify Rights 2020). In the refugee camps, women often experience various forms of abuse by intimate partners, relatives, or other camp members. About 30,000 children are born annually in the camp, which gives an idea of the dire need for proper maternal and child health care support for Rohingya women and their children, particularly given the fact that seeking healthcare outside camps is not possible as mobility is restricted to their designated camps.

Children represent about 55% of the one million Rohingya refugees residing in the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh, of which 41% are children under the age of 11 and 18% under the age of four. Malnutrition is a major concern, with 50% of Rohingya children underweight and suffering from anaemia. Of those under five, 25% are acutely malnourished, and 38% are stunted (WHO Situation Report 2017). Mental health is also a critical issue, as one is five Rohingya refugee children having severe mental distress.

The Home-Based Humanitarian Play Lab (HPL) programme

In partnership with BRAC, we conducted a large-scale RCT targeting Rohingya mothers and their children under two years old. The programme focused on psychosocial education and play-based activities and was facilitated by trained Rohingya women called Mother Volunteers (MVs), who were recruited from the same neighbourhoods as the participants. Sessions included psychoeducation, parenting support, and engaging play sessions for children, using locally available resources. Therefore, our interventions were peer-directed. MVs were trained by mental health and early-childhood experts and received support (when required) by expert counsellors during the intervention period.

The HPL sessions were structured to address various aspects:

- Greeting and Relaxation: Opening with breathing exercises to induce relaxation.

- Mental Health Support for Mothers: Discussions on self-care, positive thinking, and coping mechanisms, accompanied by interactive games and art activities.

- Parenting Support: Guidance on childcare practices and the importance of play for child development, integrated with hands-on play activities.

- Homework Assignments: Weekly tasks for mothers to reinforce learning and practice.

Our RCT involved about 3,500 mother-child dyads. The treatment group received the hour-long intervention weekly for a year, from October 2019 until September 2020. They attended small group sessions in their designated MV’s house. The control group attended unstructured social gatherings, where they experienced the intervention’s social aspect but not its specific content. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Bangladesh went into a nationwide lockdown, stopping the programme from late March 2020. Over-the-phone support replaced face-to-face sessions, which began in mid-May 2020 and ended in late September 2020. To accommodate over-the-phone sessions, session duration and structure were carefully revised by experts from BIED.

Measuring mental health?

We broadly explore psychological trauma by combining post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD), as their symptoms overlap. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), these disorders primarily develop after experiencing traumatic events involving actual or threatened violence, serious injury, or death. To assess psychological trauma, we used the simplified Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Andrews and Slade 2001) and combined it with survey questions developed following the PTSD and ASD diagnostic criteria in the American Psychiatric Association (2013). We also measure depression, which is a mental disorder characterised by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, loss of interest in activities, and changes in sleep, appetite, and energy levels. It can significantly disrupt a person’s daily life and functioning. We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale 20 or CESD-20 (Radloff 1977), a well-validated self-report tool that assesses the frequency and severity of depressive symptoms. We measured children’s psychological trauma and depressive symptoms through an adverse life experience survey (Dyregrov et al. 2000, Neugebauer et al. 2009), which were answered by the mothers.

Our findings

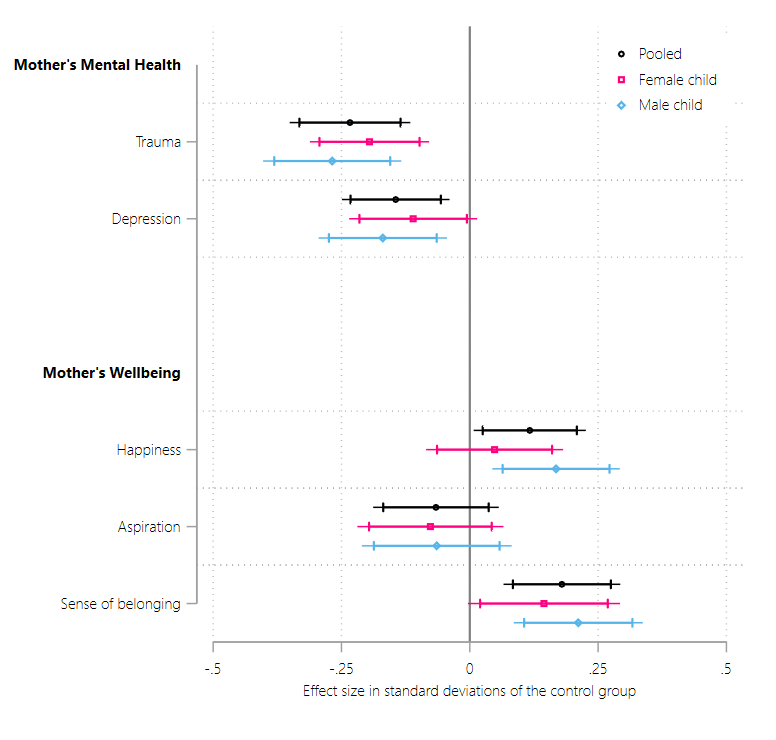

The intervention significantly improved the mental well-being of both mothers and children. Mothers reported reduced psychological trauma (by 0.23 standard deviations or 16%) and depressive symptoms (by 0.14 SD or 13%) relative to mothers in the control group who did not receive the psychosocial intervention. We observed considerably higher improvement in mental wellbeing among women who reported to have moderate to severe depression and psychological trauma at baseline. Mentally unhealthy mothers that received the treatment not only experienced improvements, but often surpassed the mental health scores of mothers in the control group who were initially considered “mentally healthy”. This suggests the intervention can effectively lift refugee mothers out of psychological distress. We report these results in Figure 1.

Figure 1

As also shown in Figure 1, mothers reported feeling happier after the intervention (0.12 SD or 4% higher than the control group). An increase in happiness of 4%, while seemingly small, indicates a shift towards more positive emotions and experiences of refugee women. We also find that mothers reported feeling a greater sense of connection and belonging within their new community following the intervention (0.18 SD or 5% higher than the control group). This is an important result because refugees often struggle with isolation and lack of appreciation. We, however, do not observe significant improvements in future aspirations of refugee women. Therefore, our study shows that improved mental health can increase happiness and facilitate a stronger sense of belonging.

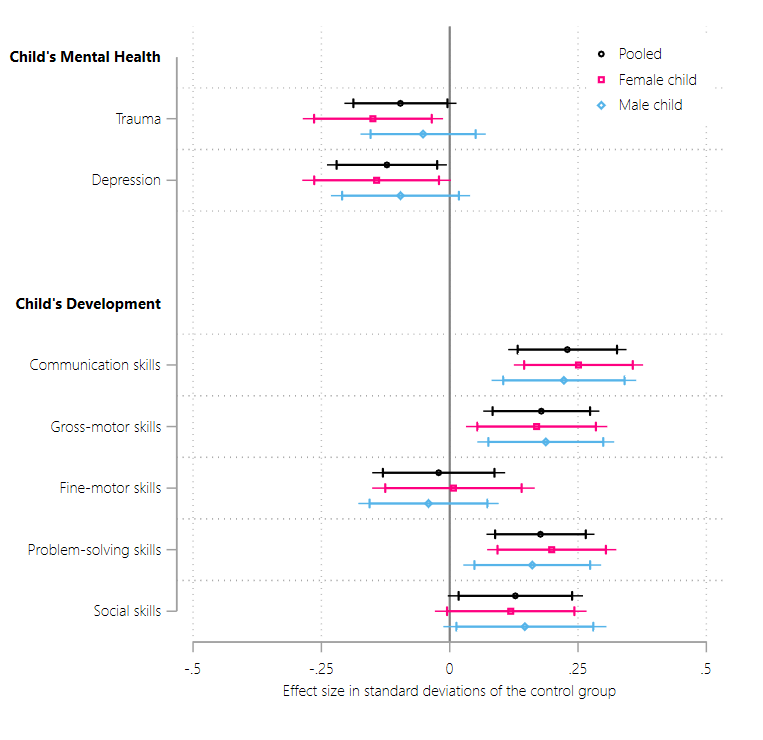

Figure 2

As seen in Figure 2, the intervention impacted children in the treatment group in a number of positive ways. Children experienced a significant reductions in psychological trauma (by 0.10 SD or 11%) and depressive symptoms (by 0.12 SD or 13%) relative to children in the control group.

Children also demonstrated improvements in (relative to control-group children):

- communication skills (i.e., speech and language development) by 0.23 SD or 8%

- gross-motor skills (i.e. physical activities and whole-body movements) by 0.18 SD or 5%

- problem-solving skills (i.e. learn to play with toys and solve puzzles) by 0.18 SD or 7%

- personal-social skills (i.e. care for themselves and interactions with others) by 0.13 SD or 6%

However, we do not observe any change in fine motor skills of treated children. The intervention’s focus on movement, play, and larger muscle groups likely explains the significant improvements in gross-motor skills and not fine-motor skills. Furthermore, we find that the intervention positively impacted physical growth and nutritional status of the children who received the treatment.

These findings demonstrate that the HPL intervention was largely successful at lifting refugee mothers out of psychological distress and potentially prevented long-term mental illness, such as persistent depressive disorder. In fact, the intervention was successful at reducing the mental health gap (both in terms of psychological trauma and depression) between mothers and their children, possibly because it allowed children to absorb and integrate the mental health of their mothers due to increased interactions. This further suggests that interventions targeting the mental well-being of mothers can be an important stepping stone to developing psychological resilience among their children.

Policy implications

BRAC’s home-based HPL intervention has proven remarkably effective and cost-efficient. With support from international donors, the programme has scaled up to reach about 40000 mother-child pairs. This success highlights the importance of investing in mental health support for refugee women, particularly considering the intergenerational benefits observed. These findings urgently call for policy initiatives that prioritise mental health support for refugees worldwide.

In a world facing numerous refugee crises, targeted interventions like the HPL programme are important. By addressing the psychological needs of refugee mothers and children, we reduce their immediate distress but also lay the foundation for long-term resilience and well-being. While limitations within Rohingya refugee camps prevented us from directly measuring labour market impacts or income changes of refugees (as they are not legally allowed to work), the relationship between mental health and economic outcomes is well-established. As new crises emerge, such interventions become beacons of hope, offering vulnerable populations worldwide a path towards healing and empowerment, and the potential for improved economic opportunities.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013), "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders", 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Andrews, G and T Slade (2001), "Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10)", Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(6): 494–497.

Beech, H (2017), "'I’m Struggling to Survive': For Rohingya Women, Abuse Continues in Camps", New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/23/world/asia/rohingya-women-abuse-myanmar.html. Accessed September 12, 2020.

Dyregrov, A, L Gupta, R Gjestad, and E Mukanoheli (2000), "Trauma exposure and psychological reactions to genocide among Rwandan children", Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(1): 3–21.

Fortify Rights (2020), "The Right to Mental Health for Rohingya Survivors of Genocide in Myanmar and Bangladesh", Available online at: https://www.fortifyrights.org/mya-inv-rep-2020-12-10/. Accessed January 04, 2022.

Islam, A, T Mojumder, T Rahman, T Shatil, and A Siddique (2024), "Forced Displacement, Mental Health, and Child Development: Evidence from the Rohingya Refugees", Working Paper, Monash University.

Radloff, L S (1977), "The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population", Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3): 385–401.

WHO Situation Report (2017), "WHO Weekly Situation Report no. 8", Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/searo/bangladesh/bangladesh---rohingya-crisis---pdf-reports/sitreps/2017/weekly-sitrep08-cxbban.pdf?sfvrsn=dc203c83_2. Accessed October 01, 2020.