Colonial medical campaigns in Central Africa have had lasting impacts, worsening health outcomes and lowering World Bank health project success today

Demand for health interventions is often low in developing countries, despite modern health interventions drastically improving in efficacy and decreasing in costs. Health interventions often fail because of low demand by the final consumers (Dupas 2011, Dupas and Miguel 2017). For example, polio vaccination campaigns have been unable to reach herd immunity levels due to vaccination refusals in Cameroon (Kindzeka 2015). Another example comes from the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa, during which some communities were suspicious of doctors and refused treatment (Neporent 2014). Thus, even when many supply and quality issues have been addressed, demand for high-quality preventative and therapeutic tools remains low.

Our study

In a recent study (Lowes and Montero 2018), we examine one potential cause of the low demand for and subsequent ineffectiveness of health interventions: historical exposure to colonial health campaigns. We focus on medical campaigns conducted by the French military in Cameroon and former French Equatorial Africa (AEF) to combat sleeping sickness. These campaigns forced individuals, often at gunpoint, to receive treatment with drugs with serious side effects. We link these campaigns to: mistrust in medicine, worse health outcomes, and lower World Bank health project success.

Description of the campaigns

Between the 1920s and 1950s, the French military undertook extensive medical campaigns aimed at managing tropical diseases. In Cameroon and former AEF (present day Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of Congo, and Gabon), the French military organised mobile medical teams to combat sleeping sickness, a lethal disease spread by the tsetse fly. Millions of individuals were subjected to medical examinations and forced to receive injections of various medications to treat or prevent sleeping sickness. These medications had dubious efficacy and serious side effects, including blindness in up to 20% of individuals, gangrene, and death. The campaigns constituted some of the largest colonial health investments, and for many, these campaigns were their first exposure to modern medicine (Headrick 1994, Lachenal 2014).

Medical campaigns and mistrust in medicine

Motivated by work from anthropology and history, we hypothesise that the colonial medical campaigns may have had a series of unintended effects on both beliefs about modern medicine and the success of modern health interventions. Anthropologists and historians have linked the colonial medical campaigns against sleeping sickness to mistrust in medicine. For example, regarding tetanus campaigns in Cameroon in the 1990s, Feldman-Savelsberg et al. (2000: 162) note, “[The tetanus campaigns] awakened negative collective memories of French colonial medical efforts to wipe out sleeping sickness”.

Measuring campaign exposure and trust in medicine

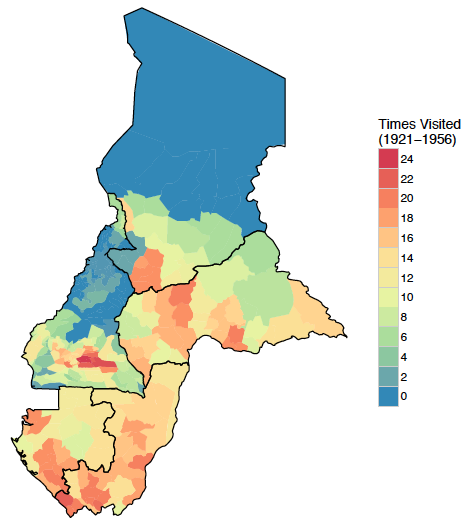

To measure exposure to colonial medical campaigns, we construct a dataset from over 30 years of archival data from French military archives for five countries. We digitise data documenting the locations of sleeping sickness campaign visits at a granular geographic level between 1921 and 1956. We measure exposure to the campaigns as the share of years that a location is visited during the years of the campaigns.

Figure 1 Map of campaign visits

There are no self-reported measures of trust in medicine available for our area of interest. However, we measure trust in medicine by whether an individual consents to a free and non-invasive blood test for either anaemia or HIV in the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). We consider consent to the blood tests to be a revealed preference measure of trust.

Results: Campaigns and mistrust in medicine

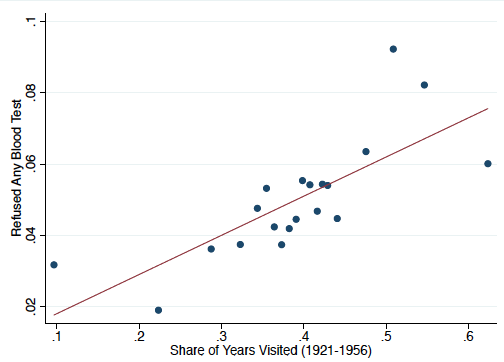

We find that increased exposure to colonial medical campaigns is correlated with lower levels of trust in medicine today. Approximately 4.7% of the sample refuse the blood tests. Being visited by the colonial medical campaigns for 15 years, the average number of years an area is visited, increases refusals by 5.1 percentage points. The results are robust to a variety of geographic, colonial, pre-colonial, and individual level controls. The strong correlation remains when we examine anaemia or HIV refusals separately.

Figure 2 Binscatter plot of refusals and campaign visits

Instrumental variables strategy

Of course, the campaigns may have targeted particular areas, that either were already less trusting or that have another characteristic that jointly determines trust in medicine and colonial medical campaign visits. To deal with these concerns, we construct an instrumental variable based on an interaction between distance to colonial capital, which proxies for the ease with which mobile medical teams would be able to access an area, and suitability for cassava relative to millet, which proxies for likelihood of exposure to tsetse fly habitat. Our instrumental variable estimates are consistent with the OLS estimates: being visited for 15 years increases refusals by 6.5 percentage points, leading to a doubling in the refusal rate.

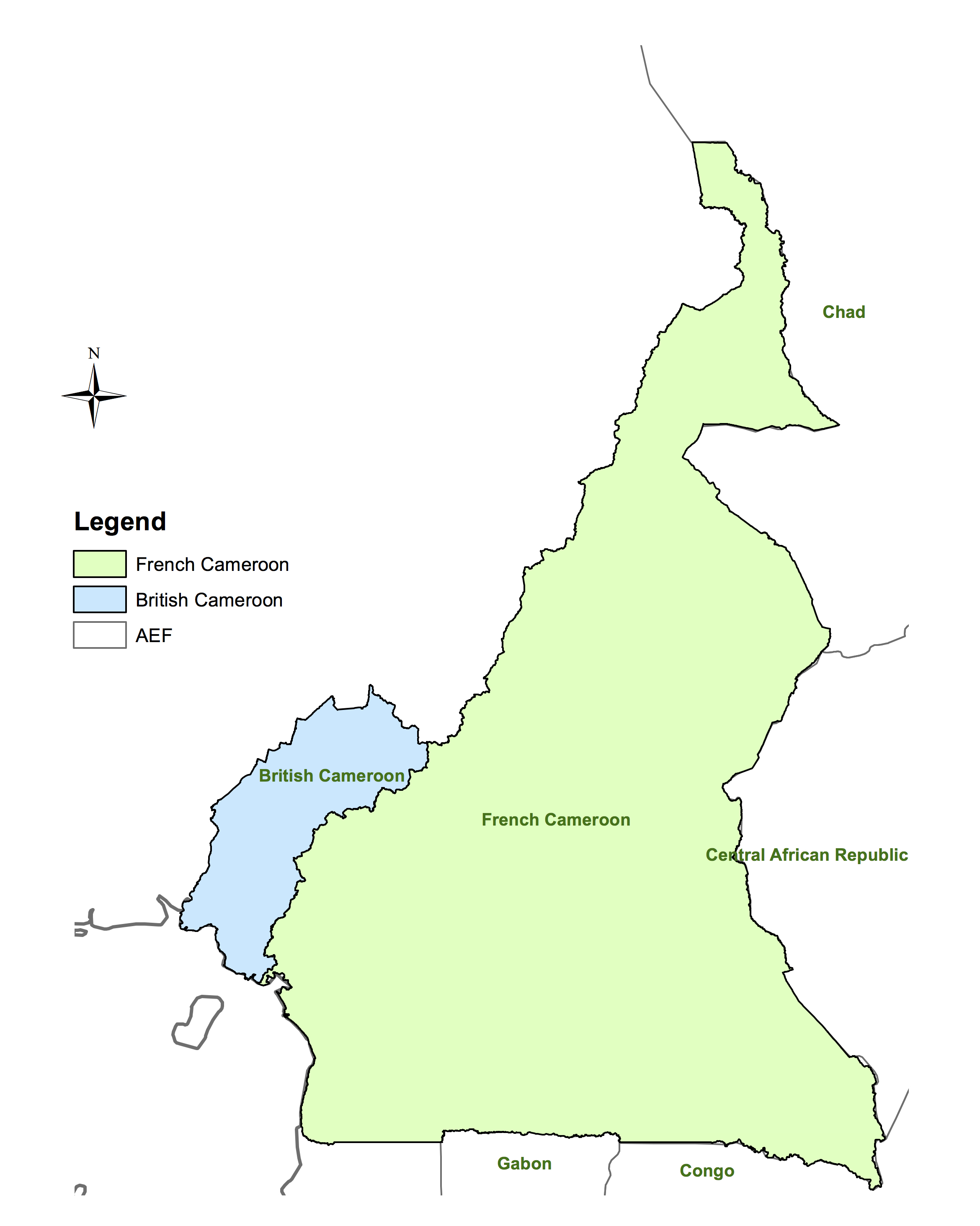

We use the unique history of Cameroon, which was divided between the French and British after WWI, to test whether our instrument directly affects trust in medicine. The British did not conduct equivalent campaigns in their part of Cameroon, thus the instrument should not predict refusals there. Reassuringly, we find that the instrument only has predictive power in former French Cameroon.

Figure 3 British and French Cameroon

Trust in other people or institutions

We also explore whether the observed mistrust is specific to trust in medicine, or if it extends to trust in other people or institutions using Afrobarometer data from Cameroon and Gabon. We find that there is no effect of exposure to the medical campaigns on trust in a variety of non-medical individuals and institutions, suggesting that the effect of exposure to medical campaigns is specific to the medical domain.

Effects on childhood vaccinations, anaemia, and HIV

Given that the health campaigns predict measures of trust in medicine, we examine the implications for health outcomes. In areas with greater exposure to the campaigns children are less likely to have been vaccinated. A one standard deviation increase in colonial medical campaign visits reduces vaccination rates of children by 0.064 standard deviations. Second, we examine the outcomes for the two blood tests administered in the DHS, with the caveat that our previous analysis shows selection into who consents to take the blood test. We find evidence of higher levels of anaemia and HIV in areas with greater exposure to the campaigns.

Colonial medical campaigns and World Bank Project success

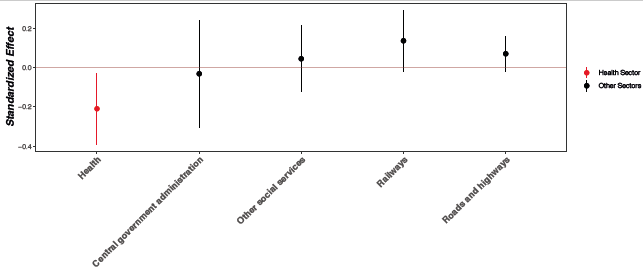

Finally, we examine the relevance of historical medical campaigns for present day health policy. We use data on the location of World Bank projects approved between 1995 and 2014 to examine how exposure to medical campaigns affects project success as rated by the World Bank. The World Bank rates projects on a 6-point scale from ''highly unsatisfactory'' to ''highly satisfactory''. We compare the ratings of health projects and non-health projects by historical medical campaign intensity.

We find that greater exposure to the campaigns is correlated with lower health project ratings, but there is no similar effect on the ratings of projects in other domains. The effect size of historical medical campaigns for health project ratings for areas with the average exposure to the campaigns is equivalent to changing the rating from "moderately satisfactory" to "moderately unsatisfactory".

Figure 4 Project rating coefficients plot

Conclusion

The historical medical campaigns provide several important lessons for present day development policy. First, top-down aid implemented poorly and without local consent and involvement can have long lasting unintended consequences. Second, the success of present day health interventions or policies may depend on the historical experiences of the target populations. Finally, building and maintaining trust in medicine should remain a priority for modern health policy.

References

Dupas, P(2011), “Health behaviour in developing countries,” Annual Review of Economics 3: 425–449.

Dupas, Pand E Miguel (2017), “Impacts and determinants of health levels in low-income countries,” in Duflo, E and A Banerjee (eds.), Handbook of field experiments, Vol. 2, North Holland.

Feldman-Savelsberg, P, F Ndonko and B Schmidt-Ehry (2000), “Sterilising vaccines or the politics of the womb: Retrospective study of a rumour in Cameroon,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14(2): 159–179.

Headrick, R (1994), Colonialism, health and illness in French Equatorial Africa, 1885-1935, African Studies Association Press.

Kindzeka, M (2015), “Cameroon finds resistance to polio vaccination campaign,” Voice of America News.

Lachenal, G (2014), Le médicament qui devait sauver l’Afrique (The hidden story of the medicine meant to save Africa), La Découverte.

Lowes, S and E Montero (2018), “The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa,” Working Paper.

Neporent, Liz (2014), “Doctors battling Ebola are met with fear, mistrust,” ABC News.

Pépin, J (2011), The origins of AIDS, Cambridge University Press.