China's high-stake judicial reform boosts local court independence, curbs protectionism in cross-region lawsuits, and stimulates investment flows between regions

An impartial legal system that enforces contracts and property rights under the rule of law has long been perceived as a fundamental building block of economic prosperity (Smith 1937, North 1986, Besley and Persson 2011, Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). As a core principle of the separation of powers, judicial independence is necessary to prevent improper political influence over the courts, thereby enabling the legal system to play its key role in providing fair trials, settling commercial disputes, and maintaining a competitive market environment (Hamilton 1788, Hayek 1960, Buchanan 1974).

In reality, the degree of judicial independence from political influence varies substantially across the globe and is on average substantially lower in developing economies and civil law countries (Glaeser and Shleifer 2002, La Porta et al. 2008). In such settings, political capture of judiciaries is far from uncommon, as local governments frequently interfere with judicial decisions to favour local firms over external ones (Cooter, 1996; Hay and Shleifer, 1998). Such judicial local protectionism impedes the formation of profitable business relations and deters economic integration between regions. While there exist strong cross-country correlations between court capture and various politico-economic conditions (Djankov et al. 2003, La Porta et al. 2004, La Porta et al. 2008), there has been little rigorous, causal evidence on how court capture affects judicial decisions and economic activities.

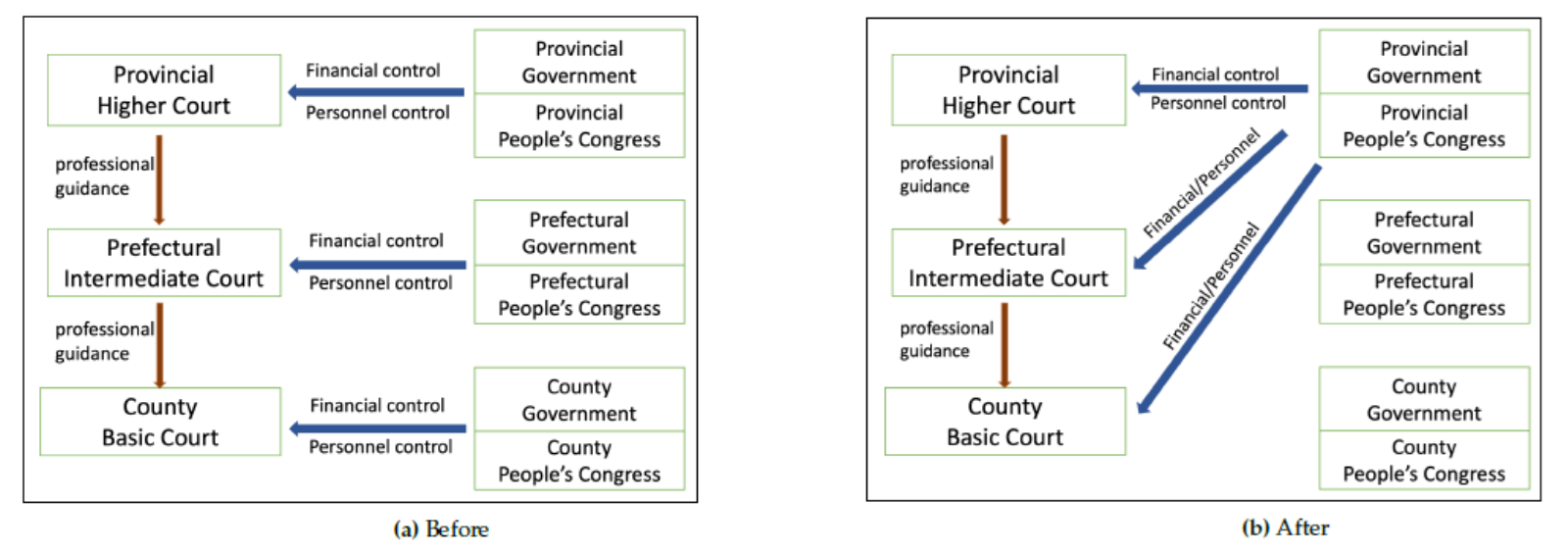

China provides an ideal empirical setting to study the economic impact of court capture for two unique institutional features. First, historically, local governments in China held significant control over local courts. This fact, combined with the country's high levels of economic decentralisation, led to ubiquitous judicial local protectionism in handling commercial lawsuits (Gong 2004, Xu 2011, Li 2012, Ng and He 2017, Wang 2018). Second, since 2014, the Supreme People’s Court has been gradually rolling out a high-stakes judicial organisational reform that aims to alleviate court capture by taking away local governments' financial and personnel controls over local courts. The organisational changes created by the reform and the detailed roll-out schedule of the reform are shown in Figure 1. Extensive anecdotal observations by legal scholars, judges, and lawyers testify that the reform has significantly transformed China's judicial system (Zhou 2017, Chen 2018, Zhang and Ginsburg 2019, Supreme People’s Court 2019).

Figure 1: Judicial organisational reform, incentive structure changes and geographical expansion

Notes: Panel (a) demonstrates the administrative structure of China’s local judiciaries before the judicial organisational reform. Panel (b) demonstrates the administrative structure of China’s local judiciaries after the judicial organisational reform. Panel (c) illustrates the roll-out schedule of the reform across the country.

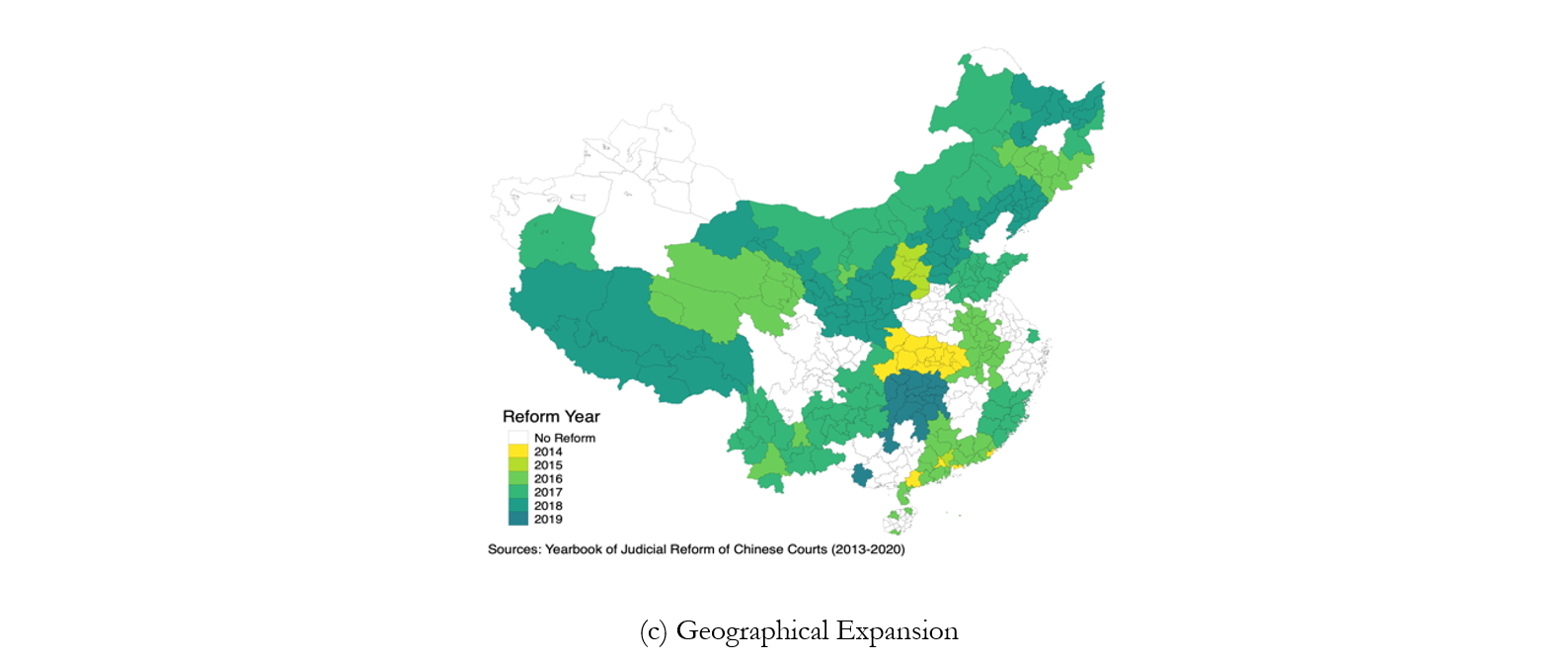

In recent research (Liu et al. 2023), we provide novel and rigorous empirical evidence on the impact of alleviating court capture on judicial local protectionism and economic integration, in the context of China. We compile administrative data on the universes of Chinese court verdicts between 2014 and 2021 (133 million cases) and business registration records between 1978 and 2021 (75 million registries). Exploiting the staggered roll-out of the judicial organisational reform since 2014, we document that the reform has significantly reduced local protectionism in judicial decisions. As shown in Figure 2(a), following the reform, the win rate of local defendants against external plaintiffs dropped by 3.3 percentage points, which is a 7.3% reduction from the baseline average win rate of local defendants. The decline in the win rate is especially large for politically connected local defendants, consistent with these firms receiving more local protection pre-reform. Such a reduction in judicial local protectionism also encourages more small non-local firms to bring lawsuits against their large local counterparts in the longer run, as illustrated by Figure 2(b).

Figure 2: Judicial organisational reform and judicial impacts

Notes: In Panel (a), we plot the event study coefficients (and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals) using the local defendant’s win rate as the outcome variable. In Panel (b), we plot the event study coefficients (as well as 95% confidence intervals) using the share of outcome external plaintiff against local defendant cases over all cases between companies as the outcome variable. All event studies are estimated following the approach suggested by Sun and Abraham (2021).

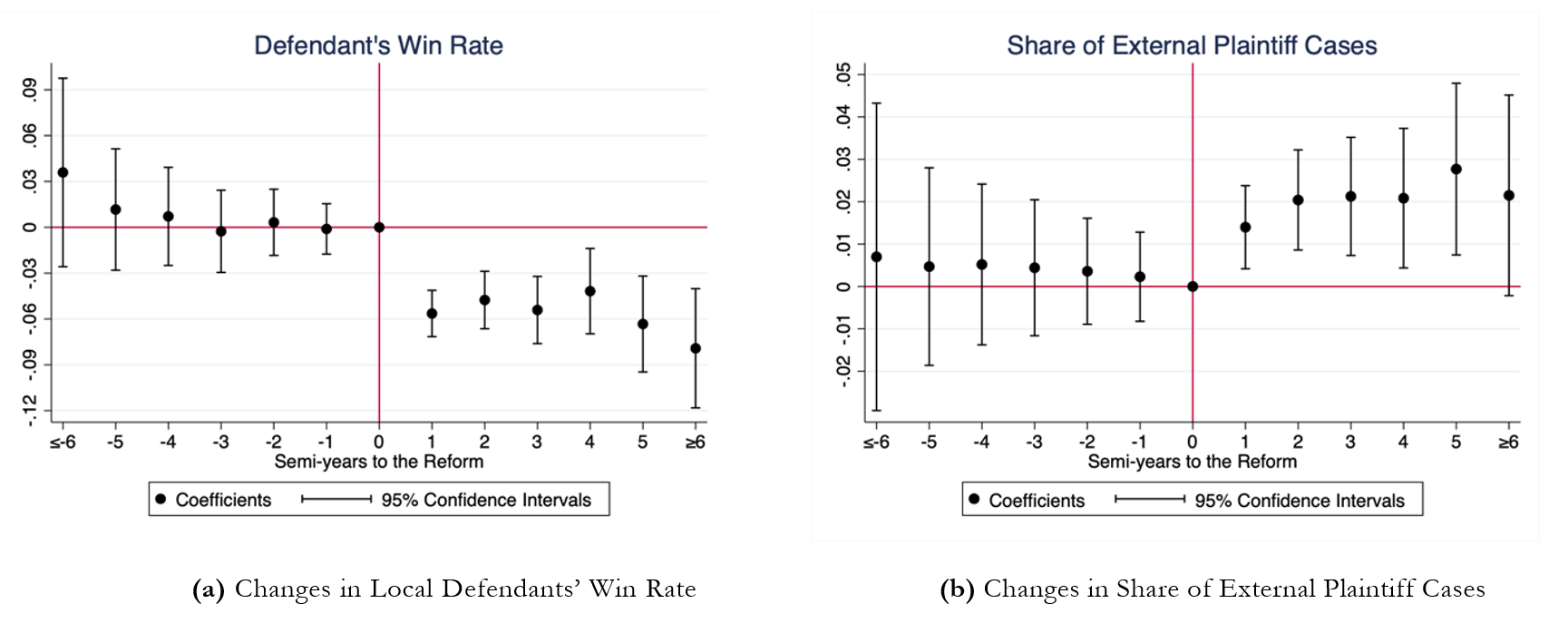

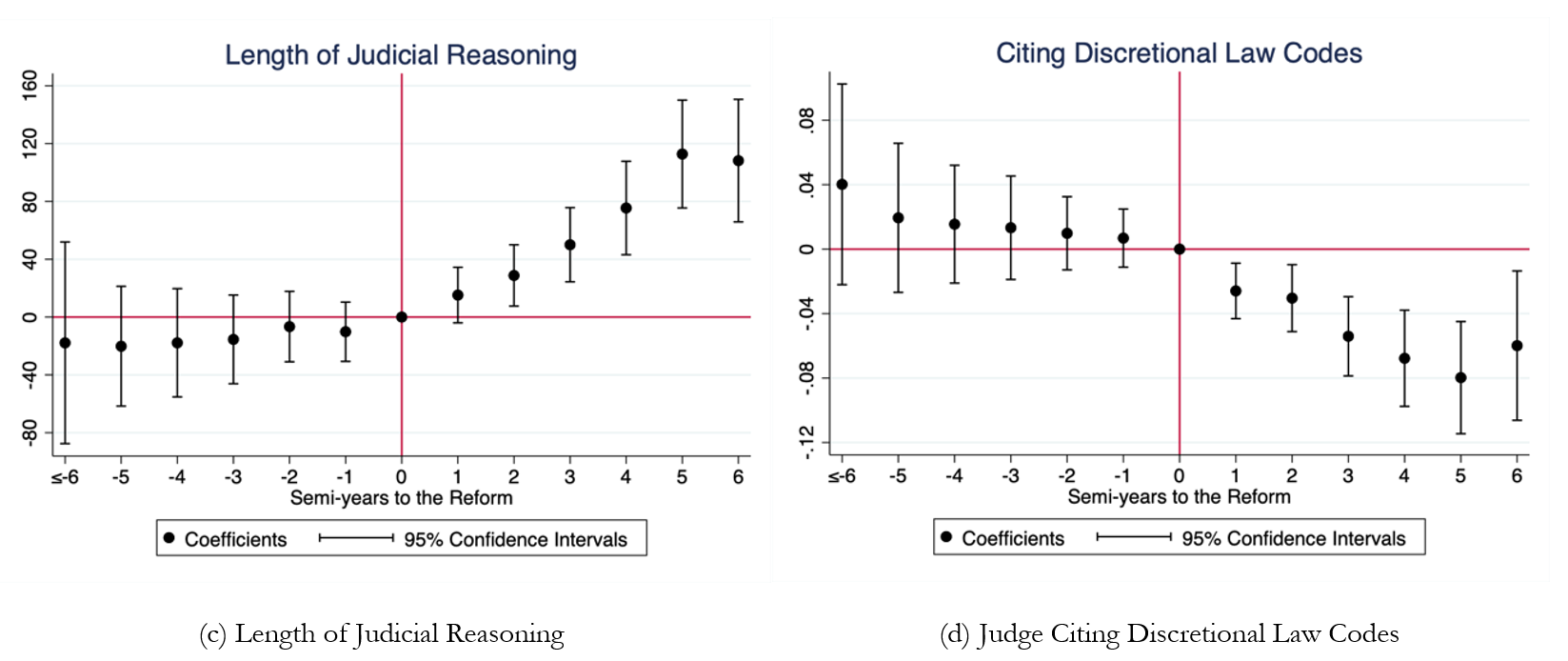

As documented in Figure 3, across various measures commonly used in the law literature, we find consistent evidence that the judicial reform has not only made court rulings less favourable toward local defendants, but also led to significant improvements in the quality of judicial decisions: (a) appeal rates decreased for external plaintiffs, while remaining unchanged for local defendants; (b) judges became more likely to approve requests for evidence examination and expert witness testimony; (c) court verdicts provided more detailed judicial reasoning in judgment files (with higher word counts); and (d) judges became less likely to cite discretionary codes in judicial reasoning. These results rule out the alternative interpretation that judicial reform did not actually lead to better judicial decisions, but instead simply enabled judges to start ``selling" judicial decisions equally to both sides.

Figure 3: Judicial organisational reform and judicial quality

Notes: In Panel (a), we plot the event study estimates for the appeal rate separately for the local defendants and external plaintiffs. In Panel (b), we plot the event study estimates for approval rate for evidence examination requests separately for the local defendants and external plaintiffs. In Panel (c), we plot the event study estimates for the word count for judicial reasoning in court verdicts. In Panel (d), we plot the event study estimates for the frequency of citing discretionary codes in judicial reasoning. All event studies are estimated following the approach suggested by Sun and Abraham (2021).

It is important to note that the judicial reform does not fully shield judicial decisions from political influence; instead, it consolidates judicial control to the higher levels of government. In the paper, we investigate the reform's limitations. Specifically, we examine whether the reform (a) led to more protection for firms connected to the provincial or central government; (b) failed to prevent protectionism in inter-provincial lawsuits; (c) was undermined in regions where the local officials were able to lobby the provincial government; (d) led to the promotion of less capable judges; (e) induced longer delays in rulings; or (f) reduced the rate of compliance with court orders. As discussed in greater detail in the paper, we find some evidence for (b), (c), and (d), while no evidence for (a), (e), and (f). Taking stock, our analysis suggests that, overall, the reform, while suffering from several potential limitations, has significantly reduced the scope for local court capture, and hence alleviated the extent of judicial local protectionism.

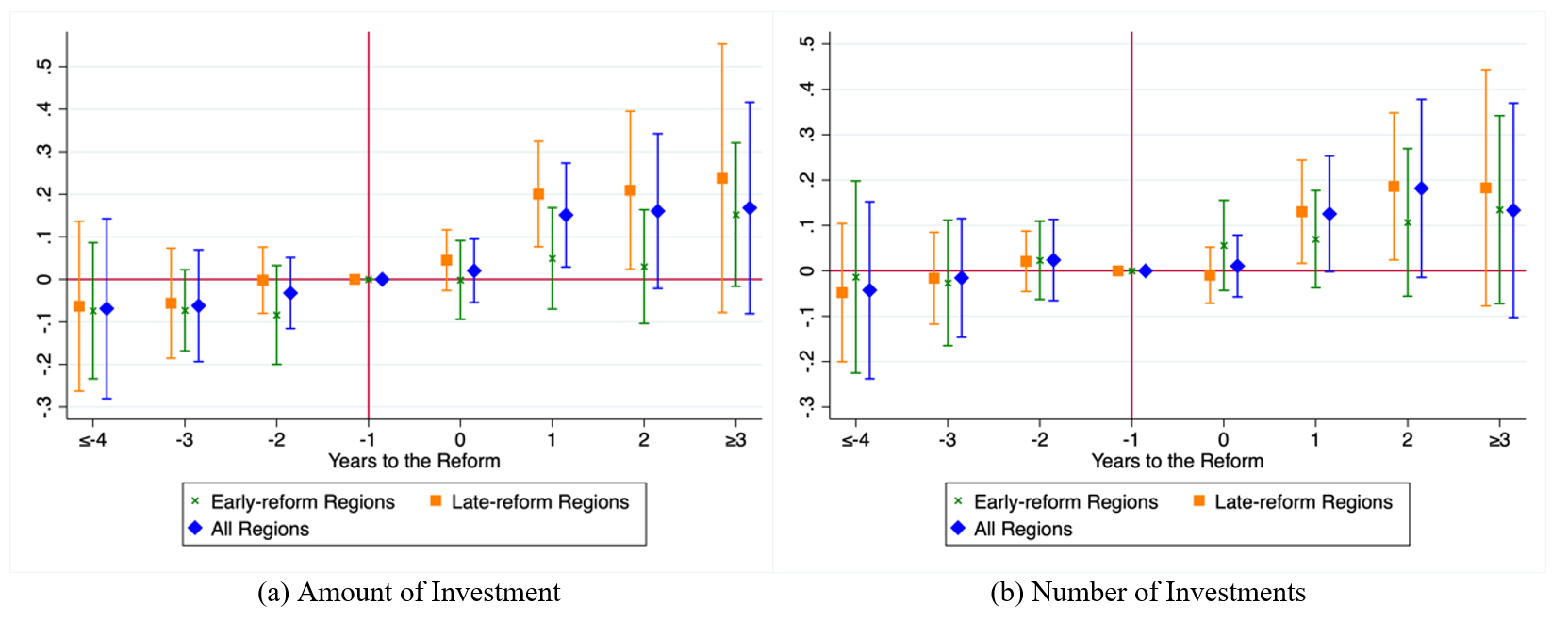

To understand how this affected economic integration, we construct a novel measure of cross-location entrepreneurial investment network in China by tracking the yearly changes in each firm's shareholding structure, as documented in the administrative business registration records. As shown in Figure 4, we find that, when a local court has undergone the judicial organisational reform, the number of inward investments from non-local business investors to local firms increased by 11.4%, while the total amount increased by 11.2%. The impact is significantly more pronounced in regions that implemented the reform in later years, whereas it is relatively modest in regions that embraced the reform earlier. This aligns with a scenario in which, as the reform extends across the nation, external investors progressively update their expectations regarding its effectiveness and adjust their investment decisions accordingly. These findings suggest that, the judicial organisational reform, by improving local business environments for non-local investors, has played important roles in facilitating economic integration in China. Using a model-based sufficient statistic, we calculate that, by fostering better economic integration, the judicial reform has the potential to increase China’s GDP by 1.9% in the long term.

Figure 4: Judicial organisational reform and external investment

Notes: Panel (a) plots the event study coefficients (as well as 95% confidence intervals) for the total amount of inward investment flows using samples of early-reform regions, late-reform regions, and the full sample, respectively. Panel (b) repeats the exercises using the number of inward investments as the outcome variable. All event studies are estimated following the approach suggested by Sun and Abraham (2021).

This systematic turn towards legalism at the local level despite political centralisation is an important yet under-appreciated change in China's delicate politico-economic equilibrium. Going forward, important questions remain on the sustainability of the co-existence between a centralised authoritarian government and independent local judiciaries, whether the movement towards legalism can progress further, and how the turn toward legalism will affect the fate of an authoritarian regime and the welfare of its citizens in the long run. Answering such questions will help us better understand China, as well as other authoritarian regimes worldwide, such as Pakistan, Russia, and Turkey, that have recently gone through similar judicial reforms.

References

Acemoglu, D and J A Robinson (2012), “Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty,” Currency.

Besley, T and T Persson (2011), “Pillars of prosperity,” Princeton University Press.

Buchanan, J M (1974), “Good economics-bad law,” Va. L. Rev., 60: 483.

Chen, H (2018), “"Ren Cai Wu Sheng Ji Tong Guan Gai Ge De Cheng Xiao Yu Wan Shan” Ren Min Fa Zhi, (Z1): 9–11.

China Supreme People’s Court (2019), “Zhong Guo Fa Yuan Si Fa Gai Ge: 2013-2020,” People’s Court Press.

Cooter, R D (1996), “Decentralized law for a complex economy: the structural approach to adjudicating the new law merchant,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 144(5): 1643–1696.

Djankov, S, R La Porta, F Lopez de Silanes, and A Shleifer (2003), “Courts,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2): 453–517.

Glaeser, E L and A Shleifer (2002), “Legal origins,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4): 1193–1229.

Gong, T (2004), “Dependent judiciary and unaccountable judges: Judicial corruption in contemporary China,” China Review: 33–54.

Hamilton, A (1788), “The judiciary department,” The Federalist, 78: 14.

Hay, J R and A Shleifer (1998), “Private enforcement of public laws: A theory of legal reform,” The American Economic Review, 88(2): 398–403.

Hayek, F A (1960), “The constitution of liberty: The definitive edition,” Routledge.

Li, L (2012), “The “production” of corruption in China’s courts: judicial politics and decision making in a one-party state,” Law & Social Inquiry, 37(4): 848–877.

Liu, E, Y Lu, W Peng, and S Wang (2023), “Court Capture, Local Protectionism, and Economic Integration: Evidence from China,” National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w30432.

Ng, K H and X He (2017), “Embedded courts: Judicial decision-making in China,” Cambridge University Press.

North, D C (1986), “The new institutional economics,” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (jite)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 142(1): 230–237.

Porta, R La, F Lopez de Silanes, and A Shleifer (2008), “The economic consequences of legal origins,” Journal of economic literature, 46(2): 285–332.

Porta, R La, C Pop-Eleches, and A Shleifer (2004), “Judicial checks and balances,” Journal of Political Economy, 112(2): 445–470.

Smith, A (1937), “The wealth of nations [1776],” Vol. 11937, na.

Sun, L and S Abraham (2021), “Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects,” Journal of Econometrics, 225(2): 175–199.

Wang, Y (2018), “Relative capture: quasi-experimental evidence from the Chinese judiciary,” Comparative Political Studies, 51(8): 1012–1041.

Xu, C (2011), “The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development,” Journal of economic literature, 49(4): 1076–1151.

Zhou, Q (2017), “Guanyu Renmin Fayuan Quanmian Shenhua Sifa Gaige De Baogao.”

Zhang, T and T Ginsburg (2019), “China’s turn toward law,” Va. J. Int’l L., 59: 306.