Progressive wealth taxes may be difficult to enforce if wealthy individuals underreport their wealth, but disclosure incentives and greater enforcement can improve tax collection

Developed countries have recently begun considering wealth taxes to raise revenue and curb rising inequality. Should developing countries follow suit? On the one hand, developing countries are often afflicted by acute income and wealth inequality (Alvaredo et al. 2018), and could thus benefit from a more progressive tax system. On the other hand, the question remains whether governments can enforce wealth taxes on an elite that have a vast arsenal of tools to evade taxes altogether.

Behavioural responses to wealth taxes and wealth tax Enforcement: Evidence from Colombia

My job market paper with Javier Ávila-Mahecha (Londoño-Vélez and Avila-Mahecha 2018) explores individual responses to personal wealth taxes and wealth tax enforcement in Colombia. Colombia provides a unique opportunity to study these issues thanks to its extensive administrative tax microdata on the assets and debts of wealthy individuals, and its numerous tax and enforcement policy changes since 2002.

Our data covers all income and wealth tax filers between 1993 and 2016. To observe offshore sheltering in Colombia’s most relevant tax havens, we match our tax records with the microdata from the Panama Papers – the information leaked from Mossack Fonseca, one of the world’s five largest wholesalers of offshore secrecy at the time of the leak.

The impact of wealth taxation on wealth reporting

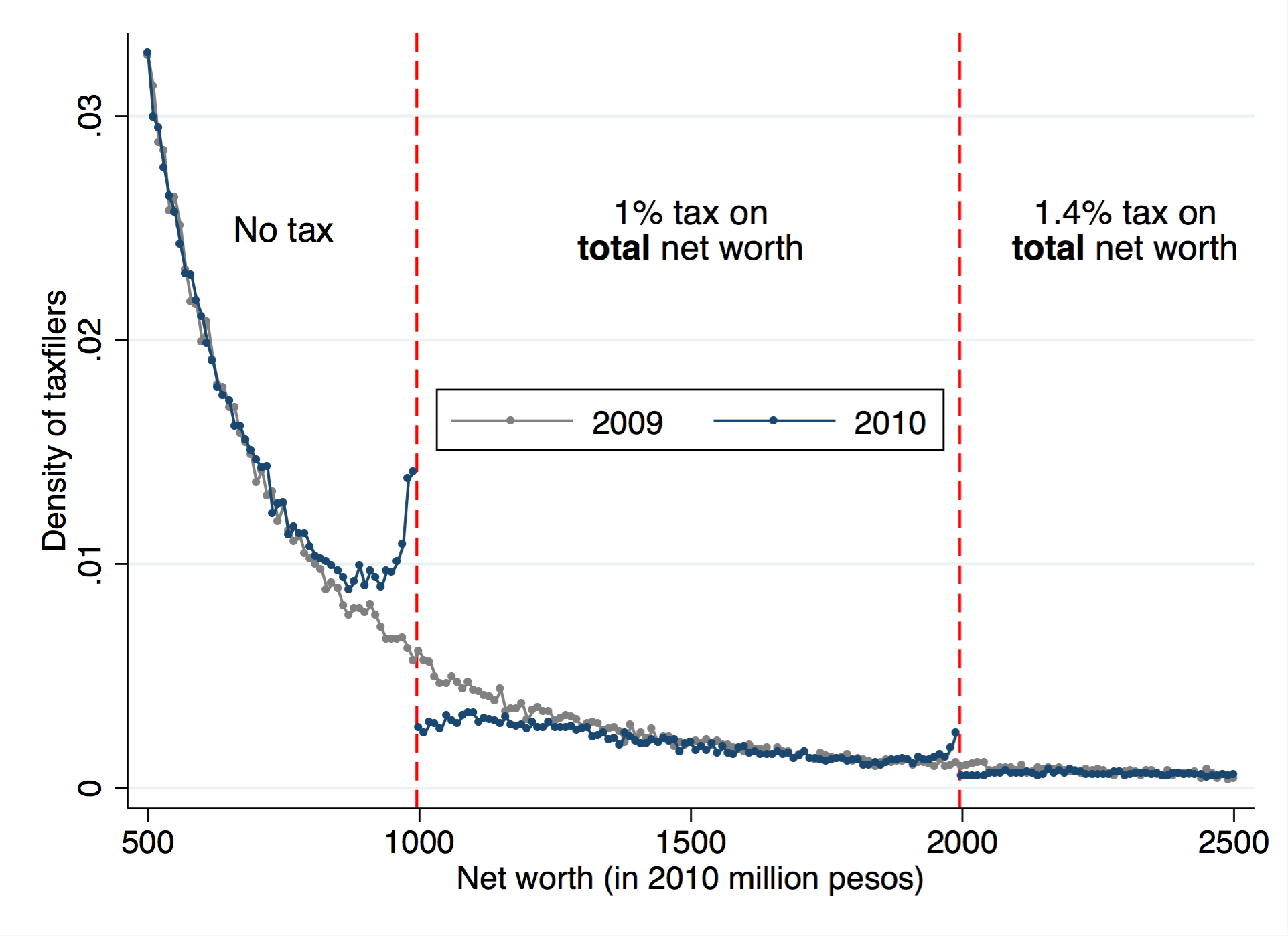

We first study responses to wealth taxes, exploiting quasi-experimental variation introduced by tax reforms in 2010 and discontinuities in the wealth tax schedule. The schedule assigned each bracket of net worth an average tax rate, creating jumps in tax liability at bracket cut-offs. For instance, in 2010, a taxpayer reporting 999.999 million pesos ($520,830) in wealth was exempt from the wealth tax, while a taxpayer reporting an additional peso owed 1% of all taxable net wealth (a tax bill of 10 million pesos, or $5,208). If individuals did not respond to the wealth tax, reported wealth would be distributed smoothly around this bracket cut-off. If, instead, individuals avoided the jump in tax liability, there would be bunching in reported wealth below it. Accordingly, the degree of bunching indicates the responsiveness of reported wealth to the tax ( Saez 2010, Kleven and Waseem 2013).

The findings: Underreporting and offshoring

We find large and immediate responses to wealth taxation, providing clear evidence that wealthy individuals respond to the incentives created by tax policy (see Figure 1). In our main analysis, the marginal ‘buncher’ would have reported 21% more wealth in the absence of the wealth tax. Our estimated elasticity suggests that a 1% increase in (one minus) the wealth tax rate raises reported wealth by 2%. These responses generate revenue losses of up to one-fifth of the mechanical projected revenue.

Figure 1 Distribution of reported wealth in 2009 (pre-reform) and 2010 (post-reform)

Unlike earnings responses to income taxes, which potentially conflate real and sheltering responses, bunching in the distribution of reported wealth predominantly reflects sheltering. It is difficult for individuals to immediately bunch below the notch points using real responses (e.g. investment) because wealth – a stock – partly depends on asset prices, which are uncertain and fluctuate throughout the year (Jakobsen et al. 2018). Furthermore, in Colombia there has been limited systematic crosschecking of items reported in the wealth tax return using third-party reported information. This enabled individuals to avoid taxes, as we show, by underreporting the value of assets not subject to third-party reporting and fabricating debt.

In addition, wealthy individuals often have access to sophisticated tax sheltering strategies and may reduce their tax burden by offshoring assets to tax havens. Illustrating this point, the Panama Papers reveal offshore entities are used predominantly by very wealthy Colombians. The wealthiest 0.01% of the distribution are 24 times more likely to be named in the leak than the wealthiest 5%.

These offshore entities were used at least in part to hide assets from the tax authority. While Colombia requires taxpayers to report all domestic and foreign assets, the value of reported assets significantly drops immediately after an individual incorporates an offshore entity. These offshore entities have been used more aggressively since the reintroduction of wealth taxation in Colombia.

Tax evasion responds to enforcement: A voluntary disclosure scheme

Can better enforcement crack down on offshore evasion and recover tax on hidden wealth?

Between 2015 and 2017, Colombia carried out a series of enforcement initiatives to improve compliance among wealthy taxpayers. Similar to voluntary disclosure schemes implemented in the US and other OECD countries, Colombia awarded tax incentives for disclosing unreported (foreign and domestic) assets and non-existent debts. Disclosers waived past income and wealth tax liabilities but paid a penalty, while evaders who did not come forward faced higher fines if caught cheating.

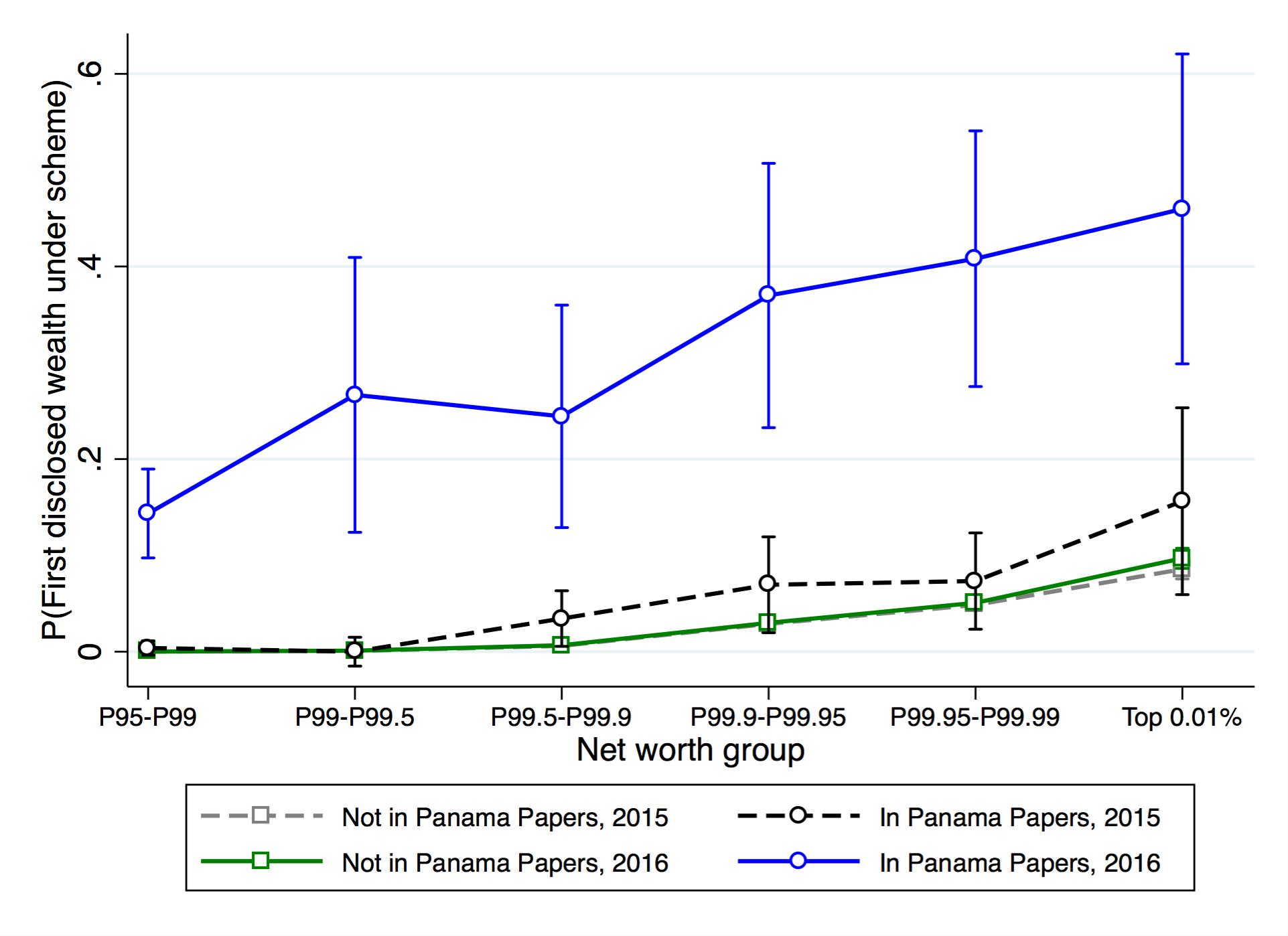

Colombia’s programme encouraged disclosures worth more than 1.7% of GDP. Evaders who disclosed under the scheme are among the wealthiest individuals in the country – two-fifths of individuals in the wealthiest 0.01% admitted to prior noncompliance and disclosed hidden wealth. Disclosing under the scheme rises starkly with wealth – individuals in the top 0.01% are 55 times as likely to disclose than those in the top 5% overall. Most wealth had been hidden abroad, reflecting the pervasiveness of offshore tax evasion at the top of the distribution.

The scheme improved income and wealth tax compliance for the wealthiest taxpayers. Relative to individuals who did not disclose under the scheme, disclosers reported more wealth as well as more capital income from asset ownership three years after their first admission of noncompliance. As a result, they also paid 39% more income taxes relative to non-disclosers, further enhancing tax progressivity in the longer term.

1. Tax evasion also responds to the risk of detection: The Panama Papers leak

Halfway through the disclosure scheme, the Panama Papers news story broke and the names of Mossack Fonseca’s clients were thrust into the public spotlight. The Colombian tax authority reacted by scrutinising Mossack Fonseca and its clients, contacting taxpayers named in the leak and requesting documentation of their offshore activities and transactions. Three weeks later, the governments of Colombia and Panama announced a tax information exchange agreement between the two countries – a move the tax haven had resisted for years.

The exogenous timing of the leak enables identifying how whistleblowing directly contributes to tax compliance among wealthy individuals. We compare outcomes between wealth tax filers named (treated) and not named (control) in the leak before and after it occurred. We find that the Panama Papers leak and subsequent events induced a more than 800% increase in disclosures under the scheme (Figure 2) and a more than fifteenfold rise in disclosures of foreign assets in particular. Consequently, taxes owed by these individuals more than doubled.

Figure 2 The Panama Papers leak raised disclosures of hidden wealth

2. Tougher sanctions for noncompliance might improve compliance

Six months later, Colombia criminalised tax evasion for the first time. If convicted, tax evaders could face up to nine years in prison. We find that most participants disclosed hidden wealth after this event, arguably at least in part due to the harsher punishment of tax evasion.

Implications: Greater enforcement improves wealth tax collection

- Wider coverage of third-party reporting, if coupled with systematic cross-validation of reported information and increased scrutiny of high net worth taxpayers, can strengthen enforcement capacity in developing countries.

- Policies to promote financial transparency and encourage foreign asset reporting are key to curb offshore sheltering at the top of the wealth distribution.

- Voluntary disclosure schemes may help collect new information about offshore assets and income and generate more revenue from wealthy taxpayers. For such programmes to be effective in improving compliance in the shorter and longer term, stricter enforcement needs tough noncompliance sanctions and a credible threat of detection. For example, by exploiting the automatic exchange of tax information and whistle-blower data.

With better enforcement, wealth taxes can complement progressive income taxes to reinforce tax progressivity, even in contexts where elites are difficult to tax.

References

Alvaredo, F and J Londoño-Vélez (2014), “Altos ingresos e impuesto de renta en Colombia, 1993 - 2010”, Revista de Economia Institucional 16(31): 157–194.

Jakobsen, K, K Jakobsen, H Kleven and G Zucman (2018), “Wealth Taxation and Wealth Accumulation: Theory and Evidence from Denmark”, NBER Working Paper No. 24371.

Kleven, H and M Waseem (2013), “Using notches to uncover optimization frictions and structural elasticities: Theory and evidence from Pakistan”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(2): 669– 723.

Londoño-Vélez, J and J Avila-Mahecha (2018), “Can Wealth Taxation Work in Developing Countries? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Colombia”, Job Market Paper.

Saez, E (2010), “Do taxpayers bunch at kink points?”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2(3): 180–212.