How does information about tax audits affect tax evasion? Firms do increase their tax compliance but this response is not necessarily rational.

Tax evasion is rampant in developing countries and poses a huge challenge for policymakers. In Latin America, for example, the evasion rate for value added taxes (VAT), which comprises a significant proportion of tax revenues, is around 26% (ECLAC 2016). More efficient tax collection can translate into welfare gains (Slemrod 2017). Additionally, higher tax compliance would allow governments to finance growth-promoting expenditures in education and health.

In order to design effective tax enforcement, we need to understand how individuals and firms make evasion decisions. The canonical public finance model from Allingham and Sandmo (henceforth, “A&S”) suggests that tax evasion decisions follow a cost-benefit analysis: individuals weigh the expected benefit from hiding income from the tax agency against the potential unearthing of evasion via tax audits and the penalties imposed thereupon (Allingham and Sandmo 1972). Tax audits may be inconsequential in certain contexts. For instance, due to automatic third-party reporting, it is normally a bad idea to under-report wage income (Kleven et al. 2011). For some entities, however, such as self-employed individuals reporting income taxes or firms reporting VAT, the optimal evasion rate boils down to characteristics of tax audits, such as the probability of being audited and the penalty rates for evasion. We conducted a field experiment in collaboration with the tax agency in Uruguay to examine how firms react to the potential threat of tax audits when they learn about these characteristics (Bergolo et al. 2017).

Context and study design

This is a high-stakes context: the average firm in our experiment paid US$7,700 in VAT, as well as $4,070 in other taxes. Total tax revenue in Uruguay represents 19% of GDP, half of which is collected through VAT. This is also a context in which firms had sufficient time to learn about how to optimise their tax reporting (the average firm in our sample had been paying taxes for the last 14 years). We sent letters to the owners of around 20,000 medium and small firms, that collectively pay over $200 million in taxes per year, and randomly assigned what information would be included in the letters. The following were two of the primary treatment arms:

- A baseline letter included some generic information about the tax agency.

- An audit-statistics letter contained the same information as the baseline letter plus an additional paragraph about the average probability of being audited and the average penalty rate.

The study examined the effect of the information contained in these letters on two different outcomes, using two types of data:

- We used administrative data from the tax agency to look at how the information affected the behaviour of these firms, including their monthly tax payments.

- We used survey data, collected nine months after the letters were sent, to measure the effects of the information on beliefs such as the perceived audit probability and the perceived penalty rate.

Our results: Information about audit probabilities and penalty rates increased tax payments

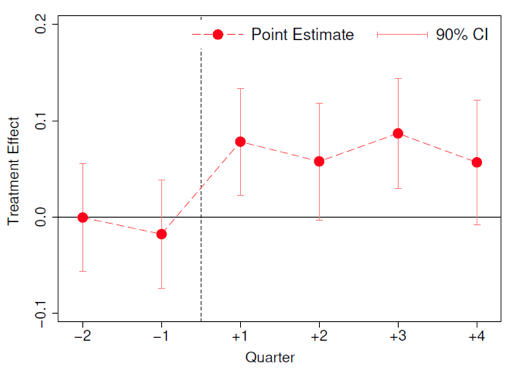

By comparing the outcomes of firms who received the baseline letters to firms who received the audit-statistics letters, we are able to disentangle and precisely measure the effects of providing firms with accurate information about the audit probabilities and penalty rates. Figure 1 shows an event-study analysis of these experimental effects. The vertical dashed line denotes when the letters were delivered to the owners of the firm. In the two quarters (-2 and -1) prior to delivery of letters, VAT payments were roughly the same between the two treatment arms. However, right after letter delivery, recipients of the audit-statistics group began paying significantly more in taxes than recipients of the baseline group.

Figure 1 Difference in tax payments, audit-statistics vs baseline letters

Notes: N=12,336. The vertical (dashed) line denotes the date on which the letters were delivered. Each red circle corresponds to a Poisson regression for a different quarter. Confidence intervals, represented by red lines, are computed with heteroskedastic-robust standard errors.

These results suggest that the information about audits increased tax payments by about 6.3%. This effect is not only statistically significant, but also economically substantial: according to independent estimates, it amounts to a 24% reduction in the average VAT evasion rate. Our findings are consistent with prior experimental evidence. For instance, in a seminal contribution, Slemrod et al. (2001) showed that, for a sample of US self-employed individuals, those who were randomly assigned to receive a letter from the Internal Revenue Services (IRS) with an enforcement message reported higher incomes in their tax returns. Similar reminders about tax enforcement have been shown to have positive effects on compliance in a variety of other contexts (e.g. Pomeranz 2015 for the case of VAT in Chile).

Mechanism tests: Evidence contradicts the A&S model’s predictions

Why do firms react to information about audits? The A&S model provides a potential explanation: the information provided affects their beliefs about the auditing process, and firms alter their evasion as a way of re-optimising under these new beliefs, as any rational agent would do. Our research design provides two tests of this mechanism:

- The first test leverages the survey data. According to the A&S model, if firms increased their tax payments, the information sent to them must have increased their perceptions about the probability of being audited, or the penalty rates. We find that, on the contrary, the audit information decreased the average perception of the probability of an audit.

- The second test leverages sub-treatments of the audit-statistics letter. When we computed the average audit probability and penalty rate to be included in the audit-statistics message, we drew from different samples of firms for different letter recipients. This introduced substantial sampling variation in the information shown to the recipients: a firm could be told that the probability of an audit was, say, 8%, 10%, or 15%, depending on the sample of firms that was drawn for that particular letter. The A&S model predicts that firms that were randomly shown higher audit probabilities and higher penalty rates should evade less. We find, however, that the average elasticities of tax compliance with respect to audit probability and penalty rate are close to zero and precisely estimated. The results are similar under a different treatment arm – the audit-threat letter – in which, instead of creating random variation in the statistics shown to the respondents, we randomly assigned the actual audit probabilities to which the respondents were going to be subjected to.

The scarecrow analogy: Rationality versus fear

In sum, our findings constitute suggestive evidence that tax audits may matter, but not necessarily because firms are making a calculated cost-benefit analysis, as in the A&S model and alluded to above. A plausible explanation for this counterintuitive evidence is that it is possible firms react to information about audits in the way they do because it triggers an irrational fear – that is, tax audits may scare firms into paying their taxes in the same way that scarecrows frighten off birds.

Policy implications

Our findings may also have direct policy implications. In the traditional framework, a tax agency’s aim is to find the optimal audit probability. Our findings suggest that, holding the actual audit probability fixed, tax agencies may influence tax compliance by simply choosing how to communicate this information to taxpayers. Indeed, there is some evidence that tax agencies are already taking advantage of this approach. For instance, Blank and Levin (2010) find a disproportionately large number of tax enforcement press releases during the weeks immediately prior to Tax Day in the US, presumably in order to scare taxpayers while they are preparing to file their annual tax returns.

References

Allingham, M G and Sandmo, A (1972), “Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis”, Journal of Public Economics 1: 323-338.

Bergolo, M, Ceni, R, Cruces, G, Giaccobasso, M and Perez-Truglia, R (2017), “Tax Audits as Scarecrows: Evidence from a Large Field Experiment”, NBER Working Paper No. 23631.

Blank, J D and Levin, D Z (2010), “When is Tax Enforcement Publicized?”, Virginia Tax Review 30(1), 15-18.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) (2016), “Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2016".

Kleven, H, Knudsen, M, Kreiner, C, Pedersen, S and Saez, E (2011), “Unwilling or Unable to Cheat? Evidence from a Tax Audit Experiment in Denmark”, Econometrica 79, 651-692.

Pomeranz, D (2015), “No Taxation Without Information: Deterrence and Self-Enforcement in the Value Added Tax”, American Economic Review 105(8), 2539-2569.

Slemrod, J, Blumenthal, M and Christian C (2001), “Taxpayer Response to an Increased Probability of Audit: Evidence from a Controlled Experiment in Minnesota”, Journal of Public Economics 79 (3):455-483.

Slemrod, J (2017), “Tax Compliance and Enforcement”, Journal of Economic Literature, forthcoming.