Firms used VAT savings from China’s tax reform to invest in machinery as intended, but the reform reduced firm productivity, exports and employment

Beginning in 2004, the Chinese government implemented value-added tax (VAT) reform in three northeastern provinces, which eliminated double taxation on investments in machinery. The objective of reform was to encourage firms to raise investment spending on fixed assets for production (excluding structures) and to upgrade their machinery and equipment.

In 2009, this tax reform was extended to the whole country. The goals were similar, but in addition the government sought to help firms weather the adverse effects of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. The tax reform was also part of an industrial policy that focused on promoting more technologically advanced sectors.

Tax revenue in China

VAT is the major source of fiscal revenue for the Chinese government, generating much more revenue than any other type of tax. In 2002, revenue from the VAT was 814.4 billion renminbi, accounting for around 48% of the total state tax revenue. In 2009, the Chinese Ministry of Finance estimated that VAT revenue accounted for approximately 31% of China’s overall revenue.

Prior to 2004, China had a production-based VAT, and purchases of fixed investments could not be deducted from sales when calculating VAT liabilities. Consequently, investment goods were taxed twice – first when firms purchased the goods, and again when consumers purchased the final product that had been produced using the investment goods as intermediate inputs.

Concerns were raised that such double taxation could increase the cost of investment, leading firms to operate with old equipment and out-of-date technology, leading to lower productivity growth.

Impact of the reform: Tax, investment, and growth

The 2004 VAT reform eliminated double taxation and alleviated firms’ tax burden. Because the reform reduced the cost of physical investment, treated firms were expected to increase investment by upgrading machinery and to improve productivity. Because of the substitution between labour and capital, the reform — which lowered the cost of physical investment — was also expected to reduce the demand for labour.

The 2004 VAT reform was implemented in three northeastern provinces (Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang) and six industries (agricultural product processing, equipment manufacturing, petrochemicals, metallurgy, ship building, and automobile manufacturing).

Comparing development indicators between the treated and control provinces before 2004, we find that there were no significant differences in GDP, government revenue, VAT revenue, investment, number of firms, or fixed assets between treated and control regions prior to the reform.

Despite anecdotal evidence suggesting that the treated regions are typically considered backward, our evidence indicates that the firms we examined in the treated and control regions were reasonably similar.

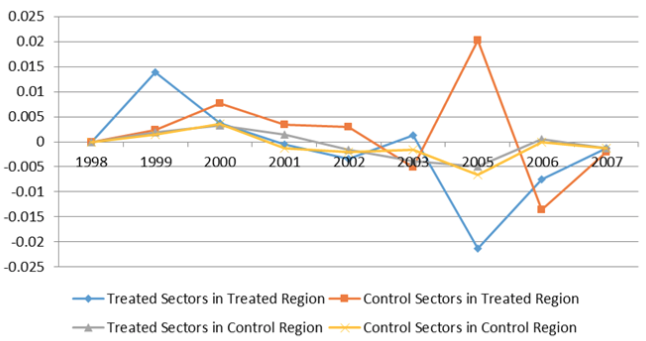

Figure 1 Evolution of the annual growth of value-added tax: All sectors sample

The policy change is evident from the trends in Figure 1, which shows the growth of VAT in treated and control groups from 1998 to 2007. The VAT rate is defined as the VAT paid divided by value-added at the firm level. We do not include 2004 in the figure because the variable value added is missing for that year in the NBS data.

Figure 1 shows that over the sample period, the VAT rate paid by firms in control sectors in control provinces did not change much and growth rates were essentially zero before and after the 2004 reform. However, one year after the VAT reform was implemented in 2004, there was a significant decrease of 2 percentage points in the growth of the VAT paid by treated firms, and the tax paid by treated firms continued to fall until 2007.

Looking at firms in the control sectors of treated regions, there was a jump in the VAT paid by those firms in 2005, but it fell afterwards. The evidence in Figure 1 shows essentially no change in VAT for both the treatment and control sectors in the control provinces, but significant reductions in the VAT rate for treatment sectors in treated provinces between 2003 and 2005.

The study: Accessing the effectiveness of the 2004 VAT reform

In Cai and Harrison (2018), we use a firm-level panel dataset covering 1998 through 2007 to identify the effect of the 2004 VAT reduction in selected provinces on the behaviour of manufacturing firms. Our measures of firm outcomes are broad and include investment, the share of new products in sales, productivity, employment, and exports. This reform is easy to study because we know exactly which provinces and sectors were targeted first, and consequently, we have a clean treatment group as well as a control group.

The findings: VAT, capital, employment, investment, growth, new products, and exports

All our statistical approaches suggest that the reform was effective in reducing the incidence of VAT paid by firms, with VAT falling one to two percentage points in the treatment areas relative to the non-treatment areas. The statutory rate for the VAT is 17%, so the reduction in VAT paid in treatment areas accounts for a reduction in the statutory rate of between 6% and 12%.

We also explore the consequences for employment, investment, and other outcomes. The reform encouraged firms to substitute physical capital for labour: The policy significantly reduced firm total employment across all ownership types. The net impact of the reform was to increase the capital intensity of production, defined as the labour to capital ratio.

As the reform focused on machinery and excluded physical structures from the VAT exemption, not surprisingly, we find that the composition of investment shifted towards machinery. However, the aggregate amount of investment did not increase.

We also explore the impact on new product introductions, exports, and productivity growth. We find a reduction in new product introductions after the reform. The reform also negatively and significantly affected firm productivity and significantly decreased export intensity for most types of firms.

Implications: Favouring physical investments and capital-intensive technologies

The negative effects of the reform on productivity growth, new product introductions, and exporting is consistent with our theoretical model showing that the reform led firms to favour physical investments over human capital or intellectual capital investments. In addition, the reform encouraged firms to choose capital-intensive technologies, which may not have been consistent with China’s comparative advantage, at least during our sample period.

Our evidence suggests that the primary effects of the tax reform over the three-year period following the policy changes were to reduce VAT payments, increase machinery investment relative to other types of investment, and cut employment. Firms also shifted to more capital-intensive or labour-saving technologies.

Two mechanisms to explain the unintended consequences of reform

1. The VAT reform had heterogeneous effects depending on the extent to which firms were constrained prior to the reform.

For firms with hypothetically big savings from the reduced VAT, we see large increases in the share of investment in machinery.

We also show that the negative impacts of the VAT reform are concentrated in firms that already had access to cheap capital. The expected effects of lower VAT payments in stimulating investment were concentrated in firms facing higher interest rates, suggesting that the reform only promoted investment for capital-constrained enterprises.

2. The VAT reform led to significant declines in revenues for implementing regions.

We show that this is the case by measuring the impact of the VAT reform on other industrial policies used by policymakers in these regions. The VAT reform is associated with a significantly lower incidence of subsidies, tax holidays, and low interest loans. We also find a significant decline in firm profits for domestically owned private enterprises.

The fact that treated firms received less support from other government programmes after the treatment contributed to the observed fall in exports and new product sales. Our main focus is the net impact of the reform, taking into account its opposite consequences for investment and for other industrial policies that were financed by VAT revenues.

Why was the reform extended?

Why was the reform extended to the rest of China given that the benefits of the reform, in terms of increasing aggregate investment and even productive investment, seem quite limited and targeted at state-owned enterprises? One likely explanation is that extending this reform was part of a comprehensive stimulus package in response to the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

Editors' note: This is an adapted version of the blog, "Industrial Policy in China: Some Intended or Unintended Consequences?", first published by VoxChina. This is part of our blog series on industrial policy.

References

Aghion, P, J Cai, M Dewatripont, A Harrison and P Legros (2015), “Industrial Policy and Competition”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7(4): 1-32.

Boeing, P (2016), “The Allocation and Effectiveness of China’s R&D Subsidies— Evidence from Listed Firms”, Research Policy 45(9): 1774- 1789.

Griffith, R, H Miller and M O’Connell (2014), “Ownership of Intellectual Property and Corporate Taxation”, Journal of Public Economics 112:12-23.

Harrison, A and A Cai (2018), “Industrial Policy in China: Some Intended or Unintended Consequences?”, Working Paper.

Hassett, K and G Hubbard (2002), “Tax Policy and Business Investment”, in Handbook of Public Economics, pp. 1293- 1343.

Liu, Q and Y Lu (2015), “Firm Investment and Exporting: Evidence from China’s Value-Added Tax Reform”, Journal of International Economics 97(2): 392- 403.