Economic complexity and R&D investment influence the number, size, product quality, and diversification of exporters, making them policy priorities

Productive and technological capabilities are an essential engine for export growth, economic growth, and development. Early development pioneers emphasised that the process of absorbing, learning, combining, and creating knowledge drives the transformation of economic structures from agriculture and extractive industries to more sophisticated activities (Hirschman 1958).

Schumpeter underlined the importance of innovation activities and research and development (R&D) investments, while modern growth theories highlighted the role of human capital and, more broadly, knowledge, as a major driver of growth.

Drivers of growth: Innovation, capabilities, and exports

Recent experiences from East Asian economies illustrate how the accumulation of capabilities contributed to catching-up in living standards relative to more advanced economies (Cimoli et al. 2009). By contrast, Latin American and African countries have performed poorly, lagging in their technological development and productivity growth (McMillan et al. 2017, Grazzi and Petrobelli 2016). International competitiveness and the development outlook in these regions remain fragile and highly dependent on the fluctuations of commodity prices.

There is also a plethora of studies illustrating the connection between technological capabilities and export performance at the firm level. Innovation activities and capabilities accumulation – including product design, production processes, management routines, and marketing – are critical to fostering export growth and for expanding developing countries’ market share. Interestingly, firms’ export decisions seem to be intimately related to investment, technology adoption, product-mix, and innovation choices (Aw et al. 2011).

Despite these theoretical and empirical advances, there are still many open questions on how capabilities influence export performance and dynamics across developing countries. For example, the average steel exporter in Turkey is 1.5 times larger than the average steel exporter in Mexico. Bangladesh exporters of apparel and clothing accessories export to more than four destinations on average, while in Pakistan, they export to only two destinations each.

The average Mexican exporter of electrical machinery and equipment exports on average more than six different products, while Thai exporters export only four products. These differences are related to the size of the country, level of development, trade policy, and comparative advantages. What is the role of productive and technological capabilities?

Capabilities in the developing world: Economic complexity and R&D investment

There are several measures that capture distinctive aspects of capabilities across countries. In recent years, the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) has gained prominence to measure productive capacities (Hausman et al. 2011). The ECI measures the multiplicity of productive knowledge embedded in an economy by combining information on the diversity of a country’s exports and the ubiquity of its products.

Technological capabilities are traditionally proxied by R&D investments, which reflect the level of effort that countries spend to foster knowledge creation and absorption. In fact, a firm’s R&D activities not only encourage product and process innovations, but also enhance their capacity to assimilate external knowledge.

Figure 1 displays the ECI and R&D investments across developing countries. Despite the positive correlation, the dispersion underscores that the ECI and R&D investments reflect distinctive aspects of capabilities.

For example, Mexico displays a relatively high ECI as its export structure is relatively diversified, with a large share of medium-high and high-technology products, as a result of the significant presence of transnational firms. However, technological efforts are limited, with relatively low levels of R&D investments, illustrating the weaknesses in its national innovation system.

By contrast, Kenya exhibits a relatively low level of ECI, as its export structure is highly concentrated in a few agricultural products and textiles. Yet, Kenya has strengthened its efforts to increase R&D investments to about 0.8% of GDP, which is a relatively high figure for a developing country.

Meanwhile, China shows a robust performance regarding both indicators, with an export structure composed by a large share of high-technology products and R&D investments (about 2% of GDP), the highest among developing countries.

Figure 1 Economic complexity index and R&D investments

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from the World Development Indicators (WDI) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Observatory on Economic Complexity. Data is for 2015 or latest available year.

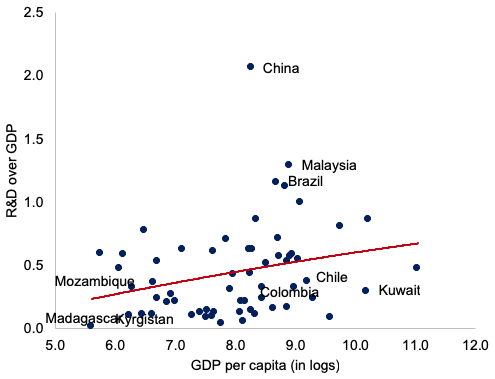

Figure 2 display the plots for ECI and R&D investments against the level of development. As expected, both are positively correlated with GDP per capita, but countries’ specific situations greatly differ. For example, countries such as Kuwait, Qatar, and Chile exhibit a low level of ECI, despite a relatively high level of GDP per capita.

Meanwhile, relatively poor countries tend to invest little in R&D, but there are also a variety of country specific circumstances. Countries like Colombia and some Arab States of the Persian Gulf display a relatively high GDP per capita among developing countries, but they underperform regarding R&D investments.

Figure 2 Capabilities and level of development

a) Economic Complexity Index

b) R&D Investments

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from World Development Indicators (WDI), World Bank, and the MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity. Accessible: https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/. Data is for 2015 or latest available year.

The findings: Capabilities and export dynamics

In analysing the role of productive and technological capabilities on export dynamics in developing countries, I exploit a country-sector-year database (Vergara 2018), which contains exporter-level statistical information (Fernandes et al. 2016). The objective is to link productive and technological capabilities – proxied by the ECI and R&D investments, respectively – with several merchandise export dimensions.

Do countries with more productive capacities have more and larger exporters? Do exporters from countries with more productive capacities charge higher prices for their products? Are exporters from countries with more technological capabilities more diversified in terms of products and destinations?

Interestingly, productive and technological capabilities are strongly connected to several export dimensions, even after controlling for level of development, trade openness, the size of the manufacturing sector, and commodity dependency. Countries with higher productive capacities have more exporters, in total and per product, and their exporters are larger. Also, these exporters charge higher prices for their products, which suggest a higher quality of their export products.

In addition, there is strong positive relationship between technological capabilities and diversification: Exporters in developing countries with stronger capabilities tend to export both a higher number of products and to more destination markets. This is a crucial factor for developing countries to better navigate trade shocks.

Finally, technological capabilities play a specific role in high-technology sectors, such as electronics, electrical machinery and equipment, and pharmaceuticals. In these sectors, exporters from countries with more R&D investments are more diversified in term of destination markets.

Three key implications

These findings entail important considerations:

- First, they explicitly underscore the asymmetries of technological capabilities among developing countries, and how they relate to many export dimensions. Thus, technological capabilities should be a key aspect in understanding the consequences from new trade policy environments. For example, the recent rise in trade protectionism in some countries or the African Continental Free Trade Agreement.

- Second, these results have implications not only on the countries’ resilience to trade shocks but also on their medium-term development prospects.

- Third, these findings are consistent with the view that the creation and expansion of technological capabilities through proactive policies are prior to the effect that incentives, such as trade liberalisation, might have on exports. In brief, countries must prioritise the creation and expansion of productive and technological capabilities for their own development prospects.

Author’s note: I am grateful to Helena Afonso for excellent comments and suggestions. The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations.

References

Aw, B Y, Roberts, M J and Yi Xu, D (2011), “R&D Investment, Exporting, and Productivity Dynamics”, American Economic Review 101(4): 1312–44.

Cimoli, M, Dosi, G and Stiglitz, J (2009), Industrial Policy and Development. The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation, Oxford University Press.

Fernandes, A M., Freund, C and Pierola, M D (2016), “Export Behavior, Country Size and Stage of Development: Evidence from the Exporter Dynamics Database”, Journal of Development Economics 119: 121-137.

Grazzi, M and Pietrobelli, C (2016), Firm Innovation and Productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean, the Engine of Economic Development, Inter-American Development Bank, Palgrave Macmillan.

Hausmann, R, Hidalgo, C A, Bustos, S, Coscia, M, Chung, S, Jimenez, J, Simoes, A and Yildirim, M A (2011). The Atlas of Economic Complexity. Mapping the path to Prosperity, Center for International Development at Harvard University and MIT Media Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hirschman, A O (1958). The Strategy of Economic Development, Vol. 10, Yale University Press.

McMillan, M, Rodrik, D and Verduzco-Gallo, I (2017). “Globalization, Structural Change, and Productivity Growth, with an Update on Africa”, World Development 63: 11-32.

Vergara, S (2018), "The Role of Productive and Technological Capabilities on Export Dynamics in Developing Countries", Working Paper.