An evaluation of two programmes reveals that public disclosure of tax information and social recognition of top taxpayers increases tax revenues

Raising insufficient revenues is a key factor stifling growth in emerging economies. Can public disclosure of tax payments and social recognition of top taxpayers help governments raise additional revenues? In a recent study (Slemrod et al. 2020), my co-authors and I examine two Pakistani programmes to answer this question.

Public disclosure of tax information

Pakistan began revealing income tax paid by every taxpayer in the country from 2012. Simultaneously, another programme began honouring the top 100 taxpayers in each of four categories — self-employed individuals, wage-earners, partnerships, and corporations.

Public disclosure of tax information can encourage whistle-blowing, evoke shame and guilt, or inspire pride. By being seen as fulfilling one’s civic duty or being seen as very affluent, social recognition of top taxpayers can similarly stimulate a sense of pride and self-fulfilment. Through these channels, the programmes can promote tax compliance (Luttmer and Singhal 2014).

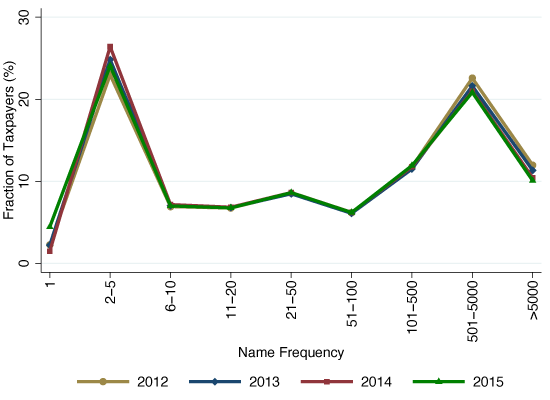

Under the public disclosure programme, the government publishes income tax paid along with full names of all taxpayers in a PDF document that is available online and can be downloaded freely. Figure 1 shows the distribution of full names among taxpayers listed in the disclosure.

Figure 1 Distribution of full names amongst taxpayers in Pakistan

There is wide variation in the extent to which a given name is shared by taxpayers. Around one-third of the names are extremely common, shared by more than 500 taxpayers. On the other hand, a similar proportion of taxpayers have unique or almost unique names.

Given that the full name is the sole information by which people can identify a taxpayer in the published information, the wide variation in the commonness of a name translates into a wide variation in the effectiveness of the disclosure. We exploit this variation to estimate the effect of the disclosure on tax payments. Figure 2 shows the headline result. The tax payments of individuals with less common names on average went up by nearly 10% as compared to those of the other taxpayers.

Figure 2 The effect of public disclosure on tax payments

Rewarding top taxpayers

The other programme we examine publicly recognises and rewards the top taxpayers of the country. Each year the top 100 taxpayers in each of the four categories are awarded a Taxpayers Honour & Privilege Card in a ceremony hosted by the prime minister. Holders of the card enjoy some privileges throughout the next year, which include invitations to state dinners, fast-track immigration, and gratis passports.

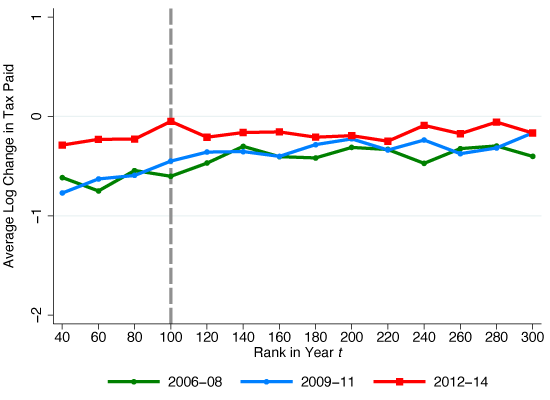

If the social recognition and other privileges afforded by the card are important, the tax payment of taxpayers ranked close to 100 would spike up as taxpayers below the cutoff try to become eligible for the programme and taxpayers just above the cutoff try to remain eligible.

We test this in a sample comprising the top 1,000 taxpayers of the four categories (see Figure 3). We indeed see such a spike. The tax payments of taxpayers ranked between 80 and 120 go up by nearly 18% compared to the other taxpayers as a result of the programme.

Figure 3 The effect of social recognition on tax payments

Conclusion: Social incentives and tax compliance

Tax evasion is pervasive in developing economies. Waseem (2019) estimates that low- and middle-income self-employed in Pakistan underreport their income by at least 70%. Similarly, nearly 38% of value added tax (VAT) base goes unreported in the country (Waseem 2020a, 2020b). Comparable levels of non-compliance are observed in other developing economies (Slemrod 2019).

Public disclosure of tax information and social recognition of top taxpayers cost little in terms of resources. The evidence we uncover shows that they can be important and cost-effective policy levers to mobilise additional resources, especially in countries with weak enforcement capacity.

References

Luttmer, E F P and M, Singhal. (2014), “Tax Morale”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(4): 149–168.

Slemrod, J (2019), “Tax compliance and enforcement”, Journal of Economic Literature 57(4): 904–54.

Slemrod, J, O U, Rehman, and M, Waseem (2020), "How Do Taxpayers Respond to Public Disclosure and Social Recognition Programs? Evidence from Pakistan", CEPR Discussion Paper 14463.

Waseem, M (2019), “Does Cutting the Tax Rate to Zero Induce Behavior Different from Other Tax Cuts? Evidence from Pakistan”, Review of Economics & Statistics (forthcoming).

Waseem, M (2020a), "The Role of Withholding in the Self-Enforcement of a Value-Added Tax: Evidence from Pakistan", CESifo Working Paper.

Waseem, M (2020b), "Overclaimed Refunds, Undeclared Sales, and Invoice Mills: Nature and Extent of Noncompliance in a Value-Added Tax", Working Paper.