Representation in child media matters. Sesame Street’s positive representations of minorities and working women in 1969 had long run impacts on prejudices, influencing people’s propensity to vote for diverse candidates decades later.

It is hard to overstate the popularity and cultural impact Sesame Street had in the United States when it started airing in November 1969. In addition to its novel educational content, the show portrayed an urban integrated community in a positive light, Black actors cast as role models and figures of authority, married women working, and friendly egalitarian interactions between cast members of different races. The contrast with other TV shows, where women and minority groups were often underrepresented or stereotyped, was stark. For many young kids, Sesame Street was their first glimpse at a diverse America, allowing them to form strong bonds with fictional characters whose race did not always match their own.

The sense that children may be especially sensitive to media has made representations of race and gender topics in child media a contentious topic for policymakers and parents. Yet despite this concern, evidence of how minority and gender representations in children’s media impacts kids is limited. We know the media can impact important behaviours (DellaVigna and La Ferrara 2015, Blouin and Mukand 2019, Jensen and Oster 2009) and that interpersonal contact with out-groups can help reduce prejudices (Corno et al. 2022, Rao 2019, Boisjoly et al. 2006). Less is known about whether the media, particularly children’s media, can contribute to prejudice reduction and influence long-run societal outcomes such as voting, when millions of Americans get to express preferences for representatives that may be influenced by candidate demographics.

Capturing the impact of minority and gender representation in children’s media

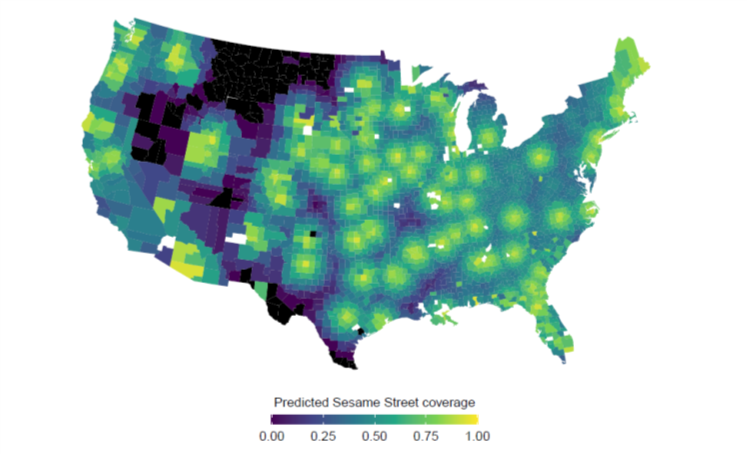

To study this, we use the same strategy as Kearney and Levine (2019) which examined the educational impacts of Sesame Street. Sesame Street was primarily watched by preschool aged kids. If you were already in elementary school when the show started airing in 1969, you probably watched the show much less than someone just a few years younger who was preschool aged. There was also a lot of geographic variation in the quality of the show’s broadcast signal. This combination of age and geographic differences in exposure allows us to pinpoint the effects of Sesame Street. Using people who were between the ages of 1 and 10 in 1969, we compare differences between the younger and the slightly older cohorts in high coverage counties. We then make the same comparison for low coverage counties and compare the two. In low coverage counties, cohort differences will only reflect general time trends, whereas in high coverage counties cohort differences pick up the additional impacts of Sesame Street.

Figure 1: Estimated county coverage rates of Sesame Street in 1969 as calculated in Kearney and Levine (2019)

With this strategy in hand, we can look at how higher Sesame Street broadcast coverage rates in 1969 impacted voting for US House Representatives decades later, between 2006 and 2020, using data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES). We can also look at long-run impacts on implicit biases using data from Project Implicit, an online platform that makes implicit association tests (IATs) available to the public. Several striking findings emerge.

Better Sesame Street coverage increased political knowledge and voter turnout

In all the different types of elections we look at, regardless of who appears on the ballot, we find that the Sesame Street cohorts in higher coverage counties are more likely to turn out to vote than slightly older cohorts in their county. When the share of households that could pick up a Sesame Street signal was 20 percentage points higher, voter turnout in the Sesame Street cohorts was 2.8 percentage points higher. Consistent with this, respondents from the Sesame Street cohorts are more politically knowledgeable and engaged. The Sesame Street cohorts are more likely to have moderate political views where older cohorts might express no political identity. Extreme political identities were not affected.

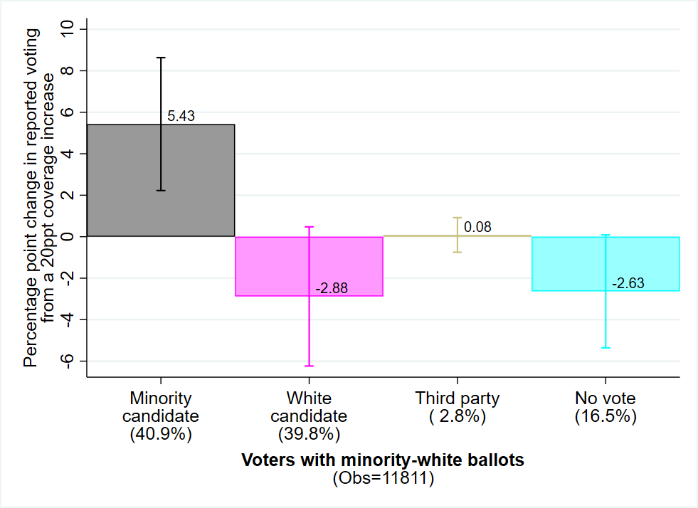

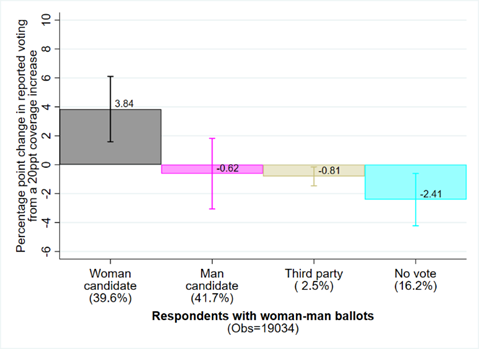

Better Sesame Street coverage increased reported voting for minority and women candidates

In places where a minority candidate and a white candidate run against one another, each representing one of the major political parties, the Sesame Street cohorts were more likely to report that they voted for the minority candidate, regardless of the party they were running for. When the share of households that could pick up a Sesame Street signal was 20 percentage points higher, reported voting for the minority candidate in the Sesame Street cohorts increased by 5.4 percentage points. About half of this effect is due to the increase in turnout, while the remainder comes from reduced reported voting for white candidates. A similar analysis shows that the Sesame Street cohorts are also 3.8 percentage points more likely to report votes for women candidates when Sesame Street signals were 20 percentage points higher.

Figure 2: Reported vote by respondents facing ballots with a minority candidate and white candidate (panel a) or a woman candidate and man candidate (panel b)

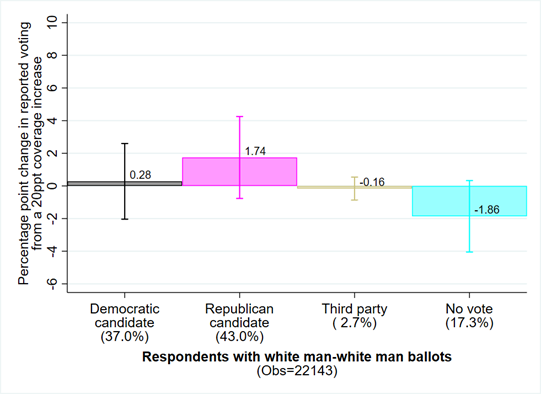

On ballots where the main candidates were two white men, better Sesame Street coverage did not benefit one party over the other

Minority and women candidates are more likely to run as Democrats. Could these patterns be explained by a change in the politics of these cohorts? When we focus in on places where both candidates are white men, the increase in turnout increases reported voting for both parties similarly. Consistent with this, our examination of survey questions on policy views and political identity shows that Sesame Street coverage did not alter public opinion in ways that clearly align with either party’s political platform. Though the Sesame Street cohorts are more likely to have a political identity, we see increases in moderate political identities on both sides of the political spectrum. These patterns suggest that the increase in reported voting for minority and women candidates is due to a changed response to these candidates’ demographics, consistent with findings in the implicit bias data.

Figure 3: Reported vote by party for respondents facing ballots where both candidates are white men

Better Sesame Street coverage reduced implicit biases against black people, the most likely explanation for the changes we observe in reported voting patterns

Using the same approach, we analyse scores on racial implicit association tests. White test takers from Sesame Street cohorts have lower measures of implicit racial biases than slightly older cohorts in counties that had high Sesame Street coverage rates in 1969. These differences are detectable even though these tests were taken decades after Sesame Street started airing.

Child mass media is an important lever for reducing persistent patterns of prejudice

Our findings show that child media can reduce prejudice in the long run impacting consequential adult decisions. Media exposure to non-stereotyped minorities and women had important effects, not just as role models for minority kids and girls, but also by impacting the biases and prejudices of all viewers. The importance of representation in the media has increasingly been recognised and debated in policy circles and the popular press. These findings contribute important empirical evidence to help inform these discussions.

References

Blouin, A. and S.W. Mukand (2019), “Erasing ethnicity? Propaganda, nation building, and identity in Rwanda”, Journal of Political Economy, 127(3): 1008-1062.

Boisjoly, J., G.J. Duncan, M. Kremer, D.M. Levy and J. Eccles (2006), “Empathy or antipathy? The impact of diversity”, American Economic Review, 96(5): 1890-1905.

Corno, L., E. La Ferrara and J. Burns (2022), “Interaction, stereotypes, and performance: Evidence from South Africa”, American Economic Review, 112(12): 3848-3875.

DellaVigna, S. and E. La Ferrara (2015), “Economic and social impacts of the media”, in Handbook of Media Economics, Vol. 1, North-Holland: 723-768.

Duquennois, C. and J. Zeng (2024), “Casting roles, casting votes: Lessons from Sesame Street on media representation, racial biases, and voting”, Working Paper.

Jensen, R. and E. Oster (2009), “The power of TV: Cable television and women's status in India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(3): 1057-1094.

Kearney, M.S. and P.B. Levine (2019), “Early childhood education by television: Lessons from Sesame Street”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(1): 318-350.

Rao, G. (2019), “Familiarity does not breed contempt: Generosity, discrimination, and diversity in Delhi schools”, American Economic Review, 109(3): 774-809.