A participant-centred planning intervention, that prompted farmers to think through all potential income and expenditures using categorisation and labelling, leads to smoother consumption across seasons, more savings and higher farm yields for Zambian farmers.

Seasonal hunger is a pernicious reality across low- and middle-income countries, especially those with large agricultural sectors. Periods of scarcity between harvests, known as the “hungry season,” have well-documented negative impacts on wellbeing, child development and economic outcomes. During the hungry season, households face food shortages and consume less calories (Fink et al. 2020). Children exposed to such seasonal fluctuations are shorter as adults and attain less education (Christian and Dillon 2018). Households often adopt coping strategies that reduce their productive capacity, like doing informal wage labour at the expense of working on their own farms (Fink et al. 2020) and selling productive assets like livestock (Mayanja et al. 2015, Rademacher-Schulz et al. 2014, Zug 2006).

In our study setting of rural Zambia, farming households primarily depend on their annual maize harvest to provide the bulk of their income for the entire year - and they typically run out of maize stocks and savings months before the next harvest. In our recent study, we explored one avenue for dealing with this annual challenge of seasonal hunger, by applying insights from psychology and behavioural economics to help people use past experiences to inform future planning.

Designing a planning tool using psychological insights

A body of research in psychology has demonstrated that people often have a difficult time planning for the future. This has been experimentally demonstrated across a range of behaviour with real life implications, including saving for retirement, committing to getting vaccinated, attending important medical screenings, voting, and more (Benartzi and Thaler 2013, Rogers et al. 2015). We adopted principles from this work to design a simple planning intervention that gives farming households a structured way of budgeting their available harvest income to cover their upcoming expenses; this leads to a more realistic plan and a greater urgency around the need to save early in the season.

We carried out a randomised intervention with over 800 smallholder maize-farming households in Eastern Province, Zambia. Individuals worked through an hour-long planning exercise with a trained surveyor. The exercise prompted farmers to think through all potential income and expenditures using associative categories to aid memory retrieval. For example, a farmer is more likely to remember she will need to spend on school books if she is asked to recall “school fees” rather than all expenditures as a whole. This increased recall of expenditures reduces farmers’ over-optimism about how long their savings will last. To promote cognitive engagement, and to avoid the need for more complex math, we designed a visual planning board that depicts the income and spending categories, and allows farmers to consider their available harvest, represented by thumbtacks, and allocate it over a set of expense categories. Drawing on the benefits of mental accounting, we also provided farmers with physical labels that correspond to each spending category; they attached these labels to their maize bags to reflect their spending plan for the upcoming year. Consequently, if they have labelled a given maize bag for food consumption in February, and find themselves drawing from that bag in January, this lets them know they are over-spending relative to their plan.

We collected data on food consumption, savings, beliefs, labour and farm yields over the course of the year to understand how the planning exercise impacts health and economics outcomes.

Planning helps poor households save more into the hungry season

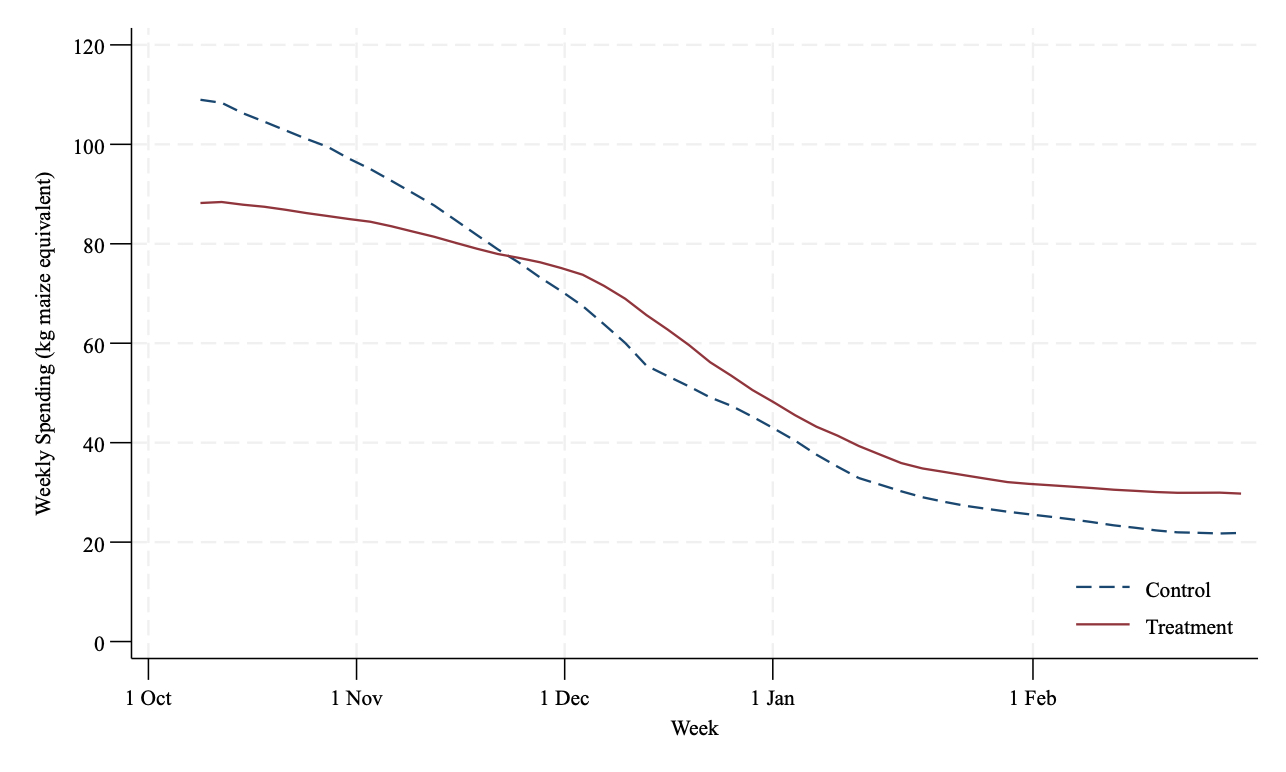

Relative to a control group, households that participated in the planning intervention increased their expected expenses by 42%; an effect driven by an increase in the likelihood of planning for expenses that were small, irregular and uncertain. These households then spent less right after the harvest (as seen in Figure 1) and had 15% higher savings two months later. They entered the hungry season, typically a time of scarcity, with an additional month’s worth of food. Households that used the planning tool also invested more in their own farms and had 9% higher farm revenue at harvest—entering the next agricultural cycle with more income than the control.

Figure 1 Weekly spending over the agricultural cycle

Why do households not save more?

We provide evidence that a psychological phenomenon we call “retrieval failures” affects individuals’ ability to plan and save. Individuals have a difficult time remembering and considering the full range of numerous uncertain, small and infrequent expenses for which they must save. This makes them feel richer in the present, leading them to save less in the early part of the cycle, resulting in lower savings later in the cycle.

Our results support this hypothesis. First, we found that despite years of experience with maize cultivation and the annual hungry season, farmers were overly optimistic about how much maize stock they would have during the hungry season when asked to make predictions. When we asked households to forecast how much maize they would have three months after baseline (the early hungry season), 80% were overly optimistic: when we returned in three months, their savings were less than their forecast. Further, 65% had less maize than their prediction of a “worst case” scenario. This suggests that households are overly optimistic about their own situation and believe the next year will be different than the last despite years of experience. Second, households systematically under-estimate their actual expenses, a phenomenon well-documented across a range of contexts (Peetz and Buehler 2009, Sussman and Alter 2012, Howard et al. 2022). When asked to forecast their non-food expenses over the year households’ actual expenditures were 100% higher than their predictions.

Planning interventions can reduce under-saving in low-income households

Building on our findings in Zambia, we hypothesise that retrieval failures are prevalent across many contexts, affecting different populations and exacerbating consumption smoothing challenges. We explored this further with a sample of low- and middle-income US households through a short online survey, asking respondents to first provide estimates of their total income and total expenses, and then provide more detailed estimates by prompting respondents with associative categories. We documented that individuals in the US sample were over-optimistic in forecasting their total expenses and savings, but not their income, and that using categories of expenses helps individuals provide more accurate estimates of expenses. We believe our findings can help guide policies that address “under-saving” in low-income populations by incorporating beliefs into smoothing and savings interventions.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) as well as the Psychology and Economics of Poverty Initiative and the Center for Effective Global Action at UC Berkeley, International Growth Centre, USAID Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Markets, Risk & Resilience at UC Davis, National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development Program, and the Weiss Family Fund. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

References

Augenblick, N, B K Jack, S Kaur, F Masiye and N Swanson “Retrieval Failures and Consumption Smoothing: A Field Experiment on Seasonal Poverty” Working Paper.

Benartzi, S, and R H Thaler (2013), “Behavioral economics and the retirement savings crisis,” Science, 339(6124): 1152-1153.

Christian, P, and B Dillon (2018), “Growing and learning when consumption is seasonal: Long-term evidence from Tanzania,” Demography, 55(3): 1091-1118.

Fink, G, B K Jack, and F Masiye (2020), “Seasonal liquidity, rural labor markets, and agricultural production,” American Economic Review, 110(11): 3351-3392.

Howard, R C C, D J Hardisty, A B Sussman, and M F Lukas (2022), “Understanding and neutralizing the expense prediction bias: The role of accessibility, typicality, and skewness,” Journal of Marketing Research, 59(2): 435-452.

Mayanja, M N, C Rubaire-Akiiki, T Greiner, and J F Morton (2015), “Characterising food insecurity in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Uganda using a consumption coping strategy index,” Pastoralism, 5(1): 11.

Peetz, J, and R Buehler (2009), “Is there a budget fallacy? The role of savings goals in the prediction of personal spending,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(12): 1579-1591.

Rademacher-Schulz, C, B Schraven, and E S Mahama (2014), “Time matters: Shifting seasonal migration in Northern Ghana in response to rainfall variability and food insecurity,” Climate and Development, 6(1): 46-52.

Rogers, T, K L Milkman, L K John, and M I Norton (2015), “Beyond good intentions: Prompting people to make plans improves follow-through on important tasks,” Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(2): 33-41.

Sussman, A B, and A L Alter (2012), “The exception is the rule: Underestimating and overspending on exceptional expenses,” Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4): 800-814.

Zug, S (2006), “Monga-seasonal food insecurity in Bangladesh: Bringing the information together,” Journal of Social Studies-Dhaka, 111: 21.