Communicating tailored high teacher expectations led to large improvements in student performance in Pakistan. Providing reminders about past performance also had similar effects, particularly in environments with low parental literacy, whilst peer matching only helped when peers are similar.

We need effective strategies to enhance student achievement in low- and middle-income countries

We are currently grappling with a learning crisis in low- and middle-income countries with over 250 million students lacking basic literacy and numeracy skills (Crouch et al. 2021, UNESCO 2014). This situation highlights the urgent need for cost-effective and inclusive practices to improve student performance.

In our research (Asim, Jain and Khandelwal 2024), we explore how teachers can be leveraged to improve student motivation and academic achievement. Specifically, we investigate whether teachers setting personalised high expectations of student effort and performance can improve student outcomes. We provide causal evidence on how the effect depends on the level at which expectations are set, how it compares to simply providing information about past performance, and whether it can be strengthened by leveraging classroom peers.

Eliciting expectations and the design of our experiment

Typically, teachers often selectively convey high expectations of performance to those already performing well. This selective communication can exacerbate educational inequalities. To explore the impact of delivering high teacher expectations to all students, we conducted an experimental study in collaboration with a large private school chain in Pakistan. Our study involved 288 classrooms across 15 schools.

We first collected student-specific teacher expectations using administrative data to remind math teachers of their students' most recent math test scores. Teachers were then asked to fill in realistic expectations for their students’ future performance by responding to the following statements:

- "I expect the student to work hard and improve to achieve at least X (out of 100%) in upcoming exams and tests" (referred to as 'High Expectations').

- "I expect the student to work hard and improve and I think that even Y (out of 100%) is achievable in upcoming exams and tests" (referred to as 'Very High Expectations').

Subsequently, we randomly divided the sample classrooms into three groups: an Expectations Arm, a Peer Arm, and a Comparison Group, which was further split into an Information Arm and a Pure Control Arm.

Students in the Expectations Arm randomly received one of the two statements of teacher expectations (i.e. ‘High’ or ‘Very High’), along with a custom-designed infographic encouraging them to work towards achieving the expectation. Students in the Peer Arm also received a similar infographic along with their respective individual expectations but were additionally randomly matched with a classmate and asked to encourage each other. Students in the Information Arm received an infographic with a reminder about their previous math exam performance, while the Control Arm students received no message. Private emails were sent to each student, and teachers were blind to the treatment status to prevent selective changes in their efforts. Comparison with students in pure control classrooms ensures that the measured treatment effects do not arise due to negative spillovers among treated and control students.

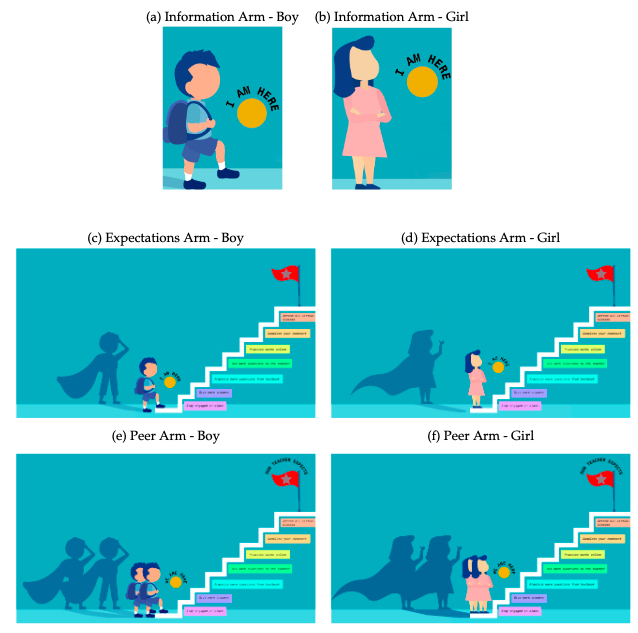

Figure 1 shows the infographics sent to students in different treatment arms.

Figure 1: Infographics sent to students in various treatment arms

Note: The circle and the flag in the above infographics contained the current performance and teacher expectation of each student respectively. Students in the peer arm received their individual expectation like students in the Expectations Arm but were sent an additional empty infographic shown in (e) and (f). Students in the pure control group received no infographic at all. The text under the stairs lists general tips (elicited from teachers) such as being more engaged in the classroom, completing homework, etc. that teachers reported they typically convey in the classroom already.

Key findings: How do teacher expectations impact students?

The experiment yielded the following key insights:

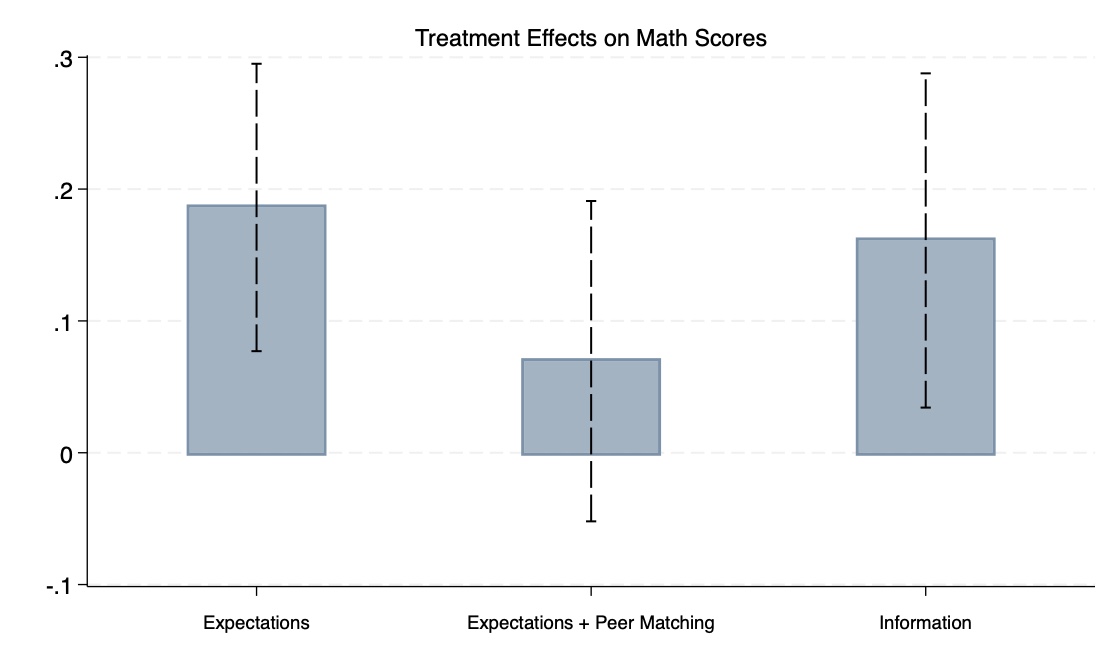

Figure 2: Average treatment effects on standardised math test scores

1. High teacher expectations improve student achievement.

As shown in Figure 2, we find that students in the Expectations Arm scored 0.19 standard deviations higher in their math exams than those in the Control Group. This effect was stronger (0.23 standard deviations) for students who randomly received the 'Very High' teacher expectation statement. In fact, we find that a 10 percentage point increase in the gap between teacher expectations and the student's baseline score led to a 0.1 standard deviation increase in impact. Notably, students predicted to perform the worst scored 0.33 standard deviations higher in the Expectations Arm compared to comparable students in the Control Group. 80% of students in a follow-up survey interpreted the infographic in terms of a goal and revealed that would feel encouraged/motivated by it.

2. Information provision about previous test scores is also effective, particularly in schools with lower parental literacy.

Students in the Information Arm also scored 0.16 standard deviations higher than those in the Control Group. Although the treatment effect is not statistically different from the Expectations Treatment Arm, the treatment effect is significantly higher in low parental literacy schools (compared to high parental literacy schools), suggesting that the infographic made performance information more accessible to parents.

3. Peer matching helps only when peers are similar.

Interestingly, the average treatment effect of the Peer Arm was not statistically distinguishable from zero. However, the effect was positive and significantly higher for matched peers with similar baseline characteristics (e.g. achievement and teacher expectations). At the same time, it was negative for those matched with peers having higher baseline scores or expectations. This aligns with what students reported in a follow-up survey - they felt motivated when paired with similar peers and discouraged when paired with dissimilar peers.

Policy recommendations for schools in low- and middle-income countries

Our findings offer the following policy insights. Firstly, teachers can be encouraged by schools to set and communicate high expectations for all students. Our study offers a low-cost, non-invasive, and sustainable way in which teachers can encourage all students, not just top performers. Secondly, schools can provide students with reminders from their teachers of their previous performance to boost their academic achievement. Our study shows this is especially useful in settings where parents are less literate. Finally, teachers can consider forming peer study groups with pairs who have similar baseline characteristics to avoid negative morale effects. Our findings suggest that this kind of pairing can lead to large improvements in performance.

References

Asim M, R Jain and V Khandelwal (2024) “Great Expectations? Experimental Evidence from Schools in Pakistan” Working Paper.

Crouch, L, M Kaffenberger and L Savage (2021), “Using learning profiles to inform education priorities: An editors’ overview of the Special Issue.” International Journal of Educational Development, 86: 102477.

UNESCO (2014), 'EFA global monitoring report. teaching and learning: Achieving quality for all’