Entrepreneurs with mentors enjoy an increase in profits and manage supplier costs better. Mentorship is also more cost effective than business classes.

Entrepreneurship in urban slums

Mary operates a small business in an urban slum called Dandora, located on the outskirts of Nairobi.1 Dandora has a reputation for poverty and violence. When Mary graduated from secondary school, she found that there were no jobs available. Like many people in her community, Mary decided that opening a small business would be the most promising way to secure an income.

Nothing in her experience or education up to that point had prepared Mary to be an entrepreneur. Initially she operated a milk business. Every day she bought milk in the large markets, carried it back to Dandora and sold it on the street. Yet her business made very little profit. She faced fierce competition, had few customers, and by the end of each day her milk had spoiled. Mary’s business had many problems, but she lacked the knowledge or experience to find solutions.

Microenterprises in developing countries

Mary’s situation is common in Dandora and around the developing world. In developing countries, many people are unable to secure jobs and instead open their own microenterprises. According to Gollin (2008), entrepreneurs account for 75.3% of workers in Nigeria, 74.5% of workers in Bangladesh, and 50.4% of workers in Guatemala. This is compared to only 8.2% of workers in the US and 10.6% of workers in the UK. In developing countries, large numbers of workers operate their own firms but many lack the skills they need to be successful.

This lack of business skills matters for the profits generated by entrepreneurs like Mary. McKenzie and Woodruff (2016) show that an improvement in business practice of one standard deviation is associated with 35 % greater labour productivity. If the business skills of young microenterprise owners could be developed effectively, that could have an important impact on their economic wellbeing. This begs the question: what is the best way to impart business skills on the entrepreneurs that need them?

Improving business skills

Formal business classes

Until recently, the most common approach to improving business skills has been formal business classes. These classes teach entrepreneurs general concepts like accounting, marketing, business planning and cost control. Billions of dollars have been spent and millions of entrepreneurs have received this type of training (Blattman and Ralston 2015). However, in their review of the large literature that measures their impact, McKenzie and Woodruff (2014) found that there is limited evidence that these classes increase business profit.

Business experience

Yet even in the most challenging environments in the developing world, some entrepreneurs manage to be profitable and even thrive. Grocery store owners started their careers operating small fruit carts, and furniture manufacturers with dozens of employees started with none. These successful entrepreneurs have learned how to overcome the challenges of their local context over a lifetime of business experience. These success stories suggest that profitable entrepreneurship is possible. If the business skills of those successful firms could be harnessed and transmitted to new entrepreneurs, their businesses could substantially improve.

The study

Mentorship

In a recent paper, we ask if successful local business owners can be effective mentors to young, inexperienced entrepreneurs (Brooks et al. 2017). To answer this question, we conducted a randomised controlled trial. We identified the most experienced and profitable entrepreneurs in the local community and assigned young entrepreneurs to be their mentees. Compared to traditional business classes, a key strength of mentorship is that it does not require those implementing the programme to know how to operate a successful business in the local context. Instead, mentors and mentees meet together to discuss whatever topics or approaches they think will most benefit the mentee’s business.

Comparative analysis

To compare the effect of the mentorship programme with traditional business training, we conducted business classes for a comparable group of entrepreneurs. Over the course of a year, we studied both groups as well as a control group who received neither classes nor mentors. Assignment to the three groups was random, so by comparing outcomes of the mentees and the control group we can measure the causal effect of mentorship. This also allows us to compare the mentorship and classroom groups to see how the two different approaches affect skill acquisition, behavior, and economic outcomes.

Findings

As a part of the study, in October 2014, we matched Mary with a successful grocer in Dandora to serve as her mentor. She told Mary that selling milk was too risky, and that she should choose a different product. She suggested selling shoes instead, since the product is durable and the markups are high. They discussed where she could purchase her inventory and strategies to increase sales. Now Mary makes substantially more profit, and has secured a steady income to support her family. Moreover, she formed a durable relationship with her mentor that has continued long after the study period has ended.

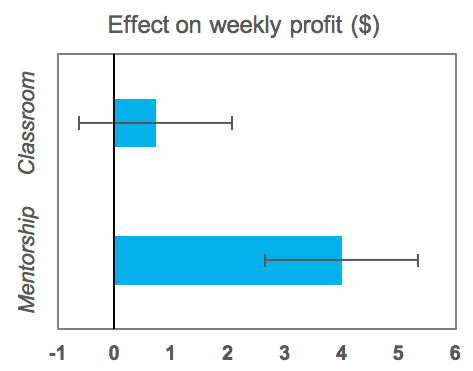

Mary’s experience is representative of the broader results in the study. We find that the mentees experienced a statistically significant increase in profits of about $4 per week over the course of the year, which is 20% of average profits, compared to participants in the control group, while the traditional business training had an effect on profit that was statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Importantly, mentorship was also cost effective: every $1 spent on the mentorship programme translated to $1.73 in greater profit for the mentee over the course of the year. This compares favorably to the $0.25 in the classroom group, and to the returns realised from many other microenterprise interventions.

Figure 1 Treatment effects on weekly profit, in US dollars

Though there may be a variety of important ways that mentorship and classroom training are different, we focus on observable differences in behavior between participants in the two groups. We find that members of the classroom group adopt practices covered in class like accounting or marketing, but these changes fail to translate into an increase in profits.

Meanwhile, the most notable changes in behavior in the mentorship group related to cost management. Mentees had a significantly higher rate of supplier switching than the control group. Supplier churning is high in Dandora, where 62% of members of the control changed their supplier in the first months of the study period. Even so, mentorship caused a statistically significant 19% increase in supplier churning, which suggests that mentors play an important role in helping mentees find lower cost suppliers. This emphasises the fact that mentors impart actionable and localised information to their mentees.

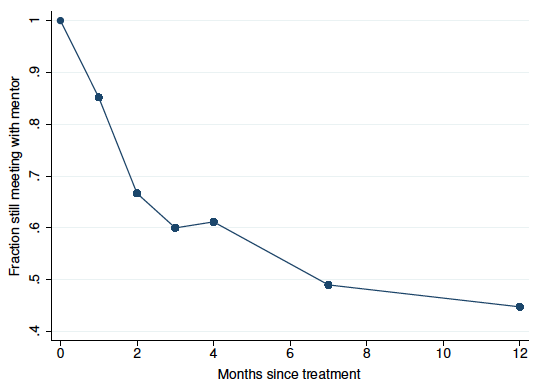

Figure 2 Percentage of mentor-mentees still meeting after programme end

Despite these promising results, mentorship on its own is not the full solution. Mentor-mentee pairs were unexpectedly durable over the year following the intervention, with approximately half of all pairs still meeting after seven months. While mentees who persisted in meeting with their mentors continued to reap benefits, those that stopped meeting quickly lost the profit effect, so the average effect of mentorship faded over time as matches dissolved. This suggests that mentees may not be accumulating general problem-solving or management skills, and that the benefits of mentorship accrue only in the short run.

Going forward

Mentorship should be coupled with other solutions to both increase profits in the short run, and to support their long-run development. Furthermore, a complete business training programme should strike the right balance between localised, actionable information and abstract, conceptual principles. The local expertise of mentors combined with business classes might be more effective over the entrepreneur’s whole career than either approach alone.

Photo credit: Ariel Jacobson/uusc.org

References

Blattman, C and L Ralston (2015), “Generating employment in poor and fragile states: Evidence from labor market and entrepreneurship program”, World Bank Working Paper.

Brooks, W, K Donovan and T Johnson (2017), “Mentors or Teachers? Microenterprise Training in Kenya”, University of Notre Dame Working Paper.

Gollin, D (2008), “Nobody’s Business but My Own: Self Employment and Small Enterprise in Economic Development”, Journal of Monetary Economics 55(2): 219-233.

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2014), What Are We Learning from Business Training Evaluations around the Developing World?”, World Bank Research Observer 29(1): 48-82.

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2016), “Business Practices in Small Firms in Developing Countries”, Management Science, forthcoming.

Endnotes

[1] We are using a pseudonym to protect the privacy of our study participant.