Evidence from the garment industry in Bangladesh shows that it is not obvious that policymakers should try to limit the role of referrals in job hiring

Firms in both developed and developing countries frequently use referrals from current workers to fill job vacancies. But is this a good thing? Since wealthy people tend to know well-connected people, network hiring can reinforce inequality (Calvo-Armengol and Jackson 2004). And if hiring well-connected workers is primarily an act of nepotism or a way for firms to find new workers easily, then there is little efficiency gained through the use of networks. Indeed, some policymakers have tried to counteract network effects by promoting information about job opportunities to potential workers who lack high-quality social networks (Banerji et al. 2010).

However, what if hiring through referrals actually increases the quality of workers? If so, promoting information about jobs will not necessarily motivate companies to hire unconnected workers. Moreover, discouraging hiring through networks could actually hurt efficiency.

Referrals and worker effort

I collected data on workers in Bangladeshi garment factories to explore why firms are hiring using referrals from current workers. These data suggest that firms like to hire referred workers because these workers work particularly hard, lest the firm punish the provider of the referral if they do not. This model is similar to joint liability in microfinance: in both cases, a formal institution takes advantage of social ties between participants, who can monitor each other more closely than the institution can.

This ability to motivate workers to work hard is particularly useful in industries like the garment industry in Bangladesh. Firms often use the promise of higher future wages to induce effort, but employment spells are relatively short in this industry for three broad reasons:

- Workers tend to switch between firms when they get large orders.

- Workers often drop in and out of the labour force due to caregiving demands.

- Careers are relatively short.

Similar conditions characterise labour markets in many other large manufacturing firms worldwide.

Data collection

Providing evidence for this model requires data on the labour market outcomes of both the provider and the recipient of the referral. To gather this data, I conducted a household survey of 972 garment workers in Bangladesh in 60 villages outside of the capital, Dhaka, from August to October 2009. Each sampled garment worker was asked about her entire employment and wage history.

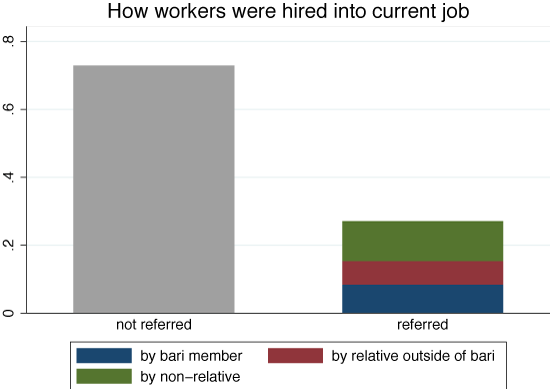

As Figure 1 indicates, referrals are common in this context: 32% of workers received a referral in their current job. 65% of referrals came from relatives, most of which (and 45% of referrals overall) occur between workers living in the same extended family compound, called a bari.

Accordingly, sampling at the unit of the bari allowed me to capture both the referral provider and recipient in the survey. Therefore, in employment spells where the surveyed worker received a referral from someone living in the bari and working in the garment industry at the time of the survey, the work history of the recipient can be matched to the work history of the provider. I can also observe the outcomes of the same two workers when they were working in separate factories.

Evidence for the relationship between referrals and worker effort

A direct test of the model would assess whether referred workers put forth more effort than non-referred workers. However, the whole reason that firms have trouble providing incentives for high effort is that firms cannot perfectly observe workers’ effort. Workers work in teams, quality is hard to observe, and new orders of uncertain difficulty come in regularly. Firms do get a noisy signal of the worker’s effort, and update wages accordingly when it is time to give raises.

I therefore conduct an indirect test of the relationship between referrals and worker effort that looks for evidence of a joint contract between the firm, the provider, and the recipient of the referral. Specifically, the wages of the provider should reflect the outcome of the recipient, so that the wages of the provider and recipient should move together.

The central challenge in conducting this test is that there are many reasons why two members of the same bari might have correlated wages. For instance, they may all be motivated to work hard to raise funds to take care of a sick relative. To rule out many of these alternate sources of wage correlation, I take advantage of two key control groups:

- Other bari members working in the same factory at the same time as the referral pair.

- The wages of the provider and recipient at times when they are not working in the same factory.

Results

I conduct a test that assesses whether the provider and recipient of the referral have a differentially stronger wage correlation than other pairs of bari members when working in the same factory, versus when they are not. Indeed, I find that when the recipients wage goes up by 10%, the provider’s wages goes up by 3.9%, an effect which is much stronger than the wage correlation between bari members working in the same factory, or the wage correlation between the pair when they are not working together. This effect holds even among workers who are not on the same production line use the same machine or work in the same position. These results are consistent with the firm’s offer of a joint contract to the referral provider and recipient, which provides the recipient incentive to work hard.

Referrals and efficiency gains

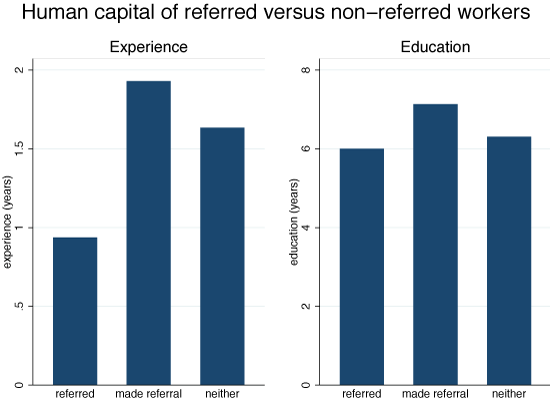

While I do not have the firm-level productivity data needed to confirm that hiring referred workers helps firms boost their productivity, I can provide indirect evidence of efficiency gains by looking at the characteristics of workers hired with and without referrals. Figure 2 indicates that workers hired with referrals have 0.4 fewer years of education and 0.8 fewer years of experience than other workers. Firms appear more likely to take a risk on an untested worker if that worker has been referred to them, and referrals help firms profitably hire workers that might not have jobs otherwise.

Concluding remarks

This evidence thus suggests that referrals help garment factories in Bangladesh hire employees who will work hard. So, attempts to disseminate information about job openings will not undo network effects; firms will still hire an observably bad worker only if she receives a referral from a current worker who is willing to allow her own wages to be decreased if the recipient performs poorly. Nor is it obvious that policymakers should attempt to minimise the role of referrals in job hiring since referrals help firms feel confident that all their workers are working hard.

Many labour markets, particularly in the developing world, are also characterised by the high turnover that makes effort difficult to induce using long-term contracts, and likely use referrals in a similar to the Bangladeshi garment factories I studied. Policymakers hoping to ensure equitable job access to potential workers in these labour markets without access to high-quality social networks should focus instead on helping firms develop alternative ways (such as insurance against workers’ mistakes) to receive high effort in their workers.

References

Banerji, A, W Cunningham, A Fiszbein, E King, H Patrinos, D Robalino and JP Tan (2010), “Stepping up skills for more jobs and higher productivity."

Calvo-Armengol, A and M Jackson (2004), "The effects of social networks on employment and inequality", American Economic Review 94(3): 426-454.