The bulk of this century’s population growth lies in the exceptionally high demand for children of poorer households in sub-Saharan Africa

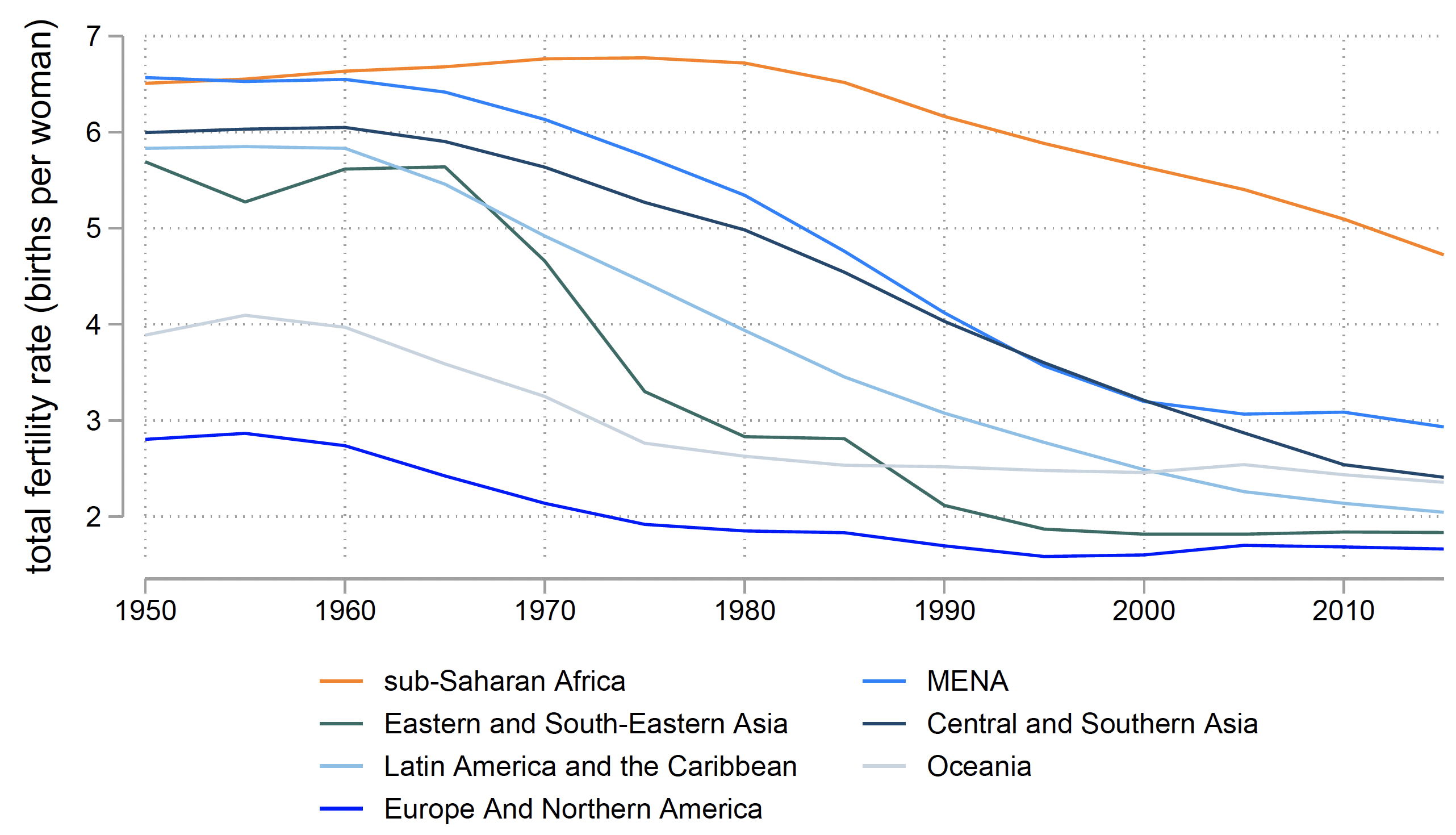

More than three quarters of global population growth over the next 80 years is expected to take place in sub-Saharan Africa, where the population is projected to double by 2050 and almost quadruple by 2100 (UN WPP 2019). Persistently high fertility rates underlie these predictions; women were still giving birth to around five children on average on the sub-continent in 2015, as opposed to two to three in all other developing regions (Figure 1). Demographers recognise that the decline in the number of children born per woman started later and has been moving at a slower pace in this region than elsewhere – a pattern they refer to as a ‘unique fertility transition’ (Bongaarts and Casterline 2013, Bongaarts 2017).

Figure 1 Average total fertility rate, 1950-2015

Source: UN World Population Prospects, 2019.

Notes: Regions correspond to the SDG regions provided in the source data. The orange curve depicts the fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa, which is characterized by a later onset and slower pace than that of other low-and middle-income regions.

While this phenomenon is undoubtedly attributable to a combination of factors, accounting for those most thought to play a role in the pace of fertility transitions does not eliminate the gap observed between sub-Saharan Africa and other regions. Conditional on GDP per capita, child mortality rates, median years of female education, and the prevalence of modern contraceptives at the country level, the average sub-Saharan African woman still gives birth to 0.8 more children than her counterparts in the rest of the developing world.

Building on earlier work stressing the importance of the ‘demand side’ in determining the pace of fertility transitions in developing countries (Pritchett 1994), in a recent study (Zipfel 2021), I investigate the hypothesis that this residual gap reflects higher desired fertility on the sub-continent.

Demand for children is higher in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among the poorest households

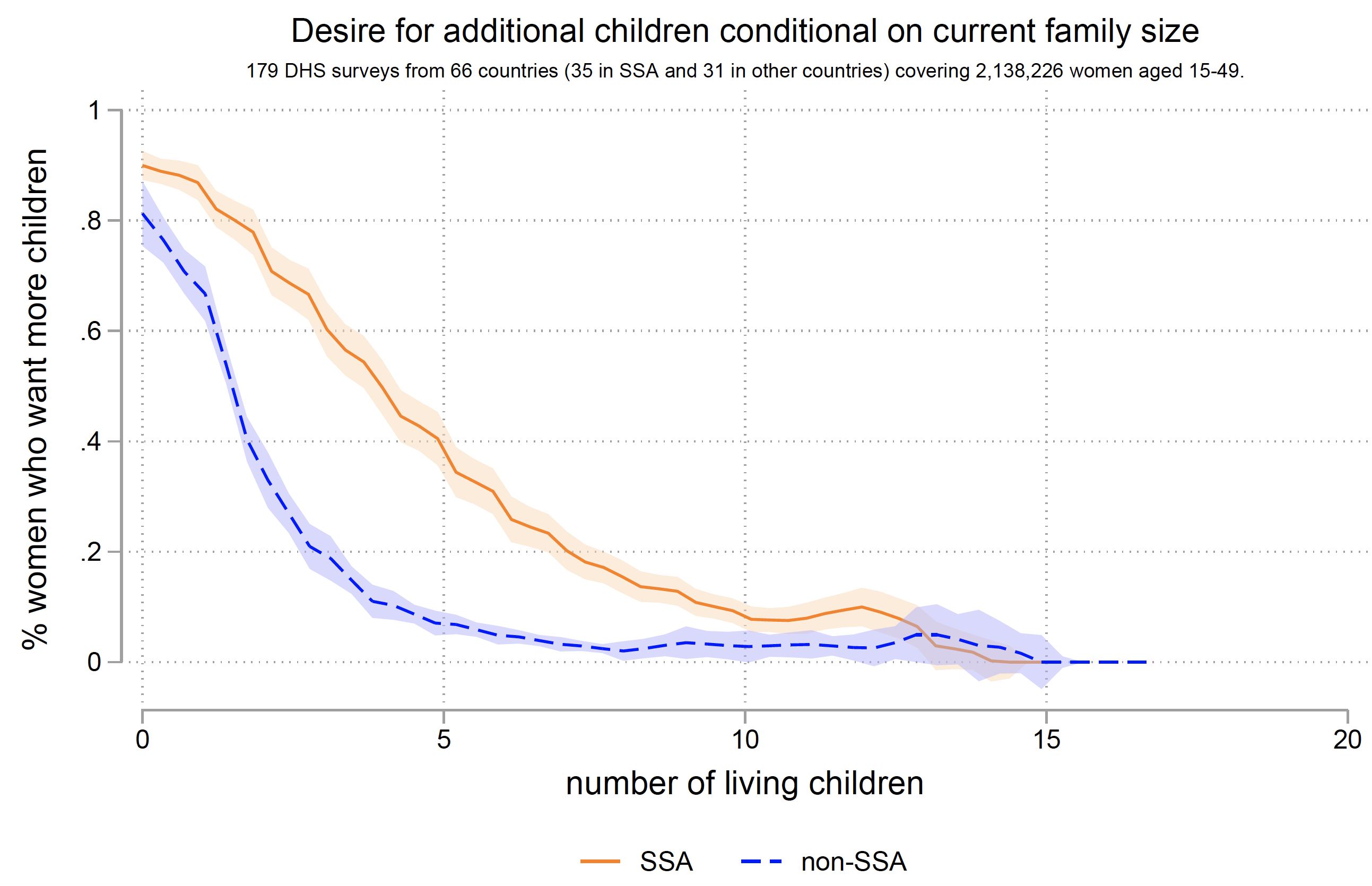

I assemble and analyse micro data from 179 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) covering over two million women of childbearing age (15-49) from 66 countries: 35 from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and 31 from other developing countries (non-SSA). Cross-regional comparisons of within-country patterns in these data reveal a series of important facts. Firstly, preferences for larger families tend to be much more common in SSA, where, for example, 62% of women with three children report wanting a fourth child compared to 19% of their counterparts in other countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Desire for additional children conditional on current family size

Source: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

Notes: The x-axis plots women’s number of living children at the time of the survey. The y-axis plots the share of women responding “yes” to the question “Do you want to have another child?”. The curves plot smoothed fitted values from local polynomial regression estimates with 95% confidence bands. These are fitted from DHS individual data (women’s samples) covering 35 SSA countries (in orange) and 31 non-SSA countries (in blue). The gap between the two curves indicates that women in SSA are significantly more likely to report wanting an additional child when they have between 0 and 10 living children.

This cross-regional disparity could simply reflect fixed cultural differences across countries. Indeed, previous research has highlighted the role of polygyny – i.e. the practice of men having multiple wives, widespread in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa – in driving up demand for children (Tertilt 2005, Rossi 2019). However, comparisons of the association between desired fertility and socioeconomic status across sub-Saharan African and other countries indicate that economic factors may also be at play.

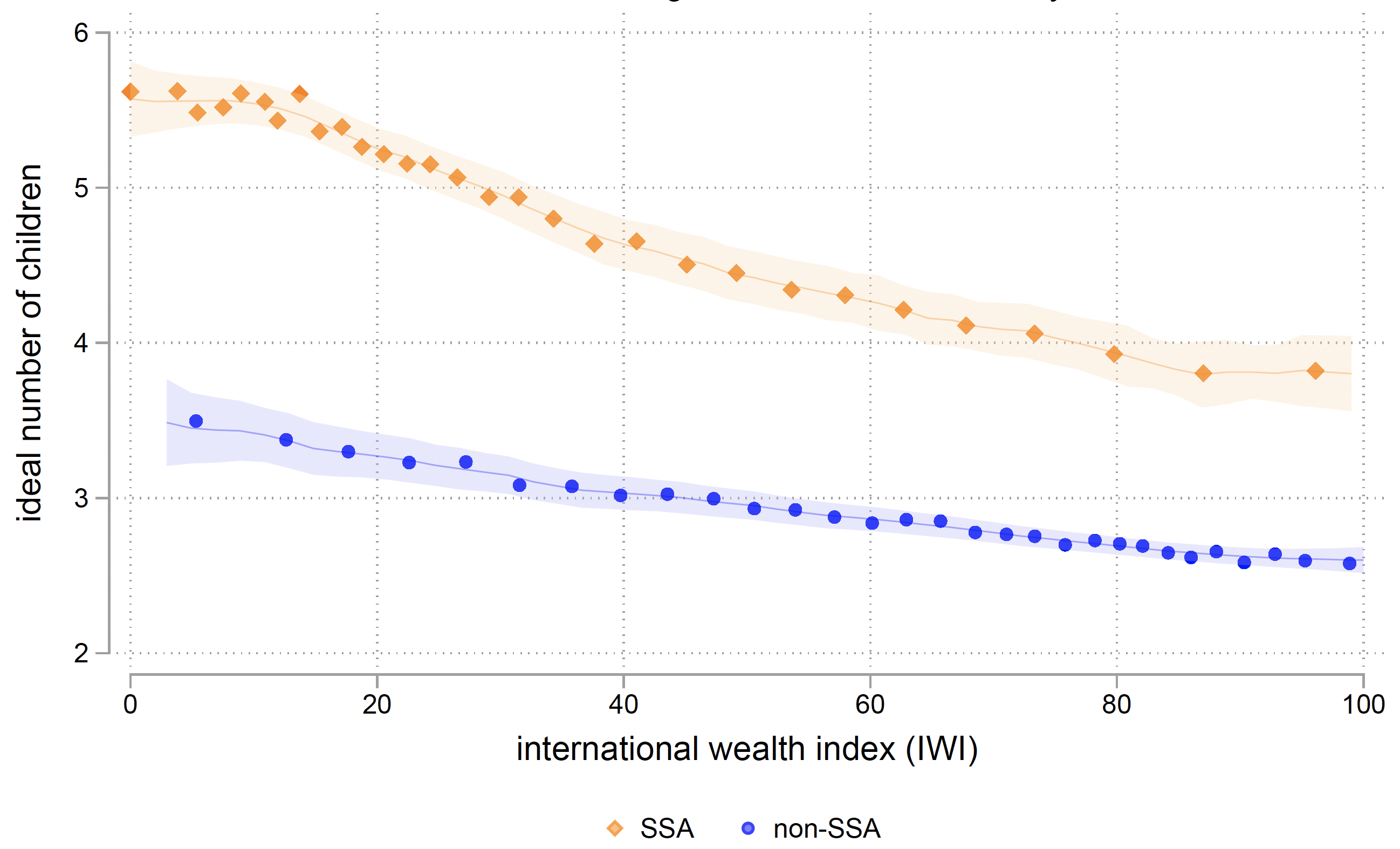

Figure 3 plots women’s average ideal number of children by household wealth. Here, households from all countries in my pooled DHS sample are ranked on the same scale according to the international wealth index constructed by Smits and Steendijk (2015). Two key findings emerge. First, average desired fertility in sub-Saharan Africa stands starkly above the average of other developing countries at all levels of household wealth. Second, this gap is significantly larger for the poorest households, who also represent a much larger share of the population in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 3 Socioeconomic gradients in desired fertility

Source: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the International Wealth Index (IWI).

Notes: The x-axis plots the IWI, constructed from all household-level DHS data by Smits & Steendijk (2015). The lines plot smoothed fitted values from local polynomial regression estimates with 95% confidence bands. Observations are grouped into equal-size wealth bins separately for SSA and non-SSA, depicted by diamond and circular markers respectively. Note: the higher concentration of orange bins towards the left of the x-axis indicates that the SSA population is on average much poorer than that of other low-income regions in the DHS database. The y-axis plots women’s average ideal number of children for each region-bin. The orange curve is noticeably much steeper than the blue curve, indicating a stronger association between socioeconomic status and desired fertility in SSA. Equality of slopes tests are rejected at the 1% significance level.

The economic mechanisms behind high desired fertility

The stronger association between socioeconomic status and desired fertility in sub-Saharan Africa documented in Figure 3 suggests that economic mechanisms contribute to the region’s exceptionally high demand for children. One factor that may not have been given sufficient attention thus far is the nature of jobs available on the sub-continent. Both empirical and theoretical arguments motivate this hypothesis.

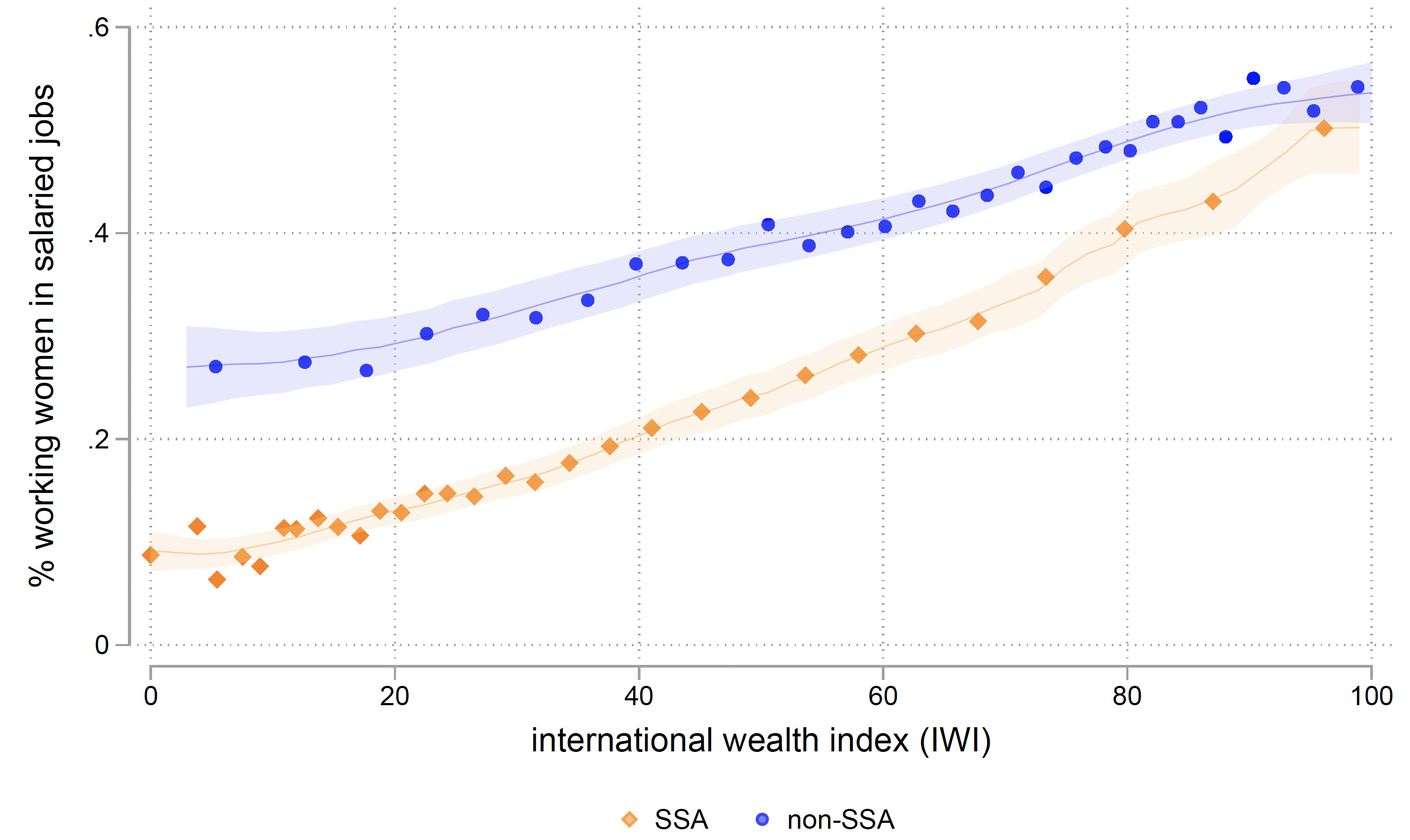

First, as depicted in Figure 4, socioeconomic gradients in job type (i.e., whether the respondent is an employee earning a salary, or a self-employed worker typically not earning regular wages) mirror the difference in slopes from Figure 3. Here, we see that the fraction of working women in salaried jobs is significantly more positively correlated with wealth in sub-Saharan Africa than in other regions. The poorest women are much more likely to be self-employed (for example, working on the family farm in rural areas or in small-scale retail in urban areas) than in other developing countries, and this gap progressively closes as we move up the wealth distribution. Further analysis shows this difference to be particularly pronounced for less educated women in urban settings: holding GDP per capita constant, primary-school female graduates working in urban locations on the sub-continent are 12 percentage points less likely to hold a salaried job than their counterparts in other countries.

Figure 4 Socioeconomic gradients in salaried employment

Source: Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS).

Notes: The x-axis plots the International Wealth Index constructed from all household-level DHS data by Smits & Steendijk (2015). Lines plot the smoothed values of local polynomial regression estimates with 95% confidence bands. Observations are grouped into equal-size wealth bins separately for SSA and non-SSA, depicted by diamond and circular markers respectively. The y-axis plots the share of working women in salaried employment for each region-bin. The orange curve is noticeably much steeper than the blue curve, indicating a stronger association between socioeconomic status and the likelihood of having a salaried job in the region.

Interestingly, in the data, the steeper gradient in desired fertility in sub-Saharan Africa seems to be much more correlated with the type of jobs available (namely, the share of self-employed versus salaried workers in the labour force) than with the sectoral composition of employment as measured by the share of workers reporting agriculture as their main source of livelihood.

Second, the theoretical literature on fertility transitions helps shed light on possible channels through which the set of labour market opportunities available to families could contribute to the difference in slopes observed in Figure 3. Starting with the seminal model of Becker and Lewis (1973), at least two key mechanisms have been shown to explain a negative relationship between parental income and fertility: the time cost associated with children and the ’quantity-quality trade-off’.

According to the first channel, the absence of suitable jobs may deter poor women from reducing their fertility by keeping the opportunity cost of childbearing low. This is in line with empirical evidence from South Asia (Jensen 2012, Heath and Mobarak 2015) and historical evidence from Sweden (Schultz 1985). These studies show that the expansion of female employment opportunities – or an increase in the relative return to women’s labour – can reduce fertility.

The second channel stipulates that an increase in the returns to education should also decrease parents’ desired fertility by making ‘child quality’ relatively more appealing than ‘quantity of children’. Empirical evidence of this channel includes a natural experiment in the US South around 1910, where Bleakley and Lange (2009) show that the eradication of the hookworm disease lowered fertility rates by raising the returns to schooling. In contrast, the near absence of salaried jobs may deter poorer parents from substituting quality for quantity of children by keeping their perception of the returns to education low.

Policy takeaway: Contraceptives alone are not enough

One of the key takeaways from examining desired fertility along the wealth distribution is that much of the gap in fertility rates between sub-Saharan Africa and other regions that is unaccounted for by standard macro-level indicators must lie in the exceptionally high demand for children of the poorest segments of its population.

The expansion of contraceptive access on the sub-continent is an important policy goal, as contraception gives couples the means to achieve their target number of children. A recent field experiment in Burkina Faso also highlights that information campaigns, by correcting beliefs about the side effects of contraception, can increase uptake and thereby lower fertility (Glennerster et al. 2021).

However, if couples genuinely want large numbers of children, contraceptives will by no means be a sufficient condition for accelerating the pace of the fertility decline in sub-Saharan Africa. The findings from this study suggest that expanding the set of economic opportunities available to the poorest families could be an important complement to family planning efforts for reducing fertility in the region. How exactly to achieve this constitutes, perhaps, one of the most pressing challenges in development policy today.

References

Becker, G S and H G Lewis (1973), “On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children”, Journal of Political Economy 81(2,2): S279–S288.

Bleakley, H and F Lange (2009), “Chronic Disease Burden and the Interaction of Education, Fertility, and Growth”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 91(1): 52–65

Bongaarts, J (2017), “Africa’s Unique Fertility Transition”, Population and Development Review 43(S1): 39– 58.

Bongaarts, J and J Casterline (2013), “Fertility Transition: Is sub-Saharan Africa Different?” Population and Development Review 38(1): 153-168.

Glennerster R, J Murray and V Pouliquen (2021), "The Media or the Message? Experimental Evidence on Mass Media and Modern Contraception Uptake in Burkina Faso", CSAE Working Paper 2021-04.

Heath, R and A M Mobarak (2015), “Manufacturing Growth and the Lives of Bangladeshi Women”, Journal of Development Economics 115: 1–15.

Jensen, R (2012), “Do Labor Market Opportunities Affect Young Women’s Work and Family Decisions? Experimental Evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(2): 753–792.

Pritchett, L (1994), “Desired Fertility and the Impact of Population Policies”, Policy Research Working Paper Series 1273, World Bank.

Rossi, P (2019), “Strategic Choices in Polygamous Households: Theory and Evidence from Senegal”, Review of Economic Studies 86(3): 1332-1370.

Schultz, T P (1985), “Changing World Prices, Women’s Wages, and the Fertility Transition: Sweden, 1860-1910”, Journal of Political Economy 93(6): 1126–54.

Smits, J and R Steendijk (2015), "The international wealth index (IWI)", Social Indicators Research 122(1): 65-85. DOI 10.1007/s11205-014-0683-x.

Tertilt, M (2005), “Polygyny, Fertility, and Savings”, Journal of Political Economy 113(6): 1341–1371.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019), "World Population Prospects 2019", Press Release.

Zipfel, C (2021), “Defusing a Population Explosion? Jobs and Fertility in sub-Saharan Africa”, forthcoming.