Has anti-retroviral therapy policy or information access that induces sexual behavioural change been responsible for Malawi’s success in fighting HIV?

With about two million new infections each year, the number of people living with HIV/AIDS has grown to 37 million worldwide. The disease is a major cause of death: about one million people died of HIV/AIDS in 2017 worldwide (UNAIDS 2018). Africa is the most affected continent. Transmissions occur largely through heterosexual sex, which differs from most of the Western world. This accounts for more than 60% of the infected in Africa being female.

The case of Malawi: A decline in HIV/AIDS

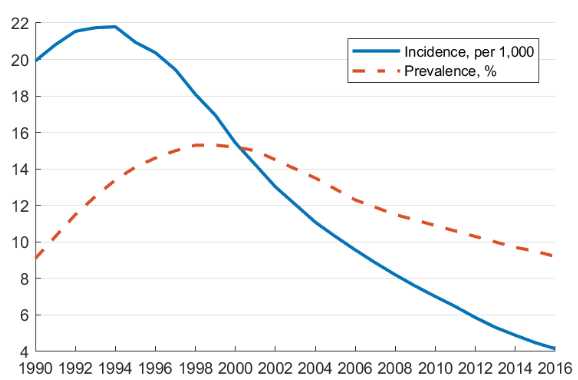

Let us consider Malawi as a case study of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 1 shows that overall HIV prevalence is quite high. Depending on the year, between 10% and 15% of the adult population is HIV positive. The figure also shows that the number of new infections, i.e. the incidence rate, has been falling since 1994. This reduction shows up in the prevalence rate, only with a delay. Therefore, prevalence has been falling since 1999.

Figure 1 HIV prevalence and incidence in Malawi

The decline in HIV/AIDS over the last two decades raises several important questions. What policies have been responsible for the Malawian ‘success story’? More generally, what policies work? And what can be done to bring HIV down even further in the future? It should be noted that many sub-Saharan African countries follow a similar pattern. The results discussed below are relevant to the region at large.

The study: Explaining Malawi’s success

Public policy remedies depend not only on their medical efficacy, but also on the behaviour of the population. A treatment that has been medically shown to reduce HIV transmission at the level of an individual might be less effective if the person starts engaging in more risky sexual practices; see Kremer (1996) and Philipson and Posner (1993) for the theoretical argument. Further, general equilibrium effects seem particularly important too in the context of HIV, as the behaviour of others feeds into the aggregate HIV prevalence rate. This in turn affects an individual’s choice over sexual practices.

In recent work (Greenwood et al. 2019), we build a quantitative model of sexual behaviour to investigate the effectiveness of various public policies in Malawi. A key ingredient in the model is that in each period individuals search for sexual partners (short-term and marital), choose to use a condom or not, or even choose not to have sex at all.

Further, heterogeneity is important: there are men and women, young and old, and the patient and impatient. Further, a fraction of the men are circumcised. Individuals are either healthy or infected, once infected they may be treated with anti-retroviral therapy (ART) or not, and some display symptoms. The model also features exogenous divorces, deaths (related to HIV but also for other reasons), and births.

The model is calibrated to 2004 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data from Malawi. The quantitative model is then simulated under various scenarios to investigate possible reasons for the HIV decline over time. The contribution relative to the previous literature is that the model features both behavioural changes in response to a policy change – as individuals adjust their behaviour to the policy – as well as general equilibrium effects through the aggregate prevalence rate.

The role of anti-retroviral therapy

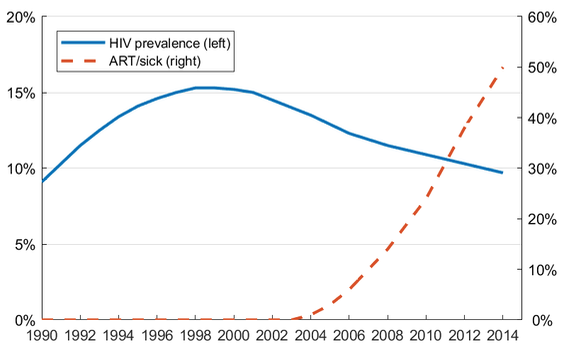

The introduction of ART has been touted as the driver of the Malawian success story (e.g. Government of Malawi 2015: 2). Yet, as Figure 2 shows, ART was not introduced until 2005. Therefore, it cannot be responsible for the initial reversal in the late 1990s. Even so, one might ask whether the subsequent decline can be attributed to the roll-out of ART. By 2014, ART had reached 50% of the infected.

Figure 2 HIV and ART in Malawi: Data

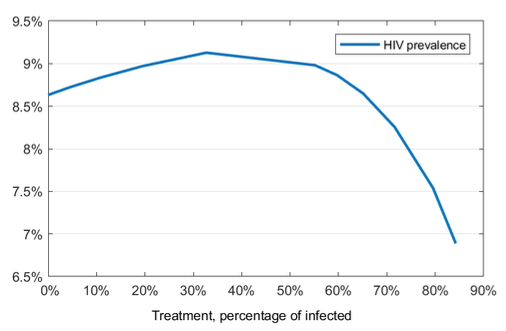

Our model simulations show that for ART to lead to a decline in the HIV prevalence rate, a large enough fraction of the infected needs to be treated (see Figure 3). The reason is that ART affects the prevalence rate through multiple channels:

- ART reduces the transmission risk, which by itself will lower the HIV prevalence.

- ART improves life expectancy once infected, which reduces the incentives to be cautious and thus increases the HIV rate.

- Since those infected live longer, there is more time to infect others, which again increases the HIV rate.

Figure 3 HIV and ART: Model

Our model simulations show that the first effect dominates only once at least 50% of the infected are treated. For lower levels of treatment, the other effects dominate, and HIV might in fact increase.

The impact of policy: Behavioural adjustments and equilibrium effects

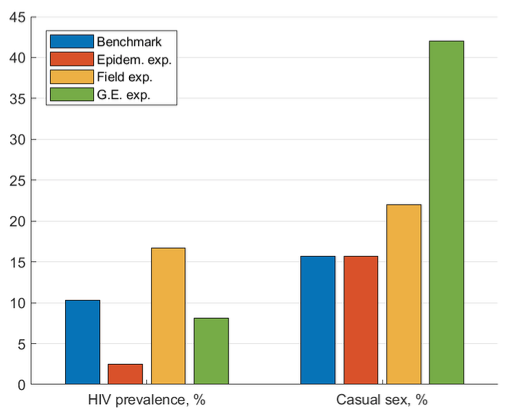

Figure 4 illustrates what would happen if either behavioural adjustments or equilibrium effects were ignored in an experiment where 80% of the infected have access to ART. That is, assume one conducts an epidemiological simulation, i.e. an experiment where one takes equilibrium effects into account but ignores behavioural adjustments to the introduction of ART. Epidemiological disease-transmission literature typically ignores behavioural adjustments (Hethcote 2000).

We simulate this in the model using the red bars in Figure 4. By construction, risky behaviour does not change at all. In particular, casual sex stays constant, as well as the use of condoms, and the decision to marry or stay single.

Figure 4 ART: Full model vs epidemiological vs small field experiment

Ignoring the behavioural adjustments leads to an extreme over-prediction of the success of the policy. Figure 4 shows that one would conclude that the HIV rate would fall to about 2.5%, compared to a much more modest decline to 8.1% predicted by the full general equilibrium model. Thus, policy recommendations that are solely based on epidemiological studies should be interpreted with caution.

Alternatively, assume one conducted a small-scale field experiment where only a small fraction of the population was treated. Field experiments take behavioural adjustments into account. However, since applied to only a small fraction of the population, equilibrium effects are absent. Our simulations show that in such a scenario one would vastly underestimate the effectiveness of the policy. Behavioural adjustments alone lead to an increase in the HIV rate to 17% (see the yellow bars in Figure 4).

In the field experiment, people realise that once they are infected they have an 80% chance of getting treated eventually (7.5% per period) but they still have sex with the general population. In essence, none of their potential partners is treated. Consequently, their behavioural adjustments lead to a very high HIV rate of 17%, with no offsetting effect created by a lower chance of catching the virus. This shows that extrapolating from a field experiment to the general population is problematic.

The importance of information campaigns

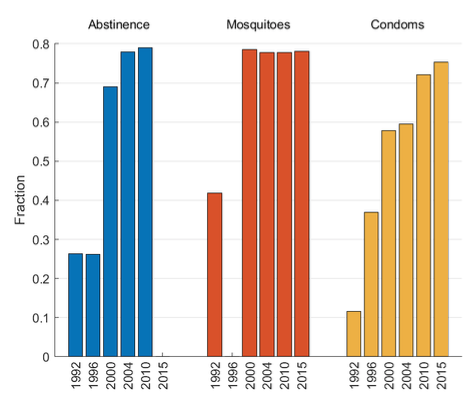

Finally, come back to the question of what can explain the (partial) success of Malawi. One hypothesis worth exploring is to what extent better information about the virus led to the decline in HIV. Survey evidence from the DHS shows a dramatic improvement in HIV knowledge in Malawi since 1992.

Figure 5 illustrates that in 1992 only a quarter of the population correctly identified that abstinence reduces HIV risk, only 10% knew that condom use reduces risk, and about 60% erroneously believed that HIV can be transmitted through mosquito bites. In contrast, by 2004 more than three quarters of the population understood that abstinence eliminates risk, 60% understood that condom use reduces risk, and the erroneous belief related to mosquitos was held by only 20% of the population.

Figure 5 HIV awareness in Malawi

Field experiments have shown that improved HIV knowledge does indeed lead to more cautious behaviour (Dupas 2011). To investigate the hypothesis that improved information led to the observed HIV decline, we add a fraction of misinformed people to the model. The misinformed in the model believe that their infection risk is the same whether engaging in risky behaviour or not. This belief leads them to engage in more risky behaviour.

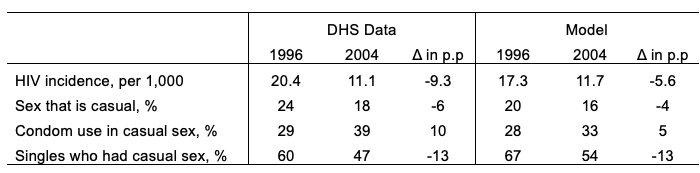

We then simulate a version of the model where 60% of the population is misinformed (representing 1996) and compare it to a version where everyone is informed (representing 2004). As Table 1 shows, once more people are fully informed, risky behaviour decreases along all dimensions: Condom use increases, casual sex declines, and most notably, the fraction of singles engaging in casual sex falls.

Table 1 Improved information in Malawi: DHS data vs model

The simulated orders of magnitude reflect what happened in Malawi over the same time span (based on the DHS survey evidence). This decline in risky behaviour leads to a predicted fall in the HIV rate of 5.6 percentage points. The fall in the data was even larger (9.3 percentage points), leaving room for other policies to have also contributed to Malawi’s success.

Conclusion: Knowledge is power

Despite more than two decades of efforts in fighting HIV/AIDS, almost 40 million people live with the virus worldwide. There is no consensus as to what the most effective prevention policies are. Our work shows that the introduction of ART, while obviously beneficial for those who access the treatment, was probably not a main driver in the recent decline in HIV/AIDS prevalence. Rather the spread of HIV knowledge likely played a large role.

Policy implications

- Knowledge about HIV is widespread by now, so there is little room to further reduce HIV through additional information campaigns.

- Given that ART is at high levels in many countries, further expanding it should have beneficial effects.

- Cultural change through family policy might be a possibility worth considering. If one could promote marriage and dissuade divorce, our simulations show that this would substantially lower the HIV/AIDS rate (Greenwood et al. 2017).

References

Pascaline, D (2011). “Do Teenagers Respond to HIV Risk Information? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(1): 1-36.

Government of Malawi (2015), AIDS Response Progress Report.

Greenwood, J, P Kircher, C Santos and M Tertilt (2019). “An Equilibrium Model of the African HIV/AIDS Epidemic”, Econometrica 87(4): 1081-1113.

Greenwood, J, P Kircher, C Santos and M Tertilt (2017). “The Role of Marriage in Fighting HIV: A Quantitative Illustration for Malawi”, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 107(5): 158-162.

Hethcote, H W (2000). “The Mathematics of Infectious Diseases”, SIAM Review 42(4): 599-653.

Kremer, M (1996). “Integrating Behavioral Choice into Epidemiological Models of AIDS”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111(2): 549-573.

Philipson, T J and R A Posner (1993). Private Choices and Public Health – The AIDS Epidemic in an Economic Perspective, Harvard University Press.

UNAIDS (2018). Miles to Go – Closing Gaps, Breaking Barriers, Righting Injustices, Technical Report, UNAIDS.