When unpopular anti-congestion policies were abandoned in Indonesia's capital, we discovered flawed policy had been better than no policy

Traffic congestion plagues urban life. It frustrates individuals, shortens workdays, and damages the environment and the health of people, as all those stationary vehicles are still emitting exhaust fumes.

Rich countries have the infrastructure to respond with policies that reduce congestion and place the costs onto those who benefit. For example, since 2003 London has implemented a congestion charge, to the general satisfaction of citizens, policymakers and analysts alike. Similar 'smart' policies promise to become even smarter. In 2020, Singapore will begin using GPS technology to base congestion charging on the distance, time, and location of the journey.

Not all policies are created equal

Technological advances may eventually bring smart congestion taxing to developing countries, but until then they will be stuck with blunter methods that have questionable effects. Mexico City banned drivers from using their vehicles one day per week based on the last digit of their license plate, but a study found that it incentivised households to buy more cars, and had no effect on air quality (Davis 2008). Delhi experimented with an 'odd-even' policy that banned car use on certain days based on license plate numbers, but most drivers switched to other private vehicles or found other ways to get around the rule (Kreindler 2016). Vendors sold old license plates to motorists so they could fix them to their cars on days that they would be prevented from driving.

Entrepreneurs selling used license plates near Green Park metro station during Delhi’s 'odd-even' traffic restriction policy, 6 January 2016. Photo: Vestal McIntyre.

Jakarta may have the worst gridlock in the world (Greenfield 2015). It implemented a rule in 1992 that between 7am and 10am, and 4:30pm and 7pm, private cars driving on the main roads of Jakarta's central business district must contain three or more passengers.

The three-in-one policy faced a number of obstacles. Drivers disliked it – as drivers worldwide dislike restrictions – and it did little to ease the city’s congestion (Mochtar and Hino 2006). An informal business sprung up for professional passengers called 'jockeys'. They would stand near three-in-one access points and serve as an additional passenger for around 15,000 rupiah ($1.20). A single driver could hire a mother and child to reach the required number of passengers (Tambun et al. 2012).

The question Jakarta and the world’s other developing supercities face is whether roughly hewn congestion policies work, or if the dissatisfaction the policies sew and gaming they inspire mean they are not worth the trouble.

Policy rollback in Jakarta

In March 2016, the Indonesian government made the surprise announcement that it was suspending three-in-one. Rema and her co-authors Benjamin Olken and Gabriel Kreindler, both of MIT, set out to study the effects of this policy rollback using an inventive new data source (Hanna et al. 2017). They captured real-time, crowd-sourced traffic data for each route by querying the Google Maps application programming interface (API) every 10 minutes, 24 hours a day. The team started to collect data before the suspension went into effect and continued until June. The government permanently scrapped the policy in May.

The reduction in driving speed – a reflection of increased gridlock – was dramatic. After three-in-one was suspended, average speeds went from 28 to 19 km/hour in the morning rush hour, and from 21 to 11 km/hour in the evening rush hour. This implies that Jakarta’s policy had reduced congestion more than London’s congestion charge (decrease in delay of 0.6 min/km according to Transport for London 2006) or Delhi’s Odd-Even experiment (around 0.2 min/km according to Kreindler 2016). This finding also suggests that any increase in traffic due to the jockey system had been negligible.

The increase in congestion when the policy was scrapped was not confined to the morning and evening hours when three-in-one had been in effect, but spilled over onto previously unregulated times. If we focus on travel-time increases, rather than speed decreases, traffic delays increased by 2.0 min/km (55%) during the hour immediately after the evening rush hour, and by 0.55 min/km during the mid-day period, neither of which had previously been restricted.

We would expect the end of three-in-one to reduce traffic on other routes, as motorists return to the previously regulated main thoroughfares. But, surprisingly, ending the policy also created delays on previously unregulated roads. Delays on the main alternate route increased by about 0.60 min/km (14%) during the evening commute.

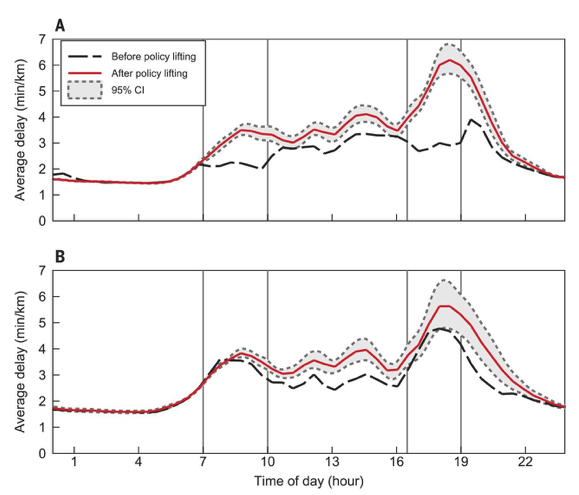

Figure 1 shows these findings. The dashed line in panel A shows delays for a road that was subject to three-in-one restrictions between the time that the policy suspension was announced and when the policy was actually suspended. The red line in panel A shows delays roughly a month after the suspension. Panel B shows similar delays on an alternative route that hadn’t been restricted by the policy.

Figure 1 Traffic delay, before and after congestion policy lifted

Source: Hanna et al. (2017).

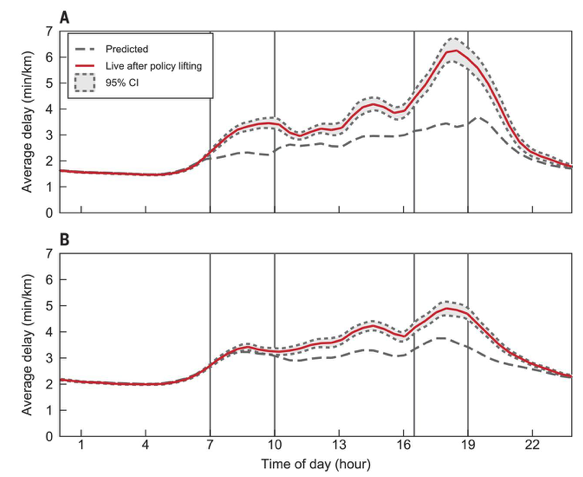

Over time, drivers adjusted behaviour in response to the lifted restrictions. Rema and her co-authors did not have pre-suspension data for these routes, so they compared real delays against Google’s predictions of driver speed. These predictions use all Google’s data on average road speeds. Figure 2 compares real against predicted delays for the expanded set of three-in-one restricted routes in panel A, and alternative routes in panel B, between 28 April (nearly a month after suspension) and 3 June. In this window, the evening rush hour delay was nearly 70% higher than the predicted delay, and there was an increase in traffic in the non-rush hour times of the former restricted roads, and an increase in traffic on the alternate routes.

Figure 2 Traffic delay adjustment after congestion policy lifted

Source: Hanna et al. (2017).

A flawed policy may be better than no policy

We experienced the long-term effects of the rollback of three-in-one at first hand. In August, a trip from Grand Indonesia to Plaza Senayan – a journey of about 5km through central Jakarta – took 50 minutes on foot, and roughly the same amount of time in a car.

While there are a few possible channels for the effects, the most likely one is that eliminating restrictions incentivised more people were induced to drive. They used the roads during peak hours, but also at other times of day.

This study shows how sometimes even a flawed and unpopular policy can improve quality of life. High-occupancy vehicle restrictions can work, and should be a viable option for gridlocked cities in developing countries.

References

Davis, LW (2008), “The effect of driving restrictions on air quality in Mexico City”, Journal of Political Economy 116(1): 38–81.

The Economist (2017), “How and Why Road Pricing Will Happen”, Print edition, 7 August.

Greenfield, C (2015), “Expect delays: world's-worst Jakarta traffic in gridlock for another decade”, Reuters, 17 April.

Hanna, R, G Kreindler, and B A Olken (2017), “Citywide effects of high-occupancy vehicle restrictions: Evidence from “three-in-one” in Jakarta”, Science 357(6346): 89–93.

Tambun, L T, A Saputra, and F Novialita (2012), “Jakarta Jockeys Feel the Squeeze as 3-in-1 Scheme Runs Out of Gas”, Jakarta Globe, 21 October.

Kreindler, G (2016), “Driving Delhi? Behavioural Responses to Driving Restrictions”, Working Paper.

Mochtar, M Z and Y Hino (2006), “Principal issues to improve the urban transport problems in Jakarta”, Memoirs of the Faculty of Engineering, Osaka City University 47: 31–38.

Transport for London (2006), Central London Congestion charging, Impacts monitoring, Fourth Annual Report.