Judicial reforms funded by foreign agencies increase firm productivity, but only in specific sectors where contract enforcement is more important

The judiciary, by enforcing contracts and securing property rights, can foster investment and drive economic development (North 1990, Djankov 2003, Acemoglu 2013). As a result, judicial reforms are often seen as a core component of any development strategy. In my study (Chemon 2018), I find that a total of $5.4 billion has been spent by various foreign aid agencies on judicial reforms since 1996. Yet, there has been no rigorous impact evaluation of these costly interventions.

Legal and academic scholars lament the lack of causal evidence for judicial reforms, or for the judiciary in general (Trebilcock 2009: 65, Aboal 2014). Identifying the causal impact of judiciaries on economic development is extremely difficult due to endogeneity issues, such as reverse causality (rich countries can afford better judiciaries) or omitted variable bias (more fundamental unobserved factors may drive both improved judiciaries and economic development).

Evaluating how judicial reforms affect firm productivity

Mine is the first study to systematically evaluate how judicial reforms, funded by foreign aid, impact firm productivity within countries. My analysis is based on the implementation of judicial reforms in some countries and not others, and on the varying dependence of some sectors on the judiciary for technological reasons.

I assemble and codify a world database of 4,568 judicial projects implemented by 500 foreign aid agencies (governments, multilateral agencies, or private sector organisations) since 1996. This delivers a rich dataset of projects, which vary in budget size, targeted at improving the judiciary's quality, and/or speed, and/or accessibility. For example, in Kenya, the $120 million World Bank Judicial Performance Improvement Project (JPIP) provided support to train court officials and streamline procedures (quality), to introduce performance management contracts designed to reduce the backlog of cases (speed), and to build courts (access). I combine this dataset of judicial reforms with the recent release of a second wave of World Bank Enterprise Surveys for 74 countries. These surveys are ideal for studying the impact of judicial reforms because they contain firm-level data on perceptions of judicial efficiency and firm productivity.

Isolating the effect of judicial reforms

Comparing the evolution of firms in countries with or without judicial reforms may not isolate the causal impact of the reforms. For instance, imagine judicial reforms were implemented by reform-minded leaders who were likely implementing other reforms that positively affecting firm productivity. Our framework would therefore be capturing a general positive trend and not the effect of judicial reforms, per se.

To overcome this problem, I use a well-established insight in economics: some sectors rely more on the judiciary than others because of the need for relationship-specific investments (Klein 1978, Nunn 2007, Levchenko 2007, Amirapu 2015). Consider a buyer asking a seller to produce a customised good. Once this good is produced, the buyer can renegotiate prices down since there is no other buyer for this good. Anticipating this, the seller does not enter this relationship. No customised goods are produced, and the economy is trapped in the production of generic goods to avoid this issue. One solution to this dilemma is to uphold contracts, via third party enforcement. Therefore, sectors that require relationship-specific investments may be particularly dependent on well-functioning judiciaries.

Based on this insight, I compare firms (1) in countries with or without judicial reforms, (2) before and after the reforms, and (3) in sectors more or less affected by judiciaries.

Judicial reforms funded by foreign agencies improve firm productivity only in certain sectors

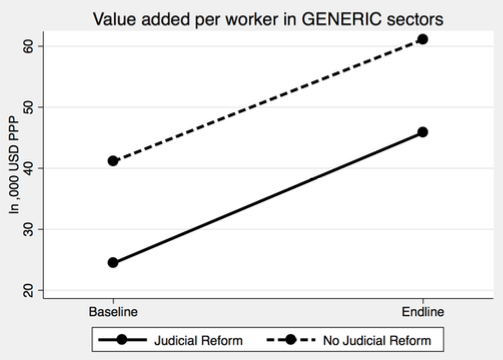

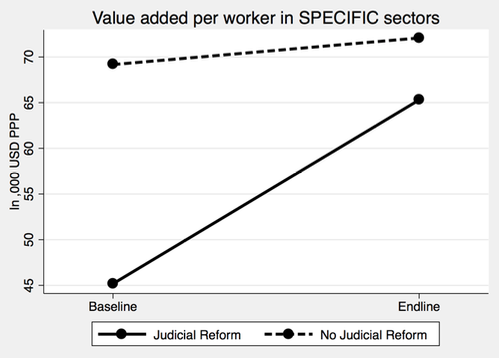

Figure 1 presents my results. Panel (a) shows that in generic sectors, judicial reforms did not have an effect on firm productivity. By contrast, panel (b) shows that judicial reforms, funded by foreign aid agencies, improve firm productivity in sectors relying on relationship-specific investments. I find that these effects are driven mainly by comprehensive judicial reforms, defined as reforms which simultaneously target the three characteristics of a well-functioning judiciary: quality, speed, and access. These reforms also have a project budget over 5% of the judiciary's annual budget, for a given country, which is the average budget of World Bank and USAID judicial reforms, the two “largest and most influential rule of law actors” according to legal scholars (Humphreys 2010: 20).

Figure 1 Effect of judicial reforms on labour productivity

(a) Sectors less dependent on the judiciary

(b) Sectors more dependent on the judiciary

Notes: Labour productivity is value added per worker, expressed in thousands of dollars US dollars PPP. Judicial reform countries are countries in which at least one comprehensive judicial reform (targeting access, speed, and quality, and a budget above 5% of the annual judiciary's budget) was implemented in the period between two enterprise surveys. Sectors less dependent on the judiciary are sectors dealing with generic goods, where the seller could find numerous alternative buyers. Sectors more dependent on the judiciary are sectors dealing with specific goods (goods are specific if it would take more than a month for the main customer to find the same good were the seller to shut down its operations). See (Chemin 2018) for more details.

In contrast, I find no effect of more limited reforms, defined as reforms that address some but not all three characteristics, or with a small budget. My results remain similar when controlling for the overall business climate, the amount of foreign aid received, and other foreign aid projects implemented at the same time.

Policy implications: Judiciary important for development of a modern economy

My findings contribute to the debate about the importance of the judiciary in the process of economic growth. On one hand, North (1990) argues that “the inability of societies to develop effective, low cost enforcement of contracts is the most important source of both historical stagnation and contemporary underdevelopment”. On the other hand, it is easy to think of alternative arrangements to avoid the adverse effects of weak contracting institutions (Acemoglu 2005, Greif 1993).

I provide support for both views articulated around the need for relationship-specific investments. If the output is generic, with many potential buyers, then a seller can circumvent the issue of ex-post renegotiation by turning to other buyers. In this case, the judiciary may matter less. I find empirical support for this in the data: judicial reforms have no significant effect on the productivity of firms dealing in generic goods.

In contrast, if the output is specific with only one buyer, then a seller has no way to avoid the ex-post renegotiation by that one buyer. In such a case, the judiciary is more important. I find support for this in the data: judicial reforms have a large positive effect on firms dealing in specific goods. In conclusion, the judiciary may be less important for generic goods, but is crucial for the emergence of more specific and complex goods i.e. the development of a modern economy.

A further important implication for practitioners is that comprehensive reforms – i.e. those targeting all characteristics at once (quality, speed, and access) and with a budget size above 5% of a country's judiciary – affect firm productivity. In contrast, limited reforms – i.e. those which do not target all characteristics at once or with a small budget – have no effects. The intuition is that increasing access to an otherwise slow and corrupt judiciary, does not fundamentally affect outcomes. Therefore, comprehensive rather than limited judicial reforms should be favoured.

References

Aboal, D, N Noya and A Rius (2014), “Contract enforcement and investment: A systematic review of the evidence”, World Development, 64: 322–338.

Acemoglu, D and J Robinson (2013), Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty, Crown Business.

Acemoglu, D and S Johnson (2005), “Unbundling institutions”, Journal of Political Economy, 113(5): 949–995.

Amirapu, A (2015), “Judicial institutions, relationship specificity and growth: Evidence from India.”

Carothers, T (2003), Promoting the rule of law abroad: The problem of knowledge, Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Chemin, M (2018), “Judicial efficiency and firm productivity: Evidence from a world database of judicial reforms”, Review of Economics and Statistics.

Djankov, S, R La Porta, F Lopez-de Silanes and A Shleifer (2003), “Courts”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(2): 453–517.

Greif, A (1993), “Contract enforceability and economic institutions in early trade: The Maghribi Traders’ Coalition”, The American Economic Review, 525–548.

Humphreys, S (2010), The art of the rule of law: Transnational legal intervention in theory and practice, 73, Cambridge University Press.

Klein, B, R Crawford and A Alchian (1978), “Vertical integration, appropriable rents, and the competitive contracting process”, The Journal of Law and Economics, 21(2): 297–326.

Levchenko, A (2007), “Institutional quality and international trade”, The Review of Economic Studies, 74(3): 791–819.

North, D (1990), Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press.

Nunn, N (2007), “Relationship-specificity, incomplete contracts, and the pattern of trade”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2): 569–600.

Trebilcock, M and R Daniels (2009), Rule of law reform and development: Charting the fragile path of progress, Edward Elgar Publishing.