An experiment shows that public servants make errors when interpreting data, incorrectly concluding that it aligns with their ideological preferences

One of the most difficult challenges for promoting evidence-based policy is that politicians tend to have predetermined views of the world, often tainted by ideology. Recently, I finished a six-year spell as a UK civil servant, as chief economist of DFID, the UK government department responsible for international development policy and spending. UK civil servants have a strict code that stipulates that while they are serving and accountable to the political leadership of the country, they should also be impartial and make judgements based on the best evidence available, and not preconceived ideas. In my experience, the UK civil service code is not loose talk – it is taken very seriously by civil servants and politicians.

Implicit biases

Still, to what extent are these public officials affected by preconceived ideas rather than impartial evidence? We know from behavioural science that people are strongly affected by confirmation bias, the tendency to seek out information that confirms one’s prior beliefs (Nickerson 1998). Does it affect public officials’ ability to make judgements based on evidence? My co-authors and I set out to test this and other biases amongst a large sample (n=2778) of World Bank and DFID officials (Banuri et al. 2017). World Bank officials are similarly expected to make judgements based on high quality technical analysis.

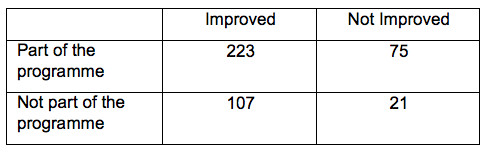

We gave our entire sample a version of the following table, reminiscent of some impact evaluation.

Table 1 Example impact evaluation

We told the respondents that this was the evidence from a good quality impact evaluation, and we asked them to tell us what the evidence told them about the impact of the programme – did it work in terms of improving outcomes or not? Each got a version of this table, but we randomised the order of the rows and columns. Furthermore, and most importantly, we randomised the framing. One group was told that this was the evidence on skin cream and the impact on a rash. Another group was told that this was evidence of income changes of the poorest 40% when the minimum wage was increased in the local area.

Results

The results were striking. Our design intention was that the skin cream framing was ‘neutral’ in that there was little reason to suspect that subjects held prior views. We found that 65% of the sample faced with that framing gave the right answer, with no statistical difference between the World Bank and DFID. Obviously, a cause of concern if we care about the numeracy of these officials, but that was not the most notable finding. Among those randomly selected to receive the minimum wage framing, the percentage of correct answers drops to 45%.

It gets worse. Elsewhere in the survey, we elicited respondents’ views on preference inequality, based on a 1-10 scale, where 1 indicated “Incomes should be made more equal”, and 10 that “We need larger difference as incentives for individual effort”. We find a strong correlation between the direction of the error and people’s preferences for inequality. Those faced with evidence of a successful (failing) programme for the poor’s incomes were more likely to make errors if they believed inequality was bad (good). There is no such relationship in the case of the skin cream framing. There were never any differences between DFID and the World Bank in these results. In short, public officials in both institutions show some confirmation bias, linked to their own ideological preferences.

Conclusion

Researchers will not be too surprised by these results, but the size of the sample and their professional roles makes it at least interesting. These results definitely surprised UK civil servants – it showed that even in a simple assessment of data we could show they are not as impartial and evidence-based as they would claim to be. And the ideological bias is not simply due to politicians meddling based on their ideology, but linked to their own preferences.

To give them credit, a number of teams of government officials have responded by trying to avoid this. The remedy is not a guarantee for a cure, but worth trying. Independent peer review within departments, such as via an independent ‘quality assurance unit’ as in DFID, surely will play a role. Red teaming, in which one person in a team is expected to find all arguments against some proposal, is now also more widely practiced, I am told. But as with most behavioural biases, thinking a bit slower, taking stock, questioning one’s priors and showing some humility is a good start. This is not just important for public officials entrusted to use evidence for decision making, but all of us, including researchers. By the way, when did you last change your mind due to a piece of research or evidence?

References

Banuri, S, S Dercon and V Gauri (2017), “Biased policy professionals”, World Bank Group, Policy Research working paper no WPS 8113.

Nickerson, R S (1998), “Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises”, Review of General Psychology 2(2): 175.