Evidence from the Jobs of the World Project shows that as countries develop they undergo three broad transformations in the organisation of labour: the marketisation of work, the emergence of wage work, and the fractionalisation of labour into specialised occupations

Economic growth is accompanied by profound transformations in the organisation of labour – that is the nature and allocation of jobs. The most well know transformation is the move of labour from agriculture into manufacturing and services (Herrendorf et al. 2014). Other aspects of the changing nature of work are less well studied. For example, a shift from household subsistence to market production introduces gender as an important determinant of work (Boserup 1970, Goldin 1995), and the emergence of large firms moves almost the entire workforce from self-employment into salaried wage work (Gollin 2013, Jensen 2022).

The increasing availability of micro-data provides novel opportunities to study these transformations. In our recent research (Bandiera et al. 2022), we assemble and harmonise a new, publicly available data set and illustrate its use by describing three broad transformations in the organisation of labour over the course of economic development.

The Jobs of the World Database

The Jobs of the World Project is a public resource designed to enable research on jobs and poverty across and within countries over the entire range of economic development. At its core is a new data set assembled by harmonising publicly available data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and National Censuses (IPUMS) for all countries and all years after 1990 where data is available. The current version covers 113 countries, observed 3 times on average.

Harmonisation of the two data sources ensures that different measures of work are defined consistently. We also create a within-country wealth rank based on households’ asset ownership. This allows us to split the working population into different wealth groups.1

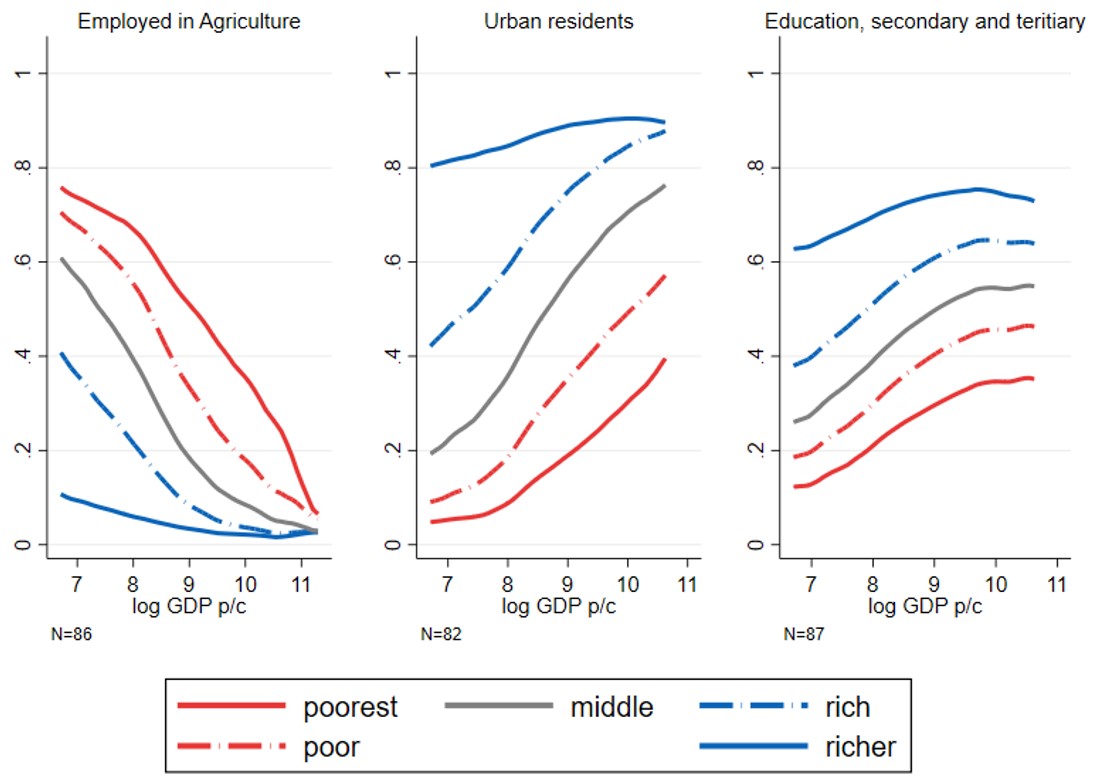

The wealth group and other demographic variables are used to split country aggregates by subgroups of the population. This reveals how different population groups experience major economic transitions very differently. While aggregate growth is associated with employment outside of agriculture, urbanisation and mass education, the cross-country variation is dwarfed by within-country differences across wealth class (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Inequality within and across countries

Three Transformations in the organisation of labour

Using the Jobs of the World Database, we document three broad transformations in the organisation of labour: the marketisation of work, the emergence of wage work, and the fractionalisation of labour into specialised occupations.

We argue that these transformations happen simultaneously with many of the better-known dimensions of economic development such as structural transformation. For each transformation, we use the underlying micro-data to document the role that different population groups play in them, focusing on gender and wealth.

1. Marketisation

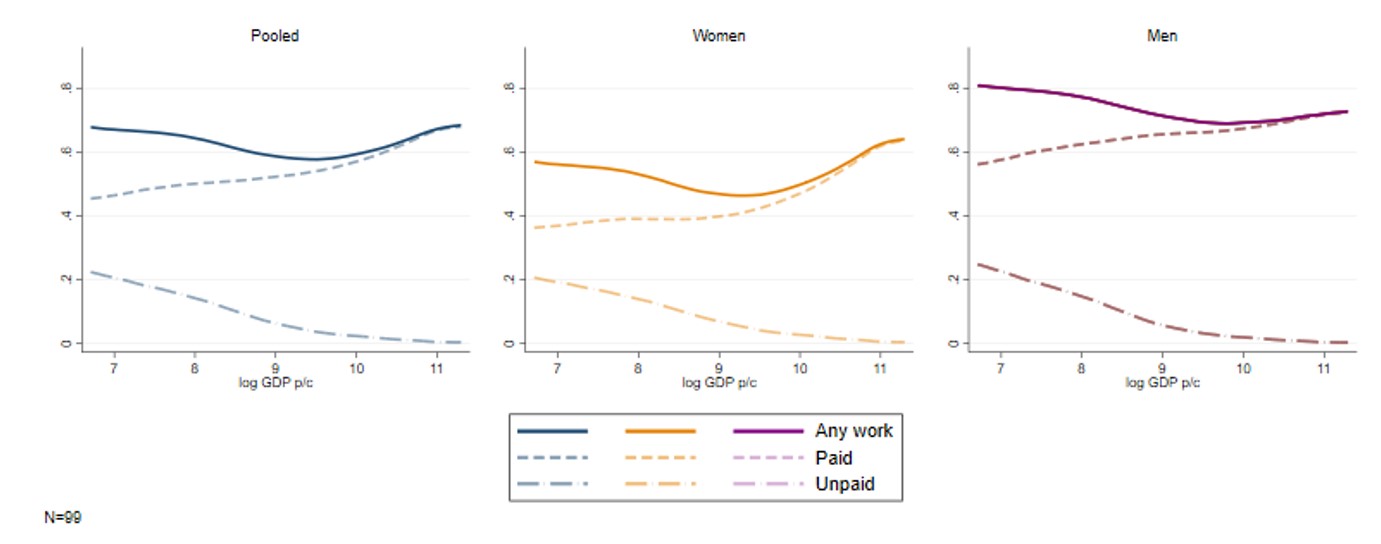

The marketisation of work occurs as labour moves from unpaid work—in the household, a family-farm or -business—to paid work (Figure 2). As countries get richer, an increasing share of output is sold in the market and new jobs—such as carpenters and tailors—become increasingly more common, providing services that were previously integrated in home production (Boserup 1970).

The shift from home to markets coincides with the rise of gender and wealth as determinants of the allocation of labour. Measures of unpaid work are similar for men and women, but women report less paid work, especially in low- and middle- income countries (Figure 2). The decline in women’s measured work going from low to middle income countries is driven entirely by the decline in unpaid labour (Schultz 1990) and this is what drives the U-shape in overall measured work (Goldin 1995, see also Ngai et al. 2022).

This is most likely explained by mismeasurement rather than women in middle income countries being idle. As households leave unpaid work in agricultural subsistence, men move into paid work (all of which is measured) while women specialise increasingly in home production (which is recorded if producing goods but not services) and thus “disappear” from the measured labour force. We argue that standardised time use surveys are crucial to take accurate account of all types of work.

Figure 2: Paid, unpaid, and total work as a share of the working age population against log GDP per capita

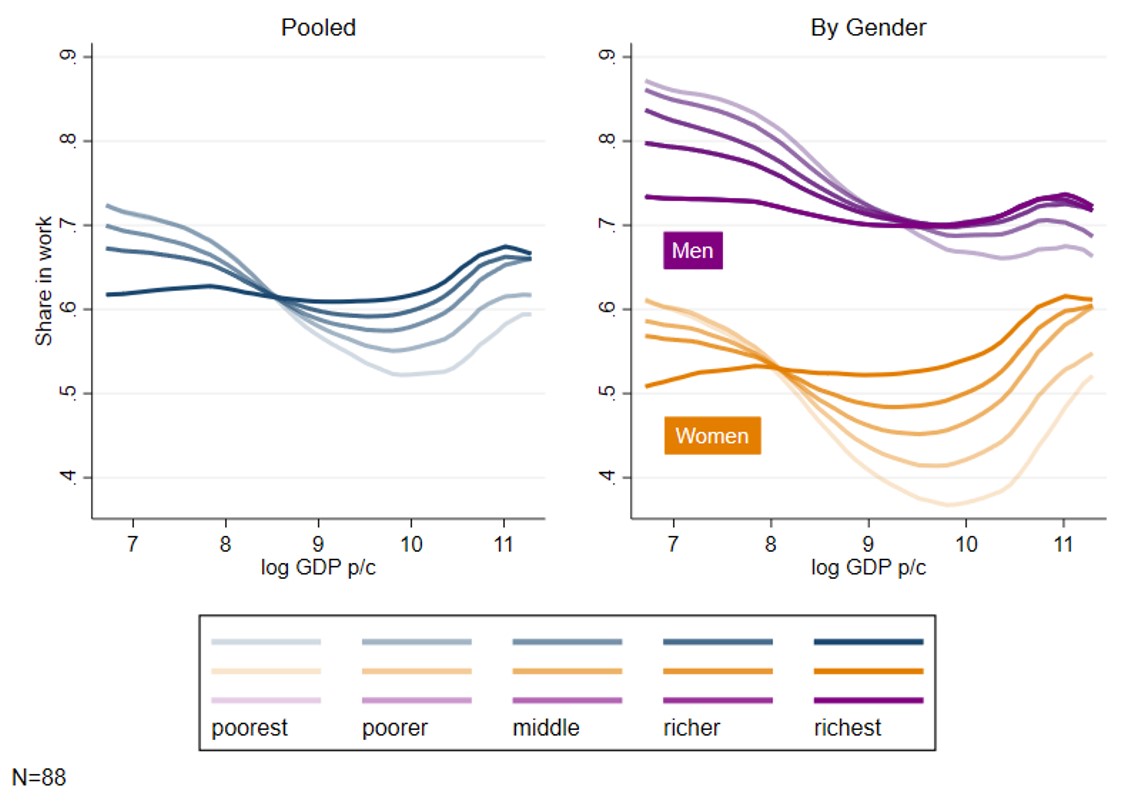

Wealth is a less important predictor of who works than gender, at all levels of national income (Figure 3). But the split by wealth generates an interesting pattern: at low levels of development, the share of people engaged in any measured work is higher in the bottom quintile of the within-country wealth distribution. This is driven by the high share of low-wealth households performing unpaid work. As unpaid work disappears, the ordering by wealth reverses, and the share of people at work is highest in the top quintile.

The U-shape is most prevalent for the poorest women. This casts doubt on explanations according to which the U-shape is driven by an income effect that allows women in middle-income countries to consume more leisure.

Figure 3: All work (paid + unpaid) against log GDP per capita by gender and within-country wealth quintile

2. Wage work

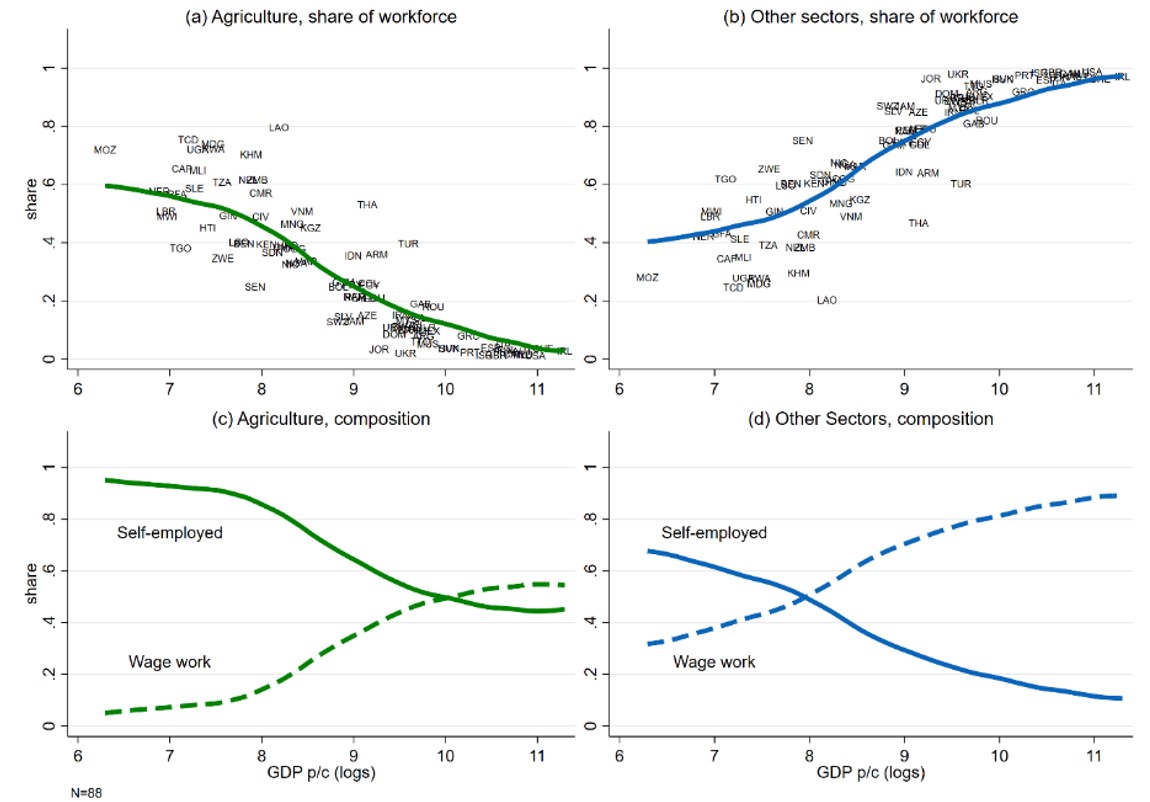

The second transformation in the organisation of labour occurs as self-employed work is replaced by wage work - predominantly salaried employment in firms. The share of workers in wage work increases from 10% in low-income economies to above 90% in the richest countries. The transformation is mostly due to the emergence of firms as the main organising unit of labour. The public sector constitutes a large share of wage work at low levels of national income but after that only accounts for a fraction of the increase in wage work.

The move from self-employment into wage work happens alongside other well-known changes such as urbanisation, education, and structural transformation. For example, the share of wage work is higher in manufacturing and services than in agriculture at all levels of income. But the shift of labour out of agriculture can only partly explain the rise in wage work, which happens within both the agricultural and non-agricultural sector (Figure 4).

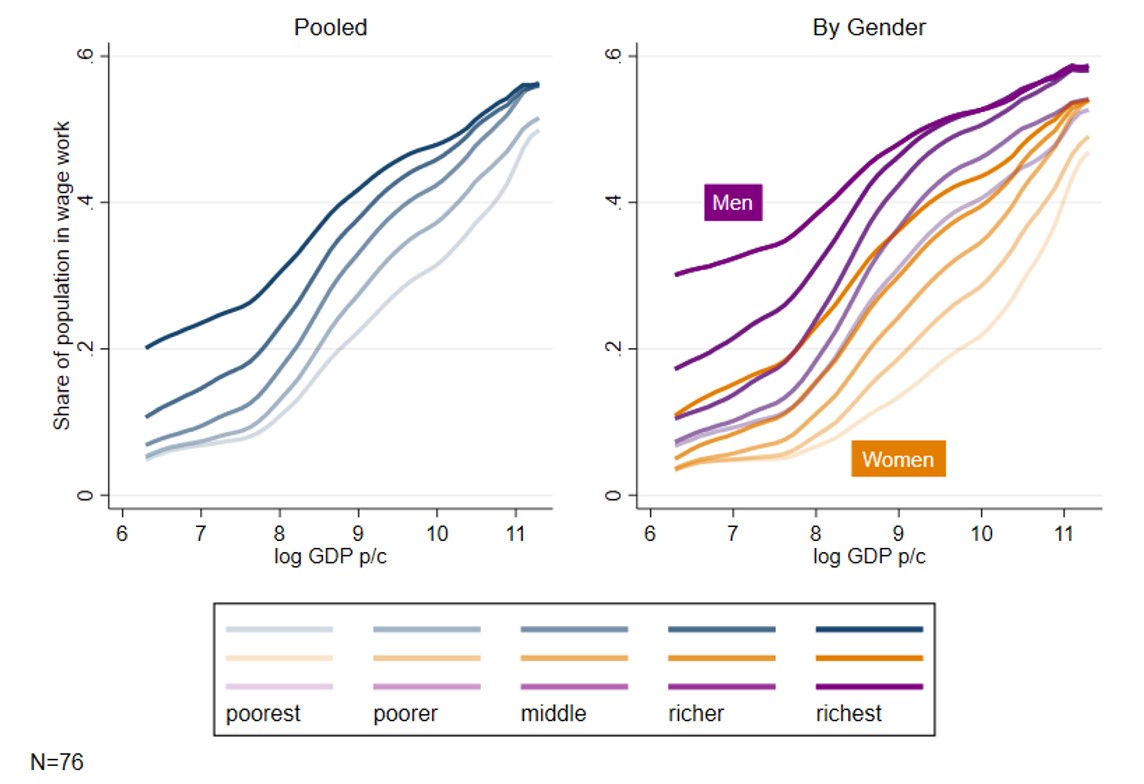

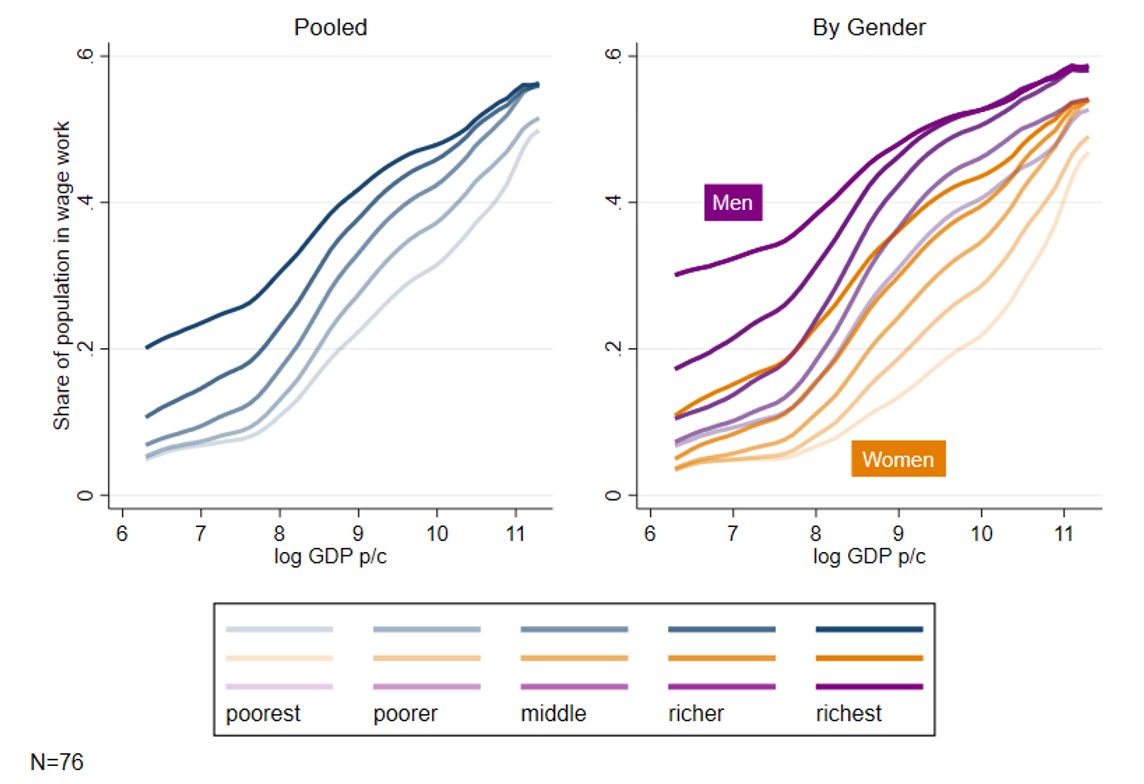

The allocation of salaried jobs also follows wealth and gender lines. It is men from wealthy households that first take up wage work, followed by men of poorer households, and finally women (Figure 5). This feeds into the above narrative whereby the poorest in poor countries are the most likely to work but they work out of necessity and in the worst types of jobs. Both gender and wealth are less predictive of wage work in the richest countries.

Figure 4: Structural transformation and wage work.

Figure 5: Wage work as a share of working age population and wage work in the public sector

3. Specialisation

The third major transformation of work consists in an increase in the variety of different occupations and the resulting specialisation of labour. In places where subsistence agriculture dominates the economy only a handful of different occupations are available, while workers in high-income countries, especially in cities, can choose from hundreds of different occupations (Figure 6).

We further show that the increase of occupational variety is concentrated among wage workers. Presumably, firms use technologies and management practices that allow for a more granular division of labour than what is possible among a dissociated group of self-employed workers. Conversely, more specialised jobs might contribute to productivity gains by facilitating on-the-job training and allowing better matches between tasks and workers’ specific skills and interests.

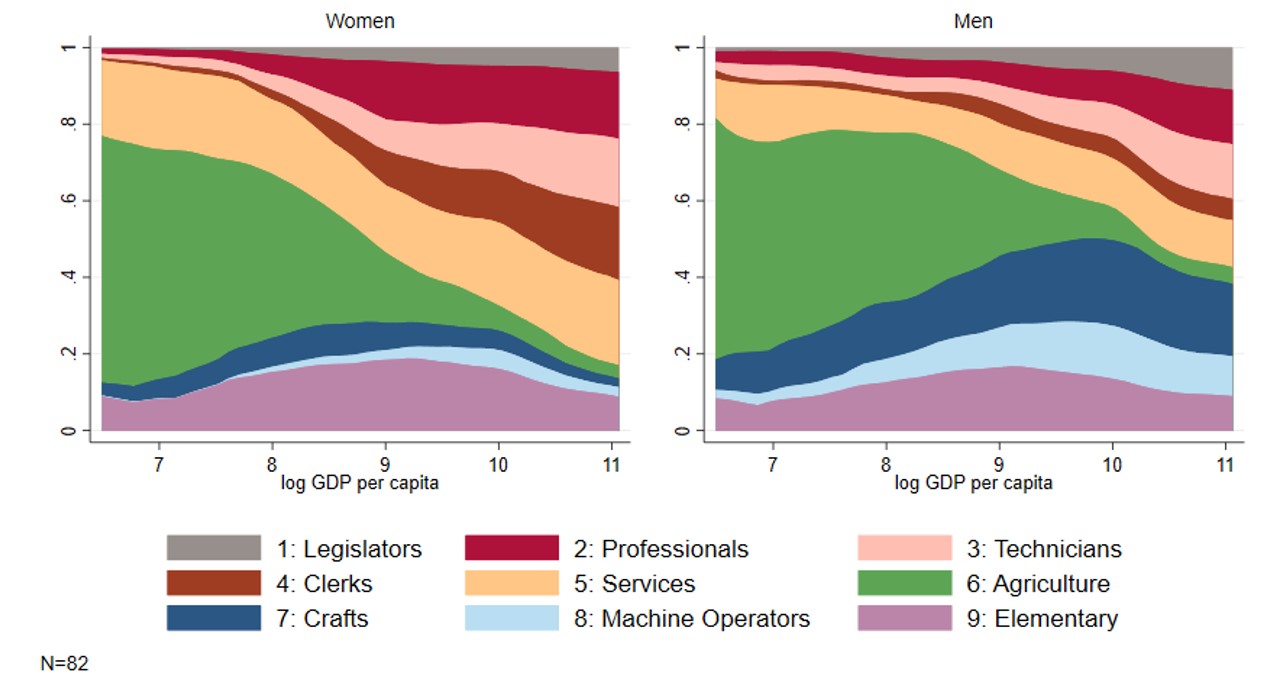

Occupational diversification eventually occurs for both men and women, but the types of occupations they enter differ and labour becomes more strongly gendered (Figure 7). Further, conditional on working, women move increasingly into professional, technical, and clerical service jobs, while men account for increases in the share of crafts, legislators and machine operators. The increase in occupational variety is, hence, accompanied by an increase in occupational segregation by gender. Our research provides additional evidence for this relationship by computing gender segregation across a fine occupational classification.

Figure 6: Variety of Occupations against log GDP per capita

Figure 7: Occupational composition of jobs against log GDP per capita, by gender

Discussion

The descriptive patterns outlined above show that the organisation of labour differs substantially across countries and within them. The differences are systematic: it tends to be women and people in poor households who have access to fewer and worse jobs. We find this pattern everywhere, but it is stronger in poorer countries.

These results justify a focus on the nature and distribution of work, both as a measure of welfare and a policy target.

The role of gender and wealth in the allocation of labour brings to the fore the link between individual poverty at the micro-level and national income at the aggregate. These characteristics are both morally arbitrary and orthogonal to innate ability. Indeed, growing evidence documents that lessening the influence of gender and wealth on access to work can lead to productivity gains (e.g. Bell et al., 2019; Hsieh et al., 2019; Ashraf et al., 2022). We often focus on the effect of growth on poverty reduction, but in light of this evidence the direction of causality might be reversed. Ultimately, when the talent of many is trapped in poverty, eliminating poverty becomes a precondition for economic growth.

References

Ashraf, N, O Bandiera, V Minni, and V Quintas-Martinez (2022), “Gender Roles and the Misallocation of Labour Across Countries.” Working Paper, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Bandiera, O, A Elsayed, A Heil, and A Smurra (2022), "Economic Development and the Organisation of Labour: Evidence from the Jobs of the World Project." Journal of the European Economic Association 20(6): 2226-2270. Link to paper: https://academic.oup.com/jeea/article/20/6/2226/6763595

Bell, A, R Chetty, X Jaravel, N Petkova, and J Van Reenen (2019), “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134: 647–713.

Boserup, E (1970), Woman's role in economic development. London: George Allen & Unwin

Diaz-Pardo, G and A Smurra (2022), “Jobs of the World Project v1.1: User Manual.” Working paper, http://jwp.iza.org, retrieved 13 November 2022.

Goldin, C (1995), The U-Shaped Female Labor Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History. University of Chicago Press, pp. 61–90.

Gollin, D (2008). "Nobody's business but my own: Self-employment and small enterprise in economic development." Journal of Monetary Economics 55(2): 219-233.

Herrendorf, B, R Rogerson, and A Valentinyi (2014) "Growth and structural transformation." Handbook of economic growth 2: 855-941.

Hsieh, C-T, E Hurst, C I Jones, and P J Klenow (2019), “The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth.” Econometrica, 87: 1439–1474.

IPUMS (2020) “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International.” https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.3, retrieved 13 November 2022.

Jensen, A (2022), “Employment structure and the rise of the modern tax system.” American Economic Review, 112(1): 213-234.

Ngai, R, Claudia O, and B Petrongolo (2022), “Structural Transformation over 150 years of Women’s and Men’s Work.”

Schultz, T P (1990), “Women’s Changing Participation in the Labor Force: A World Perspective.” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 38: 457–488.

Footnote:

1 Users of the Jobs of the World Database can introduce analogous splits along many demographic characteristics such as gender, age, and marital status. The data and programmes used to construct the database are available at http://jwp.iza.org. For details see the JWD user manual (Diaz-Pardo and Smurra, 2022). The database is an output from a project funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and the Institute of Labor Economics (IZA) within the G²LM|LIC Programme. The views expressed are not necessarily those of FCDO or IZA.