Long-term results from a cash grant programme in Uganda suggests that poverty may be bigger than the issues these types of programmes can address

Cash transfers have increasingly become popular as tools to promote economic development. Unconditional cash transfers, along with programmes like the BRAC graduation model (Banerjee et al. 2015), largely focus on reducing poverty or other vulnerabilities. Both cash and graduation programming have received significant attention in the research literature because researchers have found large effects on income and consumption.

However, these approaches are relatively micro in their approach. They target a few hundred or thousand people, are run in relatively controlled programming conditions, and researchers test for outcomes after a year or two. Little is known about whether these effects can be scaled and for how long they last (Bougen et al. 2019).

The Youth Opportunities Programme in Uganda

In line with the growing popularity of cash transfers, the Government of Uganda, with financing from the World Bank, launched the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) in 2006. The programme offered cash grants to groups of young adults, approximately aged 18 to 35, for the purpose of starting a small business. Groups of 15 to 30 youths prepared business plans to use the grants for training in skilled enterprises and to purchase tools and materials for their business. The businesses could be run as a group, or individually.

We describe the grant as semi-conditional because the youth had to prepare a proposal. However, after the money was received there was no oversight from the government. This semi-conditionality is likely an important aspect of the programme because, unlike purely unconditional transfers, we find that people generally invested the money into training and materials.

If selected by the government for funding, the money was deposited into a group bank account. The average grant was $7,497 per group, or about $382 for each group member. This was equal to roughly a year’s worth of income for youth in Uganda at the time.

Measuring the long-term impact of the Youth Opportunities Programme

In 2008 the government reviewed and approved 535 group proposals, but only had funding available for 265. We randomised which of the groups received the grant and which would serve as a control. We then followed a random sample of five individuals in each group, for a total of 2,675 individuals. We conducted a baseline survey in early 2008, a first follow-up in mid-2010, a second follow-up four years after the programme in mid-2012, and a third follow-up survey in mid-2017, nine years after the programme (Blattman et al. 2020). Our survey team were able to track 91% of members after two years, 84% after four years, and 87% after nine years.

What was the money used for?

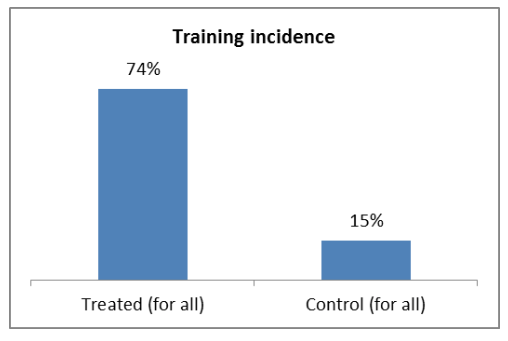

Our first question was whether the youth used the money as they had said they would. During the first follow-up survey, we asked questions on whether an individual received training. As shown in figure 1, we find that 74% of the group that were beneficiaries of the transfer received some kind of skills training, compared to 15% of the control group. However, of those that received training, the length between the two groups was very different. Those in the treatment group received on average 560 hours of training, whilst those in the control only 321 hours.

Figure 1 Training incidence

Comparing short-term and long-term impacts

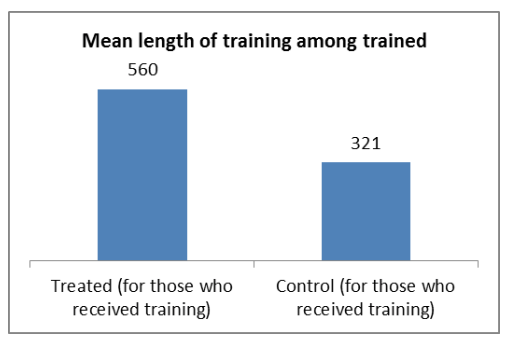

We found strong economic effects from the programme in the two- and four-year follow-ups. Those that received the grant worked 134% more hours in skilled trades compared to those that did not. This led to large increases in income (37% over the control), consumption (10% over control), and assets. These effects were larger for women than men, mostly because control women had very little income growth over this time period.

However, most of these results did not last. By the nine-year follow-up, we find that both the men and women that did not receive the grant had caught up to those that did in terms of income and consumption.

Over time the control group worked identical work hours to the treatment group. Although they worked the same number of hours per week, grant recipients were more than twice as likely to be working primarily in skilled trades as non-recipients nine years after the transfers. However, both groups earned the same average hourly earnings. Figure 2 shows how income changed over time for the treatment and control groups, separated by gender. Even without start-up capital from YOP, individuals in the control group were able to expand their earnings opportunities.

Figure 2 Income changes over time for men and women

Declining income growth

One interesting result from our analysis is that treated individuals did not accelerate their income growth over time. It appears that between the four- and nine-year follow-ups, the treatment individuals actually saw a slowdown in their income growth. While we do not know exactly what caused this to happen, it is very likely that we are observing potential pressures on business owners, perhaps even structural issues that make expanding businesses difficult. Work on how to expand existing enterprises (Fiala 2018), suggests that increasing business income over time is extremely difficult.

But it is not all bad news: YOP was cost-effective

It is important to note that the programme had lasting impacts on household assets, mostly from purchased animals, and a sustained increase in the likelihood of engaging in skilled trade. We also find some evidence of an increase in child health for children born to mothers that received the grant.

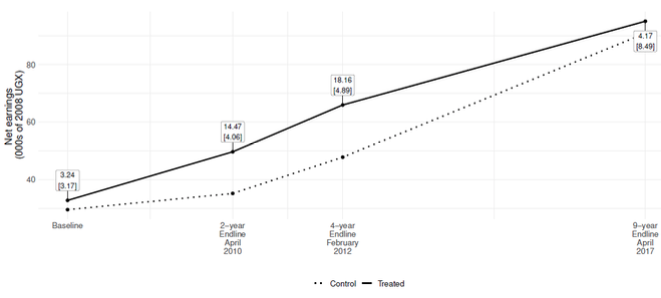

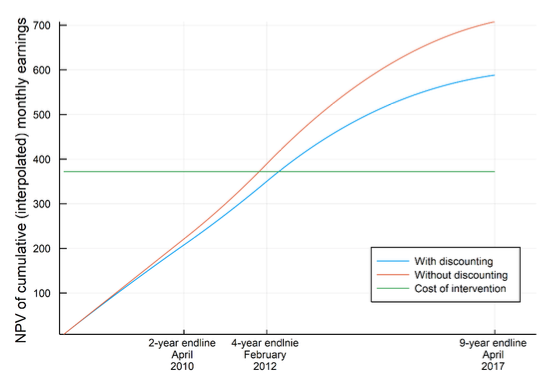

Moreover, a standard cost/benefit analysis, depicted graphically in figure 3, estimates that YOP provided temporary earnings gains of approximately $665 per individual recipient, which is roughly 1.8 times the size of the grant. Therefore, while the long-run results show that the programme was more of a kick-start than a lift out of poverty, it was extremely cost-effective.

Figure 3 Cost benefit analysis of YOP

What works?

Micro programmes do not generally show a decrease in poverty. Similar to our results here, Misha et al. (2014) find that graduation programmes likely only have short-run impacts. Given how extremely expensive the graduation model is (up to $5000 per participant), this is disappointing news.

However, most studies do not look at the long-run impacts of programmes. More evidence is needed on whether the impacts that researchers have found stick around. Longer time frames for data collection will help answer this question (Peters et al. 2016).

Micro programmes like YOP and graduation programmes do help people, at least for a little while. However, these interventions are not the end of the problem, only a stopgap solution. The evidence so far suggests that these types of programmes do not solve poverty, they just make it a little less bad for people.

If micro solutions to poverty are not working, then what does work? The real problem is bigger than what micro programmes can offer. They are the structural issues. These include geography, trade opportunities, governance, infrastructure, norms, institutions, macro-land use decisions and many more things that cannot be randomised, and take a larger, multi-faceted approach to tackle.

References

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, N Goldberg, D Karlan, R Osei, W Parienté, J Shapiro, B Thuysbaert, C Udry (2015), “A multifaceted programme causes lasting programme for the very poor: Evidence from six countries”, Science, 348, 6236.

Blattman, C, N Fiala and S Martinez (2020) “The long-term impacts of grants on poverty: 9-year evidence from Uganda’s Youth Opportunities Program”, forthcoming, American Economic Review: Insights.

Bouguen, Adrien, Yue Huang, Michael Kremer, and Edward Miguel (2019), “Using Randomized Controlled Trials to Estimate Long-Run Impacts in Development Economics”, Annual Review of Economics, 11:523-561.

Fiala, N (2018), “Returns to microcredit, cash grants and training for male and female microentrepreneurs in Uganda”, World Development, 105, 189–200.

Misha, F, W Raza, J Ara and E Van de Poel (2014), “How far does a big push really push? Mitigating ultra-poverty in Bangladesh”, ISS Working Paper, 549, Rotterdam: International Institute of Social Studies.

Peters, Jörg, Jörg Langbein and Gareth Roberts (2016), “Policy evaluation, randomized controlled trials, and external validity—A systematic review”, Economics Letters, 147: 51-54.