Existing disaster aid programmes focus on property owners that experience physical damages. Evidence from Nepal shows that a broader and less targeted approach could be easier to implement and better for welfare.

In April 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck the mountainous regions around Kathmandu in Nepal. This was the largest earthquake in that region since 1934, and it triggered landslides and aftershocks throughout the country. The final death toll was nearly 9,000 people, and an estimated 12% of the country had their homes destroyed (The Asia Foundation 2016).

Aid in Nepal was targeted based on property damages

In the months after the earthquake, a multilateral donor fund pledged $4.1 billion in aid for reconstruction. The aid was targeted at households who suffered severe property damages from the disaster. Teams of engineers travelled around the country drawing up lists of eligible beneficiaries. Households that qualified received 300,000 NPR (about $3,000) to fund reconstruction of their house.

The approach of targeting disaster aid based on property damages is common. In the US, FEMA spends on average more than $1 billion annually on aid to homeowners who suffer housing damages in a disaster. Internationally, shelter makes up the second largest portion of disaster aid funding, after food aid. In disasters in low-income countries, funds earmarked for housing reconstruction are often the only sources of cash aid for households. The relevance of using property damage as a proxy for need is not well established, however. In fact, it has been suggested that this approach to targeting may increase inequality, since it tends to allocate aid to wealthy property owners (Howell and Elliott 2019). Other forms of vulnerability, including barriers to credit and insurance markets, are harder to observe, but may be more important in determining a household’s post-disaster welfare and ability to recover. Yet property damage persists as a criterion for targeting because it is an easily visible mark of a disaster’s effects.

Property damages can be a misleading proxy for need

In Gordon, Hashida and Fenichel (2024), we study the question of how to target aid after a disaster, using the 2015 Nepal earthquake as a case study. We find that property damages are a misleading proxy for need. We create a model of household demand for aid based on survey data of households after the earthquake, and we find that making aid conditional on property damage is no better than allocating it randomly. If aid had been perfectly targeted at the households sustaining the largest property damages, this would not have increased welfare relative to an allocation where recipient households are chosen at random. In contrast, an untargeted approach that divided the same amount of aid evenly among all households in the affected areas would have increased total household surplus by 12%.

Household demand for aid does not correlate well with property damages for two reasons. First, some households that experienced damages have ‘insurance’ – access to loans and remittances that allow them to recover regardless of whether they receive aid. Second, some households have no property damage, but they still have high value for aid in order to meet their immediate needs.

Spreading a smaller amount of aid across more households generates more welfare than targeting larger amounts of aid at fewer households – especially when the targeting is based on poor proxies. This implies that collecting better data on household damages to inform aid distribution may not be cost effective.

How was disaster aid used in Nepal?

In order to inform our model of household value for aid, we study the ways in which households spent disaster aid. Of course, households that received aid are different from households that didn’t in many ways – in particular they are much more likely to have experienced property damages from the earthquake.

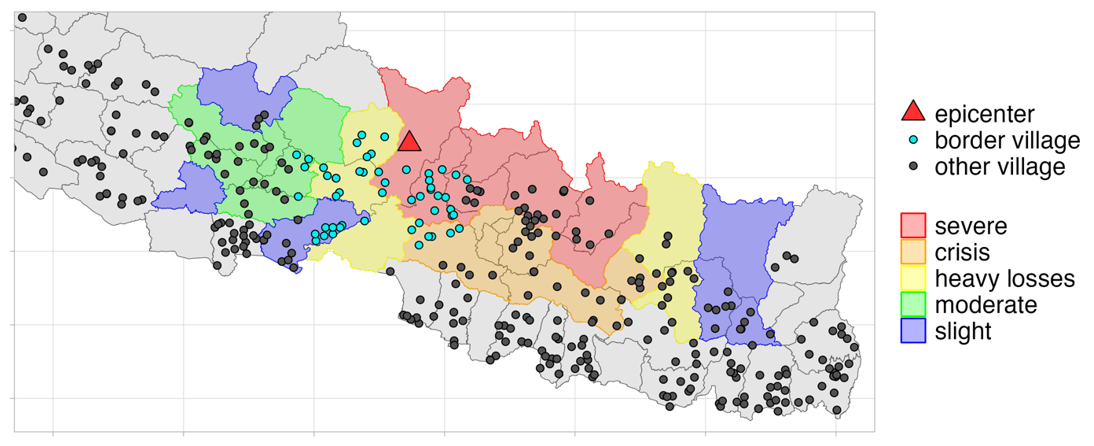

To study the effects of aid, we rely on an administrative feature of the reconstruction program. The earliest tranches of aid were focused on the hardest hit districts, the red and orange districts in the map in Figure 1. Households close to the borders of those districts experienced similar levels of earthquake damages, but differed in the probability of receiving aid, with households in the red and orange districts about 25% more likely to receive aid.

Figure 1: Map of the study area

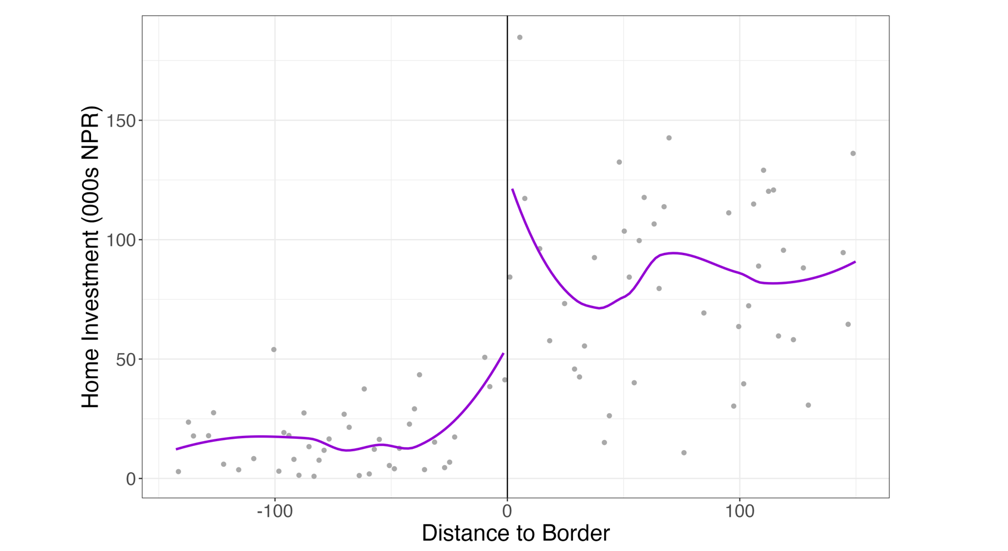

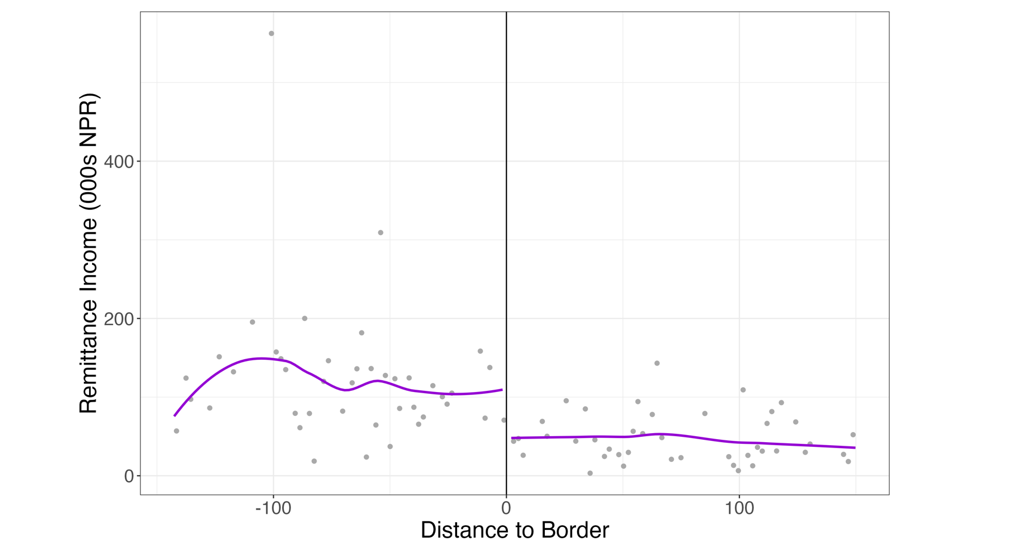

Restricting our analysis to households within about 60 km from the border on either side (represented by blue dots in the map in Figure 1), we estimate the effect of aid by looking at whether variables of interest change at the border. In the first part of Figure 2, we see that households on the eastern side of the border have much higher housing investment, suggesting that they used the aid to rebuild their homes. However, the second part of Figure 2 shows that households that received aid were less likely to receive remittances. Since remittances are a common form of informal insurance in Nepal, this suggests that some of these households substituted aid for other forms of informal insurance.

Figure 2: Estimates of the effect of aid on housing investment and remittances

We use these results to inform a model of household demand for reconstruction aid, where households differ in their earthquake damages and access to forms of informal insurance.

How should we target disaster aid?

The question of how to target disaster aid is complicated, and depends on the purpose of the aid. We assume that the planner wants to use the aid as a form of social insurance – they want to help households smooth consumption and alleviate some of the temporary distress created by the shock. Consistent with this idea, we measure welfare as how much future income a household would be willing to give up, in exchange for receiving aid in the present. We also think about alternative goals, helping the poorest households, improving food security, and facilitating housing reconstruction.

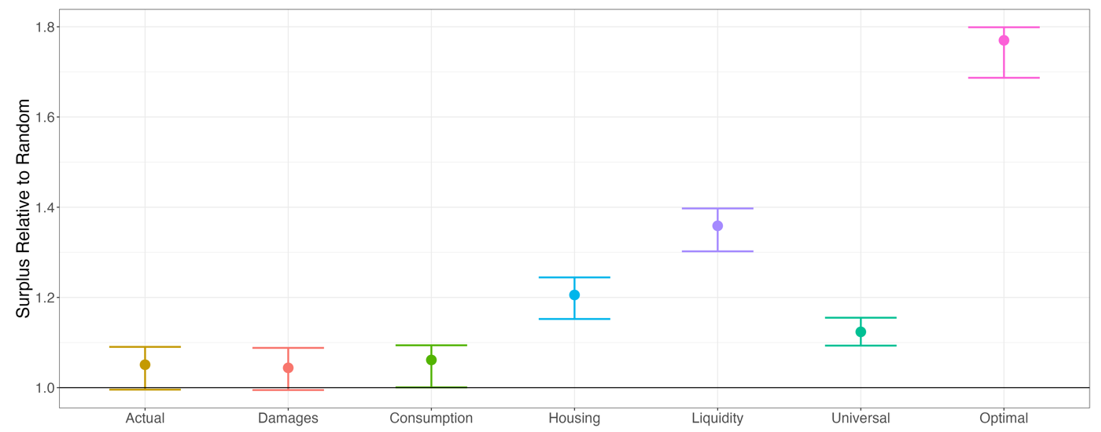

As a benchmark, we evaluate all allocations of aid relative to a completely random allocation – as if the aid was not targeted at all. In all allocations the amount of aid (300,000 NPR) and the number of households receiving aid (38% of the affected districts) are held constant, except for the universal allocation, which holds the total budget constant, but gives all households a smaller amount of aid. The welfare impacts of all the targeting strategies are compared in Figure 3.

We find that the actual allocation of aid did not significantly increase welfare relative to a random allocation. Surprisingly, even if the government had been able to perfectly target the households with the largest damages from the earthquake, this would not have resulted in an increase in welfare relative to the random allocation. These targeting approaches actually do worse than random at targeting the poorest households. They are slightly better than random at increasing housing reconstruction, however.

If the government could have targeted aid optimally, this would have increased welfare by 77% more than a random allocation. However, this is probably difficult to achieve in practice, since temporary distress can be difficult to observe. On the other hand, if the government distributed the aid universally, this would have increased welfare by 12% relative to the random allocation, without counting the savings in administrative costs, or the benefits of getting the aid out more quickly. Other strategies perform better, including targeting households based on their liquidity or the quality of their housing stock, but these may be more difficult than the universal allocation in practice.

Figure 3: The welfare effects of different targeting strategies

These results suggest that the extensive rounds of targeting and building verification carried out in the aftermath of the earthquake did not add much value. The government would have generated more welfare if they had spent the resources used during the targeting process on increasing the aid budget, and distributing it universally.

References

Gordon, M, Y Hashida, and E Fenichel (2024), "Targeting Disaster Aid: A Structural Evaluation of a Large Earthquake Reconstruction Program." Working Paper.

The Asia Foundation (2016), "Nepal Government Distribution of Earthquake Reconstruction Cash Grants for Private Houses." https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Nepal-Govt-Distribution-of-Earthquake-Reconstruction-Cash-Grants-for-Private-Houses_June2017.pdf