Income support for laid-off formal workers can be beneficial even in countries with high informality, but how the benefits are disbursed matters

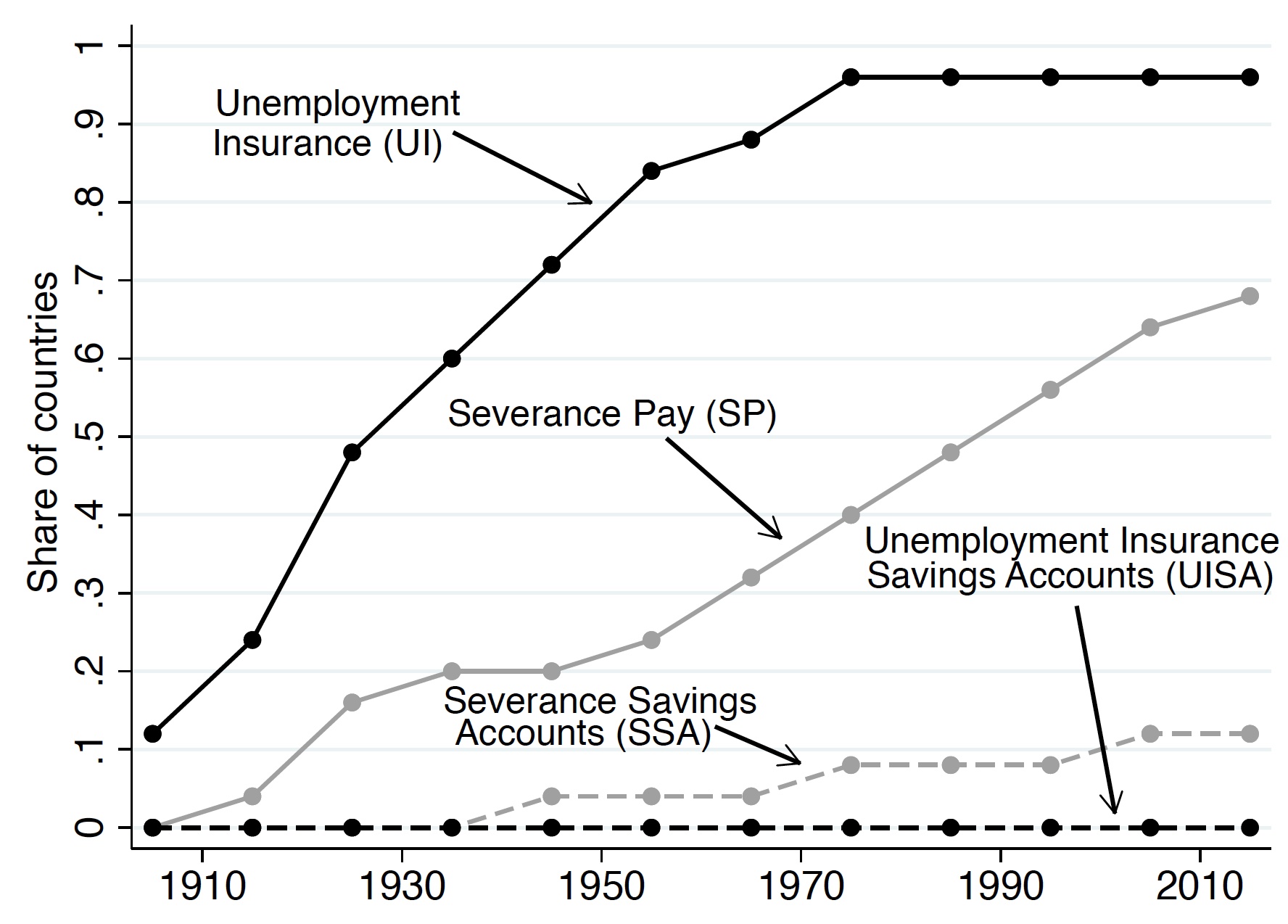

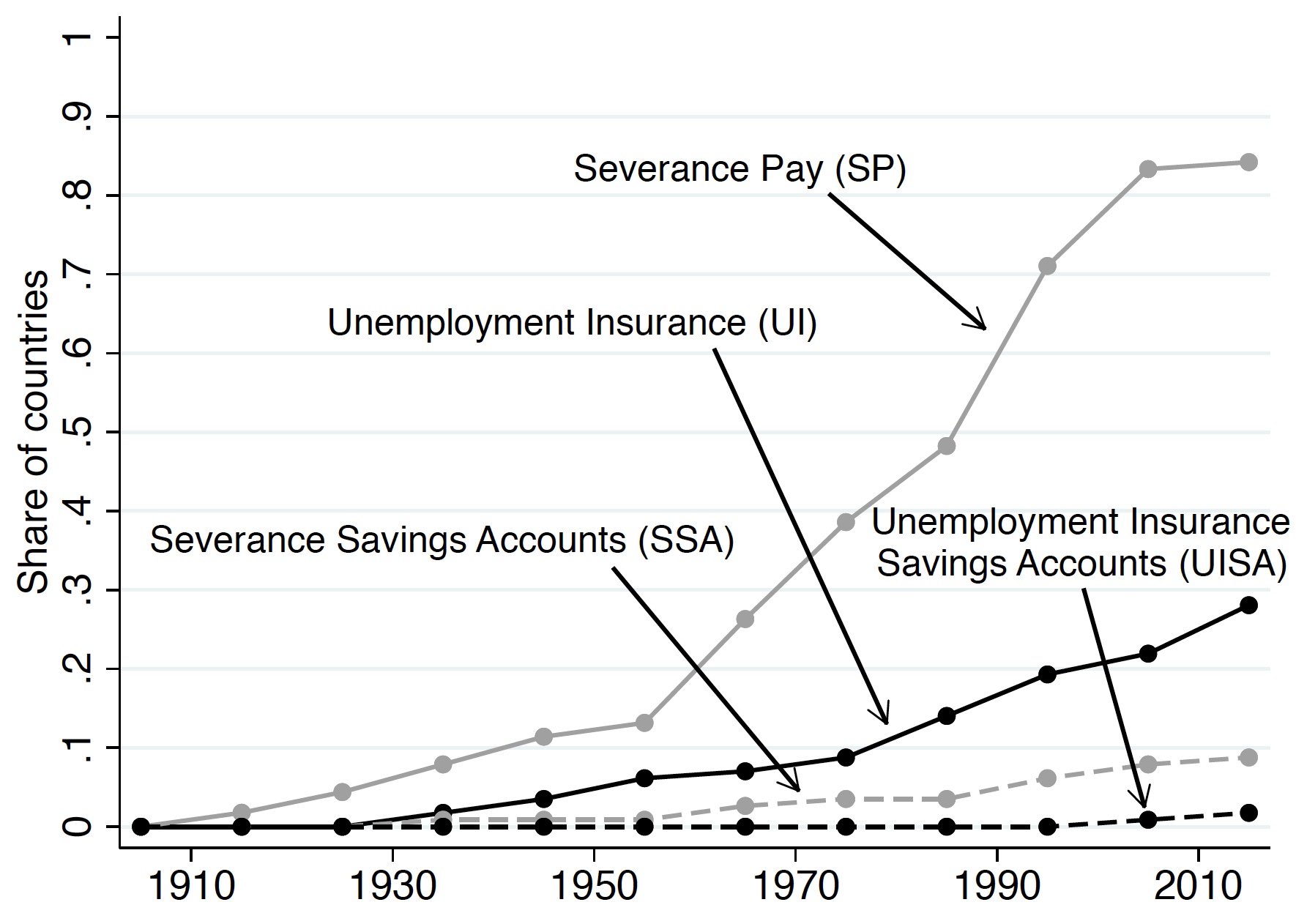

Job displacement insurance programmes that provide income support to laid-off workers, provided or mandated by the government, are becoming increasingly prevalent across the developing world. Figure 1 shows that the share of countries with unemployment insurance (UI) programmes – in which workers receive some amount periodically (such as monthly) as long as they remain without a job – has remained stable since the 1970s at about 95% in richer countries (Western Europe, US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand). By contrast, it has tripled over the same period in the rest of the world, from about 10% to about 30%. Moreover, while the share of countries with government-mandated severance pay (SP) programmes – in which workers receive some amount in a lump sum (i.e. one-off) after being laid-off – was about 40% in both groups of countries in the 1970s, it has increased to just under 70% in richer countries and more than 80% in the rest of the world.

The value of job displacement insurance programmes for laid-off workers in richer countries has been studied extensively (Chetty and Finkelstein 2013). In a recent paper (Gerard and Naritomi 2021), we shed new light on this question for the context of developing countries using data from Brazil.

Figure 1 Job displacement insurance (government-mandated) around the world

a) Western Europe, USA, CAN, AUS, NZ

b) Africa, Asia, Rest of Americas

Notes: From Gerard and Naritomi (2021). The figure displays the share of countries with government-mandated job displacement insurance programmes by decade. Data was collected for 139 countries in Western Europe, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand (panel a; 25 countries), and Africa, Asia, rest of the Americas (panel b; 114 countries). The programmes are categorised following Parsons (2016) based on their benefit payout schemes – lump-sum vs. state-contingent – and financing schemes – insurance-based vs. savings-based, such that separate graphs are displayed for Unemployment Insurance (UI; state-contingent, insurance), Severance Pay (SP; lump-sum, insurance), Unemployment Insurance Savings Account (UISA; state-contingent, forced savings), Severance Savings Account (SSA; lump-sum, forced savings).

The value of job displacement insurance programmes across contexts

Conceptually, the value of job displacement insurance programmes, as usually discussed in the context of richer countries, comes from the welfare gains from insuring workers against the risk of being laid-off and the risk of remaining without a job afterwards. For developing countries with large informal labour markets, there are three notable differences worth highlighting:

- First, job displacement insurance programmes can only provide insurance against the risk of being laid-off in the case of formal workers, meaning those whose job was registered and visible to the government. As a result, the coverage of such programmes is more limited in developing countries, where labour market informality is typically higher. Nevertheless, such programmes could still be very beneficial for the workers whom they can cover.

- Second, it is also the case that governments can only monitor reemployment for formal jobs (and not for informal jobs). As a result, the value of job displacement insurance programmes comes from the welfare gains from insuring formal workers against the risk of being laid-off and the risk of remaining without a formal job afterwards.

- Finally, as shown in Figure 1, SP programmes are relatively more common than UI programmes in developing countries that offer any job displacement insurance. This is likely due, in part, to the fact that SP programmes require less state capacity, as they most often mandate firms to make the lump-sum transfers to workers. However, little is known about the insurance value of these policies to workers in developed or developing countries.

Assessing the value of job displacement insurance programmes in practice

In general, it is quite challenging to assess the value of job displacement insurance programmes to workers. An influential approach in the literature consists of studying workers' consumption profile after a layoff, and the extent to which different policies help workers smooth their consumption while remaining without a (formal) job (Gruber 1997). Until recently, it was difficult to come across large longitudinal datasets on both consumption and employement to implement this approach. However, in the past few years, several research papers using new data sources have been able to implement this approach in richer countries (see Kolrsud et al. 2018 for Sweden, and Ganong and Noel 2019 for the US). The evidence indicates that there is a sizable need for insurance in these countries given the observed drop in workers’ consumption after a layoff and after workers stop receiving UI benefits.

It is not clear, however, that the available estimates are informative for developing countries, as the need for job displacement insurance may be different. On the one hand, it may be higher in developing countries if some of the usual means of self-insurance against income shocks in richer countries (for example, relying on formal credit) are more limited, as argued by Chetty and Looney (2007). On the other hand, it may be lower if formal employment is not workers’ usual employment status or if informal jobs are relatively easy to find after a layoff and pay similar wages as formal jobs.

Empirical evidence from Brazil

In our paper (Gerard and Naritomi 2021), we provide evidence on the value of job displacement insurance programmes in Brazil. Specifically, we implement a similar approach to previous research by exploiting a rare combination of high-frequency expenditure data and matched employee-employer data for more than 400,000 formal workers over five years in the state of São Paulo.1 Moreover, as displaced formal workers are eligible for both UI and SP in Brazil, we are able to compare the insurance value of SP and UI in the same context, which had not previously been studied, even for richer countries.

This is important because SP programmes are more prevalent in developing countries (see Figure 1) and the value of SP and UI may differ given their different disbursement policies. In particular, while UI benefits are disbursed periodically, the value of SP critically relies on workers' ability to utilise their lump sum progressively to smooth consumption after a layoff. However, there is evidence from other policy settings that consumption can be highly sensitive to cash-on-hand (for example, see Shapiro 2005 for food-stamps in the US).

Findings on (the lack of) consumption-smoothing

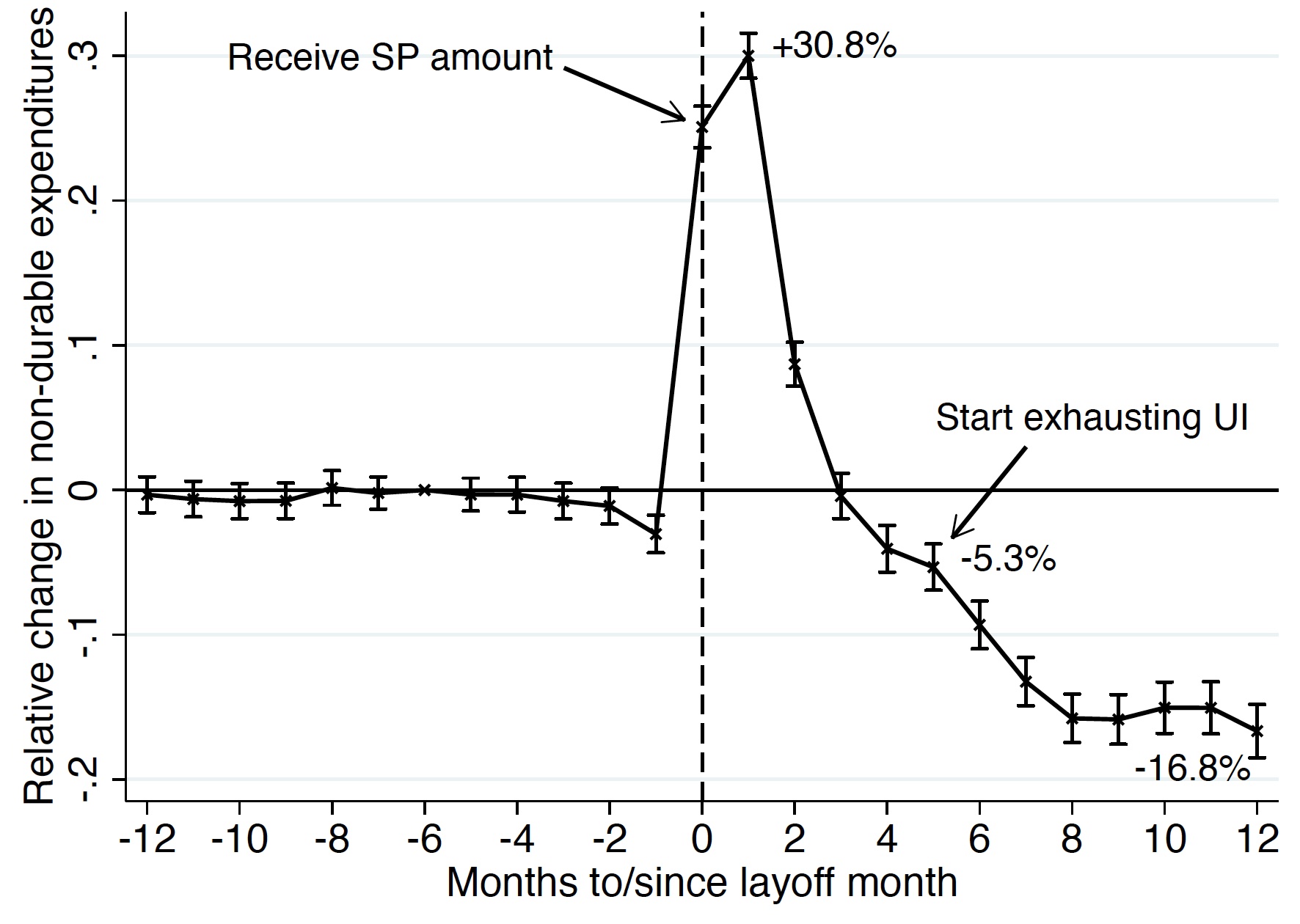

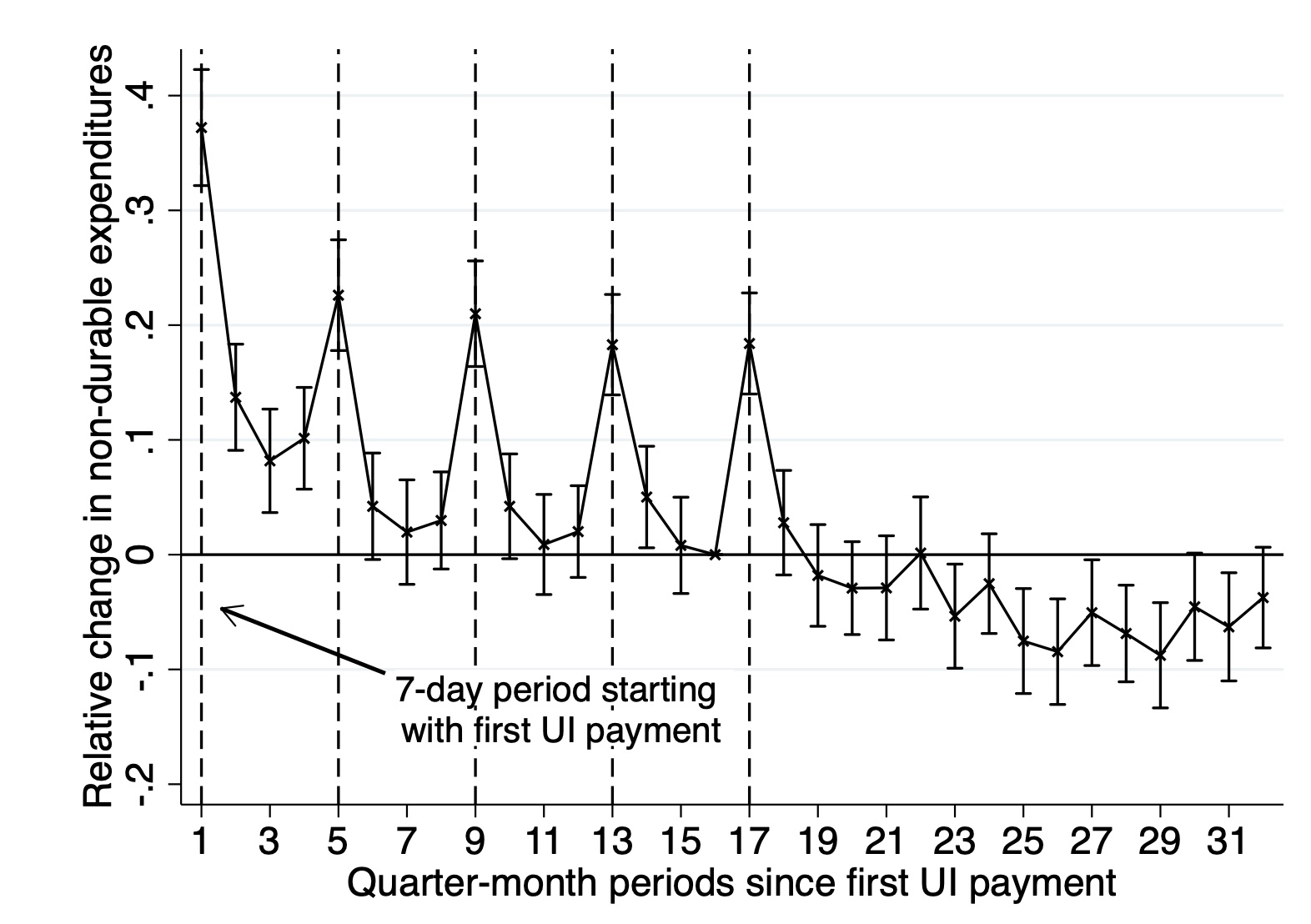

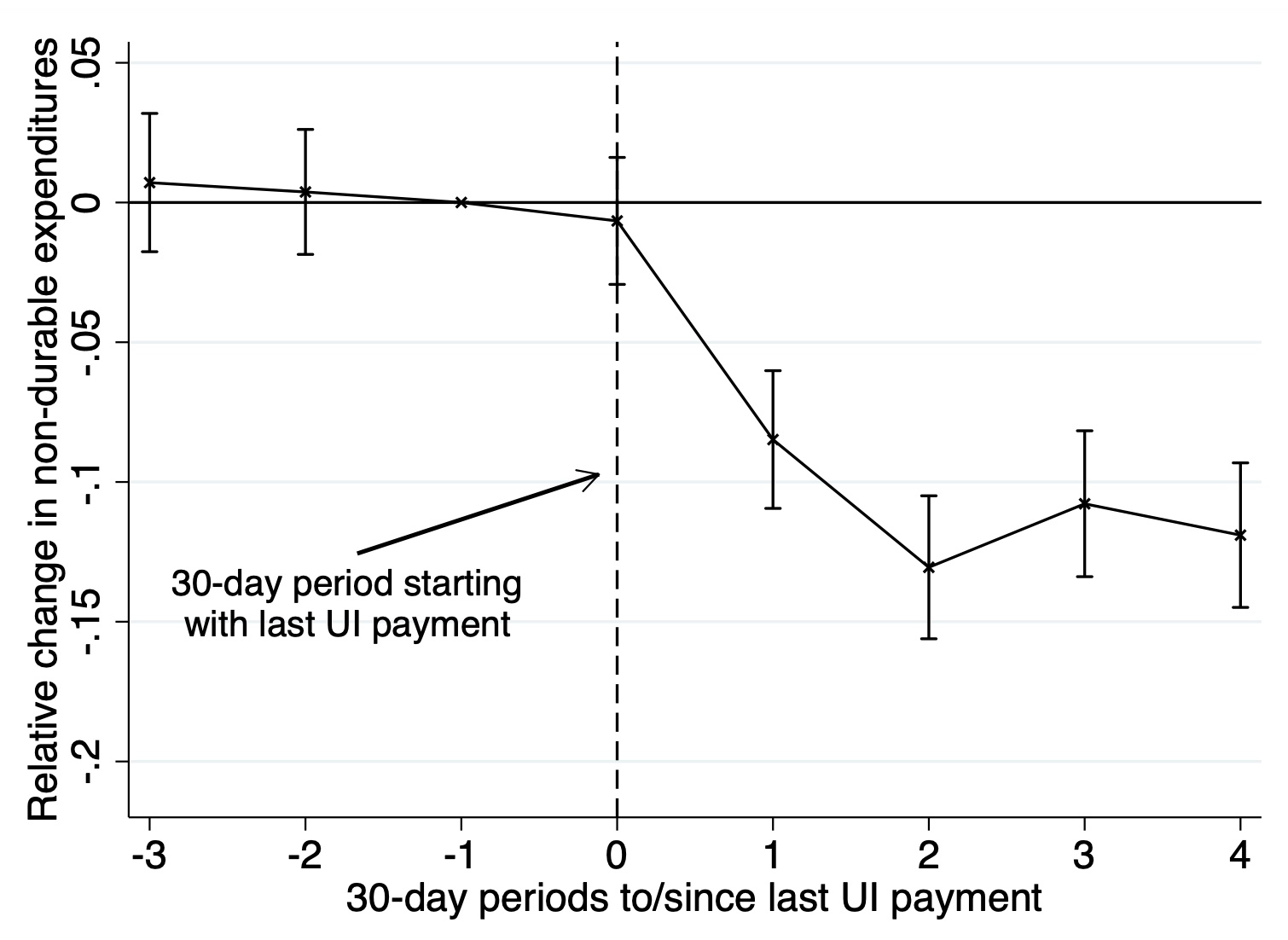

We find that workers increase non-durable consumption by more than 30% at layoff when they receive their SP, despite experiencing a long-term consumption loss of 17% when they stop receiving their UI benefits (Figure 2). Using administrative data on UI payments, we also find that workers spend 20% more in the week they receive their monthly UI paycheck (Figure 3). In addition, they fail to smooth consumption in anticipation of the (expected) drop in income when workers exhaust UI benefits, which is associated with a 10–15% drop in consumption (Figure 4). This sensitivity of consumer spending to cash-on-hand is present across spending categories, including sub-categories of non-durables such as food expenditures.

Figure 2 Consumer spending profile around layoff

Notes: From Gerard and Naritomi (2021). The figure presents difference-in-differences estimates (point estimates and 95% confidence intervals) of relative changes in non-durable expenditures around layoff (the vertical line indicates the layoff month) for workers who remain without a formal job. The sample is restricted to workers with at least 12 months of tenure. The pattern around UI exhaustion is fuzzy because workers exhaust UI benefits between months 5 and 7 after layoff. It is sharper in Figure 4, which presents the results of an analysis centred around UI exhaustion (rather than around layoff).

Figure 3 Consumer spending profile around UI payment dates

Notes: From Gerard and Naritomi (2021). The figure shows how non-durable expenditures change around UI payment dates within a month by presenting the results (point estimates and 95% confidence intervals) of an event analysis centered around UI payment dates. It uses the subset of layoff events for which workers were eligible for 5 months of UI and were observed drawing 5 monthly UI payments. The window of analysis starts at the first UI payment date. The time between two payment dates is divided into four ‘quarter-month’ periods (the first period includes the payment date). To investigate how expenditure levels evolve after UI exhaustion in the same analysis, comparable time periods were constructed for the period following the last UI payment. The sharp increases in the week of UI benefit receipt are similar if we restrict attention to workers who remain without a formal job until the end of the analysis window.

Figure 4 Consumer spending profile around UI exhaustion

Notes: From Gerard and Naritomi (2021). The figure presents the results (point estimates and 95% confidence intervals) of an event analysis centered around the date of the last UI payment (i.e. UI exhaustion) for relative changes in non-durable expenditures. As in Figure 3, it uses the subset of layoff events for which workers were eligible for 5 months of UI and were observed drawing 5 monthly UI payments. The figure aggregates the data by 30-day periods centered around UI exhaustion (the vertical line indicates the 30-day period starting with the last UI payment date). The drop at UI exhaustion is even larger (above 15%) if we restrict attention to workers who remain without a formal job until the end of the analysis window.

Our results show that the need for job displacement insurance can be sizable even in a developing country context with high labour market informality. We estimate a long-term loss in consumption once workers exhaust all their job displacement insurance benefits that is comparable to estimates from richer countries (see references above), despite the higher labour market informality in our setting. Informal sector employment thus serves, at best, as an imperfect form of self-insurance, and social insurance could lead to large welfare gains for displaced formal workers.

Our results also show that consumption is highly sensitive to cash-on-hand, even in the context of a relevant and salient negative shock, such as the loss of a formal job. We show that this evidence is consistent with workers being ‘present-biased’, leading them to over-spend a windfall of cash and under-save for an expected drop in income. In fact, in a survey with UI applicants in São Paulo, we find that a majority of respondents would not prefer to receive all their UI benefits as a lump-sum payment upon layoff, despite the clear financial advantages. Moreover, most of them mention the need to “control expenditures” or “not spend it all at once” as justification.

Policy implications

These consumer-spending patterns are particularly relevant for developing countries, as SP programmes are more prevalent in these countries. This could be partly explained by the fact that SP programmes are easier to administer relative to UI programmes, which require making payments periodically and monitoring workers’ reemployment, and that administrative contraints are likely more relevant for developing countries. However, by helping workers better smooth consumption, the trenched disbursement of UI benefits may be critical to the value of job displacement insurance programmes for workers.2 Moreover, the associated welfare gains for UI programmes compared to SP programmes could partially mitigate concerns related to the higher moral hazard problem with UI programmes.3 However, implementing UI programmes may require sizable investments in state capacity in some countries.

References

Chetty, R and A Finkelstein (2013), “Social insurance: Connecting theory to data", Handbook of Public Economics 5: 111-193.

Chetty, R and A Looney (2007), “Income risk and the benefits of social insurance: Evidence from Indonesia and the United States”, Fiscal Policy and Management in East Asia, NBER East Asia Seminar on Economics 16 (eds. T Ito and A Rose): Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Ganong, P and P Noel (2019), “Consumer spending during unemployment: Positive and normative implications”, American Economic Review 109(7): 2383-2424.

Gerard, F and J Naritomi (2021), “Job displacement insurance and (the lack of) consumption smoothing”, American Economic Review (forthcoming).

Gruber, J (1997), “The consumption smoothing benefits of unemployment insurance”, American Economic Review 87(1): 192-205.

Kolsrud, J, C Landais, P Nilsson and J Spinnewijn (2018), “The optimal timing of unemployment benefits: Theory and evidence from Sweden”, American Economic Review 108 (4-5): 985-1033.

Parsons, D (2016), “Job displacement insurance: A policy typology”, IZA Working Paper, 9865.

Shapiro, J M (2005), “Is there a daily discount rate? Evidence from the food stamp nutrition cycle”, Journal of Public Economics 89(2-3): 303-325.

Endnotes

1 We use a combination of de-identified expenditure data from VAT receipts originally linked to individual identifiers and matched employee-employer data in the state of São Paulo, Brazil. This dataset allows us to track formal employment history and a wide range of spending categories across time based on a 7-digit sector classification of shops that issue receipts to consumers.

2 Our results do not imply that the lump-sum disbursement of benefits should be avoided in general. The same reasons that may prevent workers from dissaving their SP amount more slowly may justify the existence of forced savings to mobilise the resources necessary for lumpy investments that workers may not be able to make otherwise. The key implication of our findings is that, if the goal of a policy is to provide insurance to displaced workers, a lump-sum disbursement could undermine this goal. Workers may still benefit from forced savings and occasional access to these resources in a lump-sum fashion for other purposes or at other times.

3 The moral hazard problem with UI programmes is the welfare loss from distorting incentives to find a new job.