Insights from high-frequency phone survey data collection reveal that access, rather than hesitancy, prevents vaccine uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa

COVID-19 vaccination rates in Sub-Saharan Africa remain low as a lack of easy access to vaccines keeps high vaccine acceptance from translating to widespread coverage.

March 11, 2023, marked the three-year anniversary of COVID-19 being assigned pandemic status by the World Health Organization. Exactly 8 months later, on December 11, 2020, the first COVID-19 vaccine received emergency approval by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration. This was the start of an unprecedented global vaccination effort under which, to date, more than 5.5 billion people, 70% of the world population, have received the COVID-19 jab (Mathieu et al. 2021).

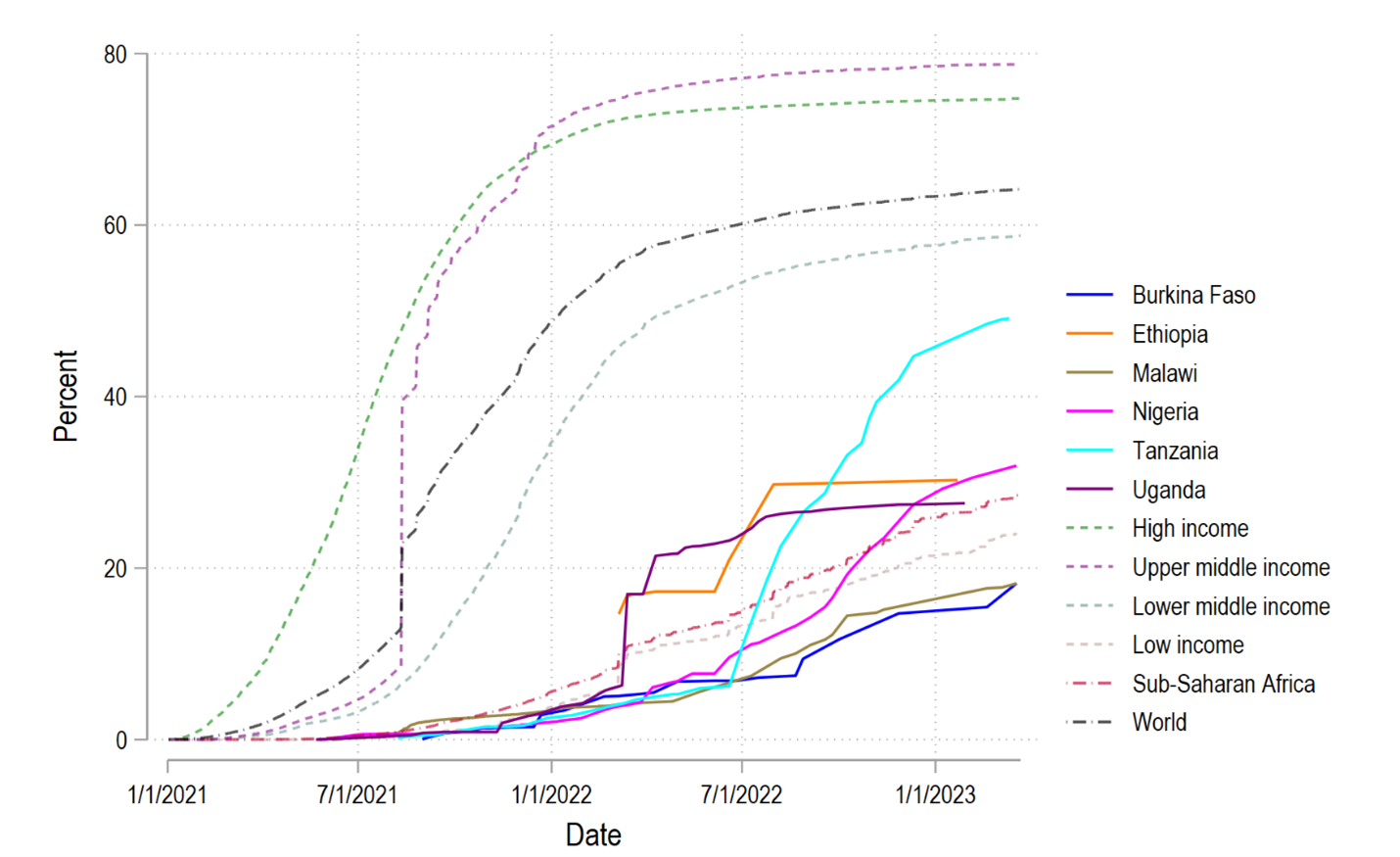

Notwithstanding the impressive scale of this achievement, the distribution and coverage of COVID-19 vaccines has been highly unequal. In particular, COVID-19 vaccination rates in Sub-Saharan Africa have trailed the rest of the world. As of March 24 2023, fewer than three in ten people in Sub-Saharan Africa have been fully vaccinated (Figure 1).

Low vaccine uptake contrasts with evidence of a consistent high willingness to be vaccinated in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. This raises the question: why has vaccine uptake remained so low? In this blog post, we revisit over two years’ worth of research and analysis on COVID-19 vaccination attitudes and uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa published in Kanyanda et al. (2021), Wollburg et al. (2022) and Wollburg et al. (2023).

These studies use over 40,000 data points across 21 survey rounds with information on vaccine attitudes from October 2020 to October 2022. They draw on data from national high-frequency phone surveys in six countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania; see World Bank 2023). These were enabled by the existing infrastructure of the Living Standard Measurement Study – Integrated Survey on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) panels in these countries (Gourlay et al. 2021).

Figure 1. COVID-19 vaccination rates in selected countries and regions

Notes: Share of people fully vaccinated. Source: Mathieu et al. (2021)

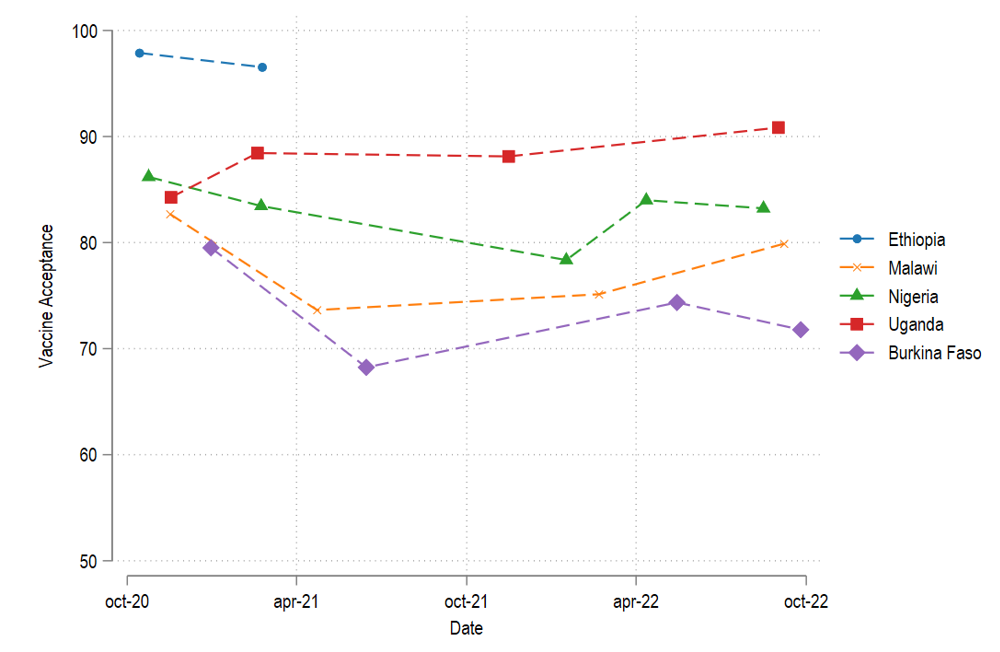

Vaccine attitudes change but overall acceptance remained high throughout the pandemic

We find high levels of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance throughout 2020, 2021, and 2022 (Figure 2). In any given year covered by our data collection, more than 8 in 10 people were willing to get vaccinated. However, vaccine acceptance was highest before the availability of vaccines and about 5 percentage points lower in 2022 than in 2020. Vaccine acceptance across our study countries was 88.8% in 2020, 85.2% in 2021, and 83.6% in 2022. Over time, 27.4% of respondents changed their vaccine attitudes at least once, and 13.9% twice or more.

Figure 2. Vaccine acceptance over time

Vaccine hesitancy differs between population groups and is driven by safety and side-effect concerns

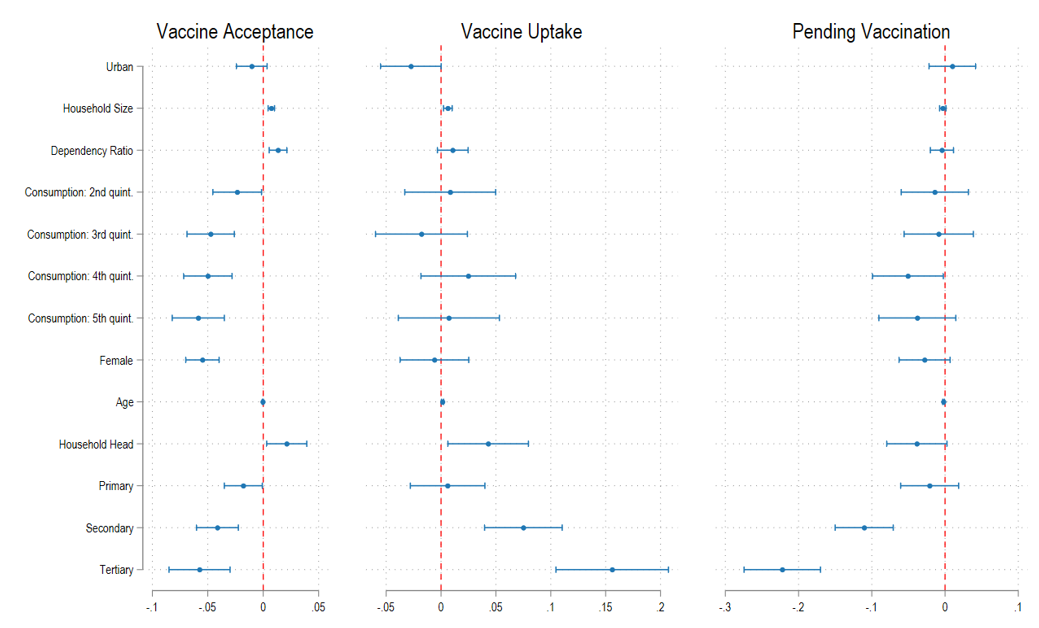

Vaccine hesitancy varies across population groups. We use a set of multivariate logit regressions to explore the correlates of vaccine hesitancy (Figure 3). We find that vaccine hesitancy is more common among better-off households and individuals with higher levels of education. In contrast, household size and household dependency ratio (typically associated with lower income) are correlated with vaccine acceptance. Finally, women are around five percent less likely willing to be vaccinated than men. These patterns suggest that better-off and better-educated individuals and households - arguably those with easier access to vaccines - tend to be more vaccine hesitant than worse-off households.

We contrast the correlates of vaccine hesitancy with the correlates of vaccine uptake. This comparison gives us a sense of whether those who are willing to be vaccinated end up getting vaccinated. Two findings stand out. First, the income gradient in vaccine hesitancy does not translate to vaccine uptake. Second, the negative relationship between educational attainment and vaccine acceptance is reversed for vaccine uptake, that is, better educated individuals are more likely to be vaccinated. As a result, educational attainment is lower among those who are willing but as-yet unvaccinated. These results suggest that willingness to be vaccinated does not always translate to vaccine uptake. One plausible explanation is that wealth and socio-economic status are associated with easier access to vaccinations, which compensates for the lower willingness to get vaccinated among the better-off households.

Figure 3: Correlates of vaccine acceptance, uptake, and pending vaccination (despite willingness to get vaccinated).

Note: Marginal effects from multivariate logit regressions. All models also include country fixed effects which are not plotted. Models on vaccine uptake and pending vaccination also contain year fixed effects. Those coded as pending vaccination are those who are willing but yet unvaccinated. The based category for this group are those who are already vaccinated. Bars are 95% confidence intervals.

What are respondents’ stated reasons for vaccine hesitancy and motivations to get vaccinated? In our sample, concerns about side effects (29.8%), concerns for vaccine safety (19.9%), and thinking that one is not at risk enough to warrant vaccination (15.1%) are the most frequent reasons for vaccine hesitancy. Conversely, many of those who are already vaccinated report that protecting their own health was the primary or only reason to get vaccinated (Malawi: 89.9%; Uganda: 65.1%; Nigeria: 64.1%; Burkina Faso: 60.8%).

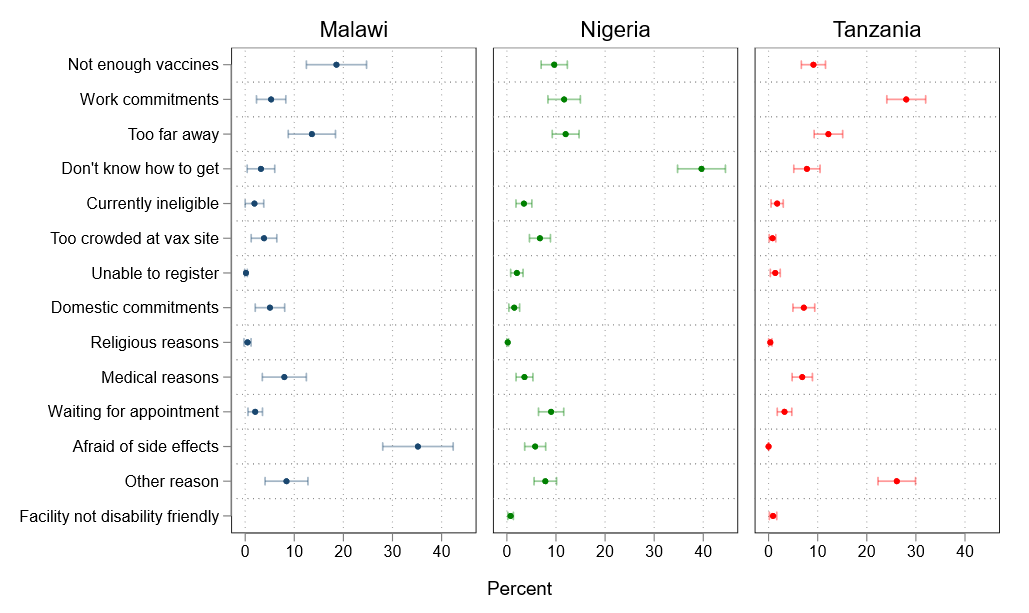

Opportunity costs and barriers to access COVID-19 vaccines prevent uptake

What is preventing those who are willing to be vaccinated from doing so? We asked respondents in three countries (Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania) why they have not received the vaccine even though they declared to be willing to do so. Reasons differed but suggested that accessibility as well as the opportunity costs of getting vaccinated matter (Figure 4).

A sizeable share of respondents reported prohibitively long distances to the nearest vaccination point in all three countries (Malawi: 13.6%, Nigeria: 12%, Tanzania: 12.2%). In Tanzania and Nigeria, traveling to the vaccination site also often clashed with work commitments (11.7% and 28%, respectively), especially in urban areas. In Nigeria, 40% of unvaccinated respondents reported that they did not know how to get vaccinated. We also found evidence of perceived supply side barriers, especially in Malawi, where 18.6% of respondents stated there weren’t enough vaccines.

Figure 4: Reasons for pending vaccination despite being willing to get vaccinated.

Notes: Reasons for pending vaccination despite willingness to get vaccinated. The dots represent estimate means, the bards around the 95% confidence interval of the estimate. Malawi (n=493), Nigeria (n=1098), Tanzania (n=992).

Trusted information sources and mass media can mobilize the unvaccinated

As many in Sub-Saharan Africa remains unvaccinated, outreach efforts to promote vaccine uptake will have to continue for the foreseeable future. Such efforts could leverage radio broadcasts which are the most trusted information channel on COVID-19 for more than half of respondents in every country we study. Additionally, the source of trusted COVID-19 vaccine information appears to matter with medical professionals topping the list in three out of four countries.

Almost six in ten respondents who are hesitant to get vaccinated say they could be convinced by someone else to change their stance. Most commonly, respondents say their opinion may be swayed by the recommendation of medical professionals or that of family or community members. We also find overwhelming willingness to recommend the COVID-19 vaccine: Over nine in ten vaccinated respondents across our study countries say they would be ‘very likely’ or ‘somewhat likely’ to encourage others to get vaccinated.

Closing the COVID-19 vaccination gap in Sub-Saharan Africa

COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in Sub-Saharan Africa continue to trail the rest of the world. More than two years of research on COVID-19 vaccination attitudes suggest, however, that vaccine acceptance in the region is generally high. Our research, and that of others in the field, points to barriers in the ease of access and last-mile delivery of vaccinations as constraints that hamper the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines (Reza et al. 2022, Mobarak et al. 2022). This underscores that willingness to be vaccinated need not translate into getting vaccinated if the vaccination process is cumbersome and getting vaccinated is not an immediate priority.

To increase uptake, access needs to be made easier. Vaccine hesitant individuals may be convinced through reinforced communications and vaccine ambassadors such as doctors or family members. The fact that health considerations are, at the same time, the primary reason for hesitancy and uptake of the vaccine suggests that emphasizing the relative safety and health benefits of COVID-19 vaccination is key for such messaging.

References

Gourlay, S, T Kilic, A Martuscelli, P Wollburg, and A Zezza (2021), “Viewpoint: High-Frequency Phone Surveys on COVID-19: Good Practices, Open Questions.” Food Policy 105: 102153.

Kanyanda, S, Y Markhof, P Wollburg, and A Zezza (2021), “Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Six National Phone Surveys.” BMJ Open 11(12): e055159.

Mathieu, E, H Ritchie, E Ortiz-Ospina, M Roser, J Hasell, C Appel, C Giattino, and L Rodés-Guirao. 2021. “A Global Database of COVID-19 Vaccinations.” Nature Human Behaviour 5(7): 947–53.

Mobarak, A M, E Miguel, J Abaluck, A Ahuja, M Alsan, A Banerjee, E Breza, et al. 2022. “End COVID-19 in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” Science 375 (6585): 1105–10.

Reza, H M, V Agarwal, F Sultana, R Bari, and A M Mobarak (2022), “Why Are Vaccination Rates Lower in Low and Middle Income Countries, and What Can We Do about It?” BMJ: e069506.

Wollburg, P, Y Markhof, S Kanyanda, and A Zezza (2022), “Turning COVID-19 Vaccines into Vaccinations: New Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Policy Research Working Paper Series 10152. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Wollburg, P, Y Markhof, S Kanyanda, and A Zezza (2023), “The Evolution of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Sub-Saharan Africa : Evidence from Panel Survey Data.” 10275. Policy Research Working Paper. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank (2023), “LSMS High-Frequency Phone Surveys.” Available here.