Improving consumer information can increase the productivity of smallholder farmers by helping them detect product quality

In a poor information environment where buyers cannot perfectly observe product quality, a market breakdown can occur in which selling high quality products may not be profitable (Akerlof 1970). While there are common policies that can counteract these tendencies (Dranove and Jin 2010), the mechanisms they depend on may not always function well, particularly in the context of lower-income countries. For example, lower access to information technology or lower levels of education may slow the diffusion of consumer information. Lower state capacity can mean that quality standards, licensing requirements, disclosure rules, or other regulations may be difficult to enforce, thereby undermining the ability of these policies to address the market failure.

Learning from hybrid maize seed markets in Kenya

We used a field experiment to study the market-level effects of improving consumer information, using the hybrid maize seed market in rural Kenya as a case study (Hsu and Wambugu 2023). In this setting, it is difficult for consumers to directly observe seed quality as lower and higher quality seeds visually look similar (Gharib et al 2021), while the performance of maize seeds depends on numerous factors. As a result, yields tend to be noisy, imperfect signals of seed quality (Bold et al. 2017, de Brauw and Kramer 2022). The frequency of observing these signals is limited by the crop cycle, and therefore farmers typically only purchase seeds once or twice per year. Branding and reputation building may be undermined by the presence of counterfeit or expired seeds.

All of these channels can work to hinder consumer learning and while regulations exist to establish minimum quality standards for seeds, enforcement is limited.

It is in this setting that we study the effects of a program to enhance farmers’ ability to distinguish between higher and lower quality hybrid seeds (Hsu and Wambugu 2023). We implement a market-level field experiment across 386 rural market areas in four counties in western Kenya. From this sample, markets were randomly selected to receive community wide trainings that enabled farmers to better detect quality-verified maize seeds. On average, they consisted of two days of activities with research staff having both group conversations and one-on-one conversations about observable markers on seed packets. These markers are often related to existing quality certification procedures and are correlated with higher seed quality. Using a series of surveys and secret shopper activities, we track outcomes in the market for both treatment and controls sites, including household knowledge, seed purchases, and agricultural outcomes as well as the number of sellers in a market. The sample of sites includes 104 pure control sites in which no baseline activities were conducted. This makes it possible to test whether baseline activities may have inadvertently influenced outcomes. A follow-up period of just over one year allows us to track possible convergence over time to a new equilibrium over the course of three planting seasons.

The information treatment provided a way to obtain higher quality seeds

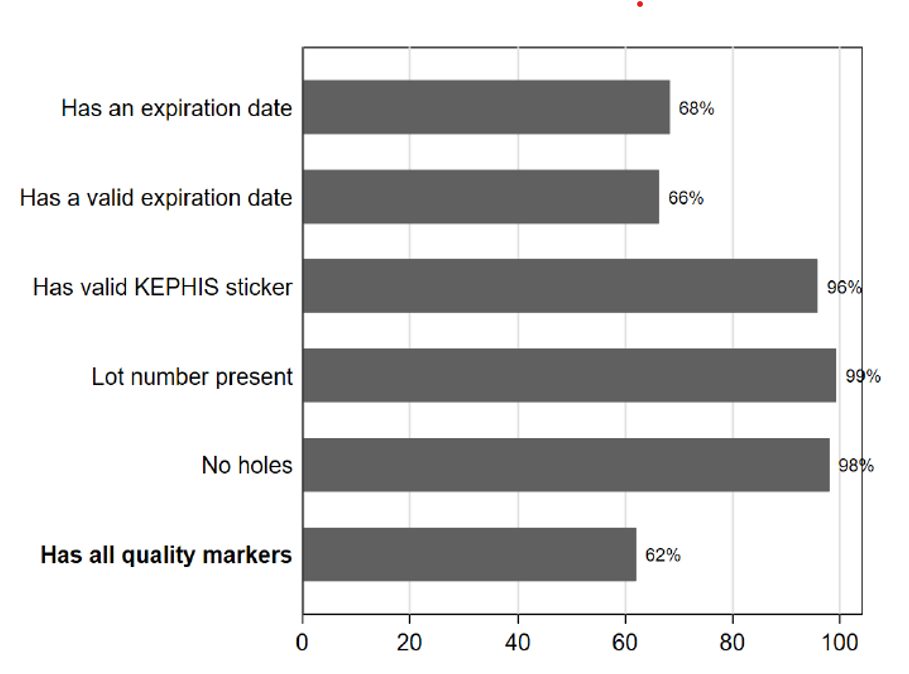

Secret shoppers obtained seed samples from sellers at the study sites during the planting seasons following treatment. Samples were tested for purity and germination rate. Overall, 42% of packets in control markets are missing one or more quality markers as illustrated in Figure 1. Seed packets that were missing quality markers had about a 5% lower germination rate when compared to packets that had all quality markers. Seeds can perform poorly even if they germinate well, and germination rate is not the only measure of seed quality. Nevertheless, the fact that quality-verified packets have higher germination rates indicates that the consumer information intervention can directly lead to higher maize productivity if farmers apply the information to their purchasing decisions.

Figure 1

Note: the sample includes 1508 seed packets that were observed in one of the three planting seasons following treatment.

Informed farmers changed where they bought seeds and achieved higher agricultural productivity

The analysis shows that the information treatment successfully increased recall of knowledge about the quality markers, and treated farmers were more likely to report using the detection techniques. Treatment caused some farmers to change where they purchased seeds with farmers being about 16% less likely to buy hybrid seeds from their local market, with a similar increase in farmers buying seeds from a different source. After harvest, treated farmers saw about 5% higher maize yield. This pattern of results is consistent with improved consumer information causing changes in buying behavior and causing informed farmers to obtain higher quality seeds.

Treatment caused some shops to stop selling maize

Among the remaining shops, secret shoppers mimicking uninformed buyers saw no detectable change in seed quality. In subsequent planting seasons, treatment caused a 17% net decrease in the number of sellers offering maize. Meanwhile, secret shoppers that behaved as if they were uninformed buyers paid visits to randomly selected shops that remained as maize seed sellers. Labs tests show no detectable change in seed quality, nor was there a detectable change in the frequency of having all quality markers.

Conclusion

Our paper offers experimental evidence on an important policy issue—boosting agricultural productivity by addressing the use of low-quality agricultural inputs. The findings suggest that policies that improve consumer information can increase the productivity of small-holder farmers. One way to view the results is to ask whether community trainings that help consumers detect product quality should be scaled up. In the paper’s setting, the market value of the estimated 50 to 60 kgs gain in maize harvested far exceeds the estimated US$2 to US$4 cost per household of disseminating the information. Of course, such a cost-benefit calculation does not include costs borne by the regulators in establishing the quality verification system, and likely also reflects the absence of any previous major public information campaign on the subject. Existing language on seed packages could also better communicate how quality markers can be used. Additionally, in our view it is likely that alternative communication strategies—for example using mass media such as radio and newspapers—could promote the usage of observable quality marks more efficiently than in-person training.

From an academic point of view, the paper extends our understanding of how markets in low-information environments operate in the real world. While the paper focuses on the hybrid maize seed market in Kenya, the regulatory challenges in this market are likely to be relevant in many other markets where consumers have difficulties knowing the quality of a good or service (Kenya Association of Manufacturers 2012). For example, similar information frictions have been documented in markets for other agricultural inputs (e.g. Michelson et al. 2021; Ashour et al 2019) and for health products (e.g. Bjorkman-Nyqvist et al. 2021).

An important finding from our paper is that improved consumer information did not lead uninformed buyers to have better access to high quality seeds. Instead of upgrading quality, sellers responded by quitting the market for hybrid maize seed. Why is that? The relative cost to sellers of upgrading stock from low to high quality may be important for determining if sellers can be induced by improved consumer information to upgrade quality. Future work can usefully explore other policies that affect the seller’s choice of quality, the role of consumer information at scale, and how consumer information interacts with other common regulatory tools, such as monitoring and enforcement activities.

References

Akerlof, G A (1970), “The Market for ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 84(3): 488-500.

Ashour, Maha, D O Gilligan, J B Hoel, and N I Karachiwalla (2019), “Do Beliefs About Herbicide Quality Correspond with Actual Quality in Local Markets? Evidence from Uganda”, Journal of Development Studies 55(6): 1285-1306.

Bjorkman-Nyqvist, M, J Svensson, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2021), “Can Good Products Drive Out Bad? A Randomized Intervention in the Antimalarial Medicine Market in Uganda” Journal of the European Economic Association 20(3): 957-1000.

Bold, T, K C Kaizzi, J Svensson, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2017), “Lemon Technologies and Adoption: Measurement, Theory and Evidence from Agricultural Markets in Uganda”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(3): 1055-1100 .

de Brauw, A and B Kramer (2022), "Improving trust and reciprocity in agricultural input markets: A lab-in-the-field experiment in Bangladesh", International Food Policy Research Institute.

Dranove, D and G Zhe Jin (2010), “Quality Disclosure and Certification: Theory and Practice”, Journal of Economic Literature, 2010.

Gharib, M H, L H Palm-Forster, T J Lybbert, and K D Messer (2021), “Fear of fraud and willingness to pay for hybrid maize seed in Kenya”, Food Policy, 102: 102040.

Hsu, E and A Wambugu (2023), “Can informed buyers improve goods quality? Experimental evidence from crop seeds”, Working Paper.

Kenya Association of Manufacturers (2012), “The Study to determine the severity of the counterfeit problem in Kenya”.

Michelson, H, A Fairbairn, B Ellison, A Maertens, and V Manyong (2021), “Misperceived quality: Fertilizer in Tanzania”, Journal of Development Economics, 148: 102579.