Evidence from Tanzania shows fertiliser quality is not the problem, rather it is farmers’ perceived belief of bad fertiliser quality that is

In most of sub-Saharan Africa, limited fertiliser use on small farms is a dominant factor contributing to poor crop yields, low incomes, and food insecurity (Sheahan and Barrett 2017, Sanchez 2002). Numerous factors contribute to persistently low fertiliser usage including high fertiliser prices and variable crop prices, farmer risk-aversion, and limited access to credit and insurance (Feder et al. 1985, Foster and Rosenzweig 2010, Duflo et al. 2011, Karlan et al. 2013). However, amidst this debate as to the key factors, the perceived quality of the fertiliser itself is often missed.

We show that the perceived quality of the fertiliser itself isanother important factor at play in farmer’s decision not to use fertiliser. Farmers in these regions have voiced suspicion that the product available to them in local markets has been adulterated. Farmers suspect that fertiliser has been mixed with salt, sand, or concrete to increase dealer profits at the expense of the farmer. As a result, fertiliser usage might be low because the farmers may not be willing to buy fertiliser that they believe is adulterated.

In our study, we wanted to answer two questions:

- Is the fertiliser available to farmers actually adulterated or is the nutrient content as advertised by the dealer?

- Do farmers limit their usage of fertiliser because they think it is adulterated?

Fertiliser quality in Tanzania

In Michelson et al. (2018), we answered these questions in one region of Tanzania using laboratory tests of fertiliser samples, a survey, and an assessment farmer’s willingness-to-pay (WTP)

- We identified and surveyed all 225 fertiliser sellers in the Morogoro Region of Tanzania.

- We purchased multiple samples of fertiliser from these sellers using mystery-shoppers and tested the fertiliser nutrient content in Kenyan and US-based laboratories.

- We assessed farmers’ WTP for fertiliser that we purchased in local markets.

Fertiliser quality is good

We find that fertiliser largely meets nutrient standards. Though we sampled several varieties of fertiliser, we focus here on urea because it is the most widely used in this region, especially among small farmers. We found that only 2% of urea samples were out of compliance with international nutrient standards. On average, the tested urea contained 45.9% nitrogen compared to the advertised 46%, an insignificant difference.Our finding that fertiliser nutrient quality consistently meets advertised standards agrees with results from recent studies by the International Fertiliser Development Corporation (Sanabria et al. 2013) in several countries in West Africa, and by the International Food and Policy Research Institute in Uganda (Ashour et al. 2017). As yet, only one study has found highly variable nutrient content with average nitrogen deviations of 30% in urea in Uganda (Bold et al. 2018).

An insight acquired directly from the fertiliser industry is that profitable fertiliser adulteration is difficult. Substantial quantities of low-value fillers must be included for any impact on profit. Moreover, when adulteration reaches such levels, only farmers with minimal knowledge of fertilisers are likely to be deceived. Urea presents a special challenge because urea prills are small, white, opaque, and relatively uniform in size and colour, and very few plausible fillers cost less than the urea itself.

Farmers believe fertiliser is adulterated even when it is not

We surveyed 165 farmers in Morogoro Region, collecting information on fertiliser use and their perceptions regarding fertiliser quality. Among our sample, 36% reported concerns about adulterated fertiliser in markets, 18% of the sample believed that more than half of the fertiliser for sale was likely adulterated.

Why is there such widespread suspicion among small farmers about fertiliser quality? With poor access to accurate information, farmer concerns are reinforced by periodic stories in the popular press of fake-fertiliser seizures. In Tanzania, for example, The Citizen, a major English Language newspaper, reported in 2016 that the Tanzania Fertiliser Regulatory Authority had discovered “fake” fertiliser in markets across the country, and that 40% of fertiliser for sale in the country was counterfeit (Kasumuni 2016). In 2014 the same newspaper reported a seizure and destruction of counterfeit fertiliser (Lugongo 2014). Similar stories have run in countries including Uganda, Ghana, Nigeria, and Kenya. Farmers have taken such reports seriously: we find that they are willing to pay considerably less for fertilisers in the market than they are for researcher-certified fertilisers.

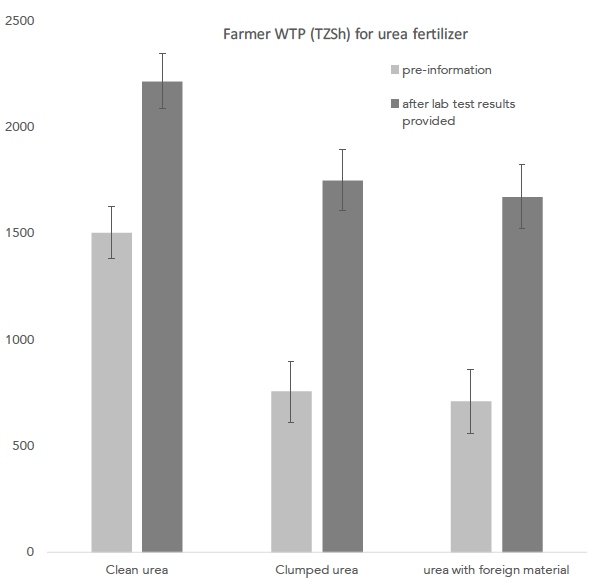

To assess local demand for fertiliser, we set up a willingness-to-pay exercise with farmers using three samples of urea fertiliser which we had purchased locally and lab-tested to ensure that each met required industry standards. For each urea sample, we asked the farmer to state their WTP, first without providing any additional information about the nutrient content, and then when informed that the fertiliser had been certified by a reputable laboratory as meeting industry standards. The first two columns of Figure 1 display the results from this exercise (the “clean urea” columns). We find that farmers are willing to pay considerably more for lab-certified fertilisers than for uncertified product. Their WTP for one kilo of urea fertiliser in the absence of information about its nutrient content proved to be 32% lower than the post-information WTP.

Beliefs about quality are driven by fertiliser’s physical appearance

We also find that farmers incorrectly believe the physical appearance of the fertiliser reflects its nutrient quality. More than 25% of fertiliser purchased in local markets exhibits caking, clumping, and powdering. These degradations in physical characteristics occur due to poor shipping, storage, and handling. Fertiliser that we purchased sometimes included big, hard aggregates larger than a golf ball or appeared wet or dirty. Even so, lab results from tests of these samples reveal that the nutrient content is as advertised. This being said, we find that WTP depends heavily on the physical characteristics of the samples. Two of the three samples we asked farmers to assess had poor physical characteristics: one included large clumped aggregates and the other appeared to contain a small amount of some foreign material mixed in with the urea. Prior to the provision of the lab tests information, farmers heavily discounted the poor looking samples (Figure 1). WTP increases significantly – exceeding the market price of 1,500 Tanzanian shillings – for all three samples after farmers were provided the lab results.

Figure 1 Effect of information about unobservable nitrogen content on farmer reported WTP for clean urea and urea with poor physical characteristics

Note: The prevailing market price for one kilo of urea at the time was 1,500 Tanzanian shillings

Why has there been no attention to this matter of physical appearance among fertiliser retailers, given its importance to farmers? We found an answer to this question by studying the fertiliser supply chain in Tanzania. Nearly all fertiliser for sale in Tanzania is imported. We visited ports, warehouses, and bagging facilities and found that problems related to fertiliser’s physical characteristics likely begin upstream in the supply chain, close to the port, and so nearly all dealers have some chance in any given shipment of having such issues. Indeed, 87% of the dealers had at least one fertiliser sample that contained clumps, and 33% had at least one discoloured sample.

Policy recommendations: We must think beyond input quality

Our results:

- The quality of fertilisers for sale in an important agricultural region of Tanzania largely meets national manufacturing standards for nutrient content.

- Belief of rampant product adulteration persists among farmers in these markets.

- Farmers make purchase decisions based on (incorrectly) inferring unobservable nutrient content from poor quality characteristics that they can observe.

These insights may apply to other agricultural inputs such as seed and herbicide as well as other countries in the region.1 Our results demonstrate the importance of thinking beyond problems of fertiliser adulteration in research and policy design focused on input quality. Adulteration may not be a widespread problem – the problem may be that farmers think that it is and that it is hard for them to learn about the true quality given the intrinsic inter-annual variability in agricultural production. It is critical to understand what farmers think about fertiliser quality and why if we hope to design policies to improve the situation.

Editor's note: This column is based on PEDL project.

References

Ashour, M, L Billings, D Gilligan, A Jilani and N Karachiwalla (2017), “Evaluation of the impact of e-verification counterfeit agricultural inputs and technology adoption in Uganda: Fertiliser testing report”, Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Bold, T, K Kaizzi, J Svensson and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2017), “Lemon technologies and adoption: Measurement, theory and evidence from agricultural markets in Uganda”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(3): 1055--1100.

Duflo, E, M Kremer and J Robinson (2011), “Nudging farmers to use fertiliser: Theory and experimental evidence from Kenya”, American Economic Review 101(6): 2350–2390.

Feder, G, R Just and D Zilberman (1985), “Adoption of agricultural innovations in developing countries: A survey”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 33(2): 255–298.

Foster, A and M Rosenzweig (2010), “Microeconomics of technology adoption”, Annual Review of Economics 2: 395–424.

Karlan, D, R Osei, I Osei-Akoto and C Udry (2014), “Agricultural decisions after relaxing credit and risk constraints”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2): 597–652.

Sanabria, J, G Dimithe, E Alognikou (2013), “The quality of fertiliser traded in West Africa: Evidence for stronger control”, IFDC Report.

Endnotes

[1] In some regions and for some products, agronomic quality of inputs is a problem; Ashour et al (2017) find problems with herbicide dilution in Uganda. Evidence is still accumulating on where and what the problems are for inputs content quality.