Enabling teachers to introduce pedagogical innovations can deliver substantial gains in student achievement. An experimental programme in Brazil unveils the importance of supporting teachers and accommodating the multiple constraints students face.

Despite substantial investment in education globally, governments continue to struggle with low student achievement. Over the past few decades, many developing countries have made impressive strides in increasing school enrolment, yet the anticipated learning gains have not always materialised (Angrist et al. 2021, Jenkins 2024). This persistent “learning crisis” highlights the urgent need for innovative solutions to transform education systems (World Bank 2018).

Efforts to boost student outcomes often focus on enhancing teacher effectiveness. This can involve upgrading teacher skills through training, refining pedagogical approaches, or providing incentives to boost motivation. Research shows that monetary incentives, like performance-based payments, can yield positive results in some contexts (Lavy 2009, Muralidharan and Sundararaman 2011, Duflo et al. 2012); however, these schemes can burden public budgets and become unsustainable in the long term. Recent initiatives have sought to reform traditional teaching practices through remedial education programmes (e.g. Banerjee et al. 2007, Banerjee et al. 2017, Marinelli et al. 2024), technology-aided instruction (Muralidharan et al. 2019, Beg et al. 2022), and standardised lesson scripts (Gray-Lobe et al. 2022).

In our research (Piza et al. 2024), we study an approach that gives teachers the autonomy to develop pedagogical innovations that are relevant to their context. The autonomy is expected to motivate teachers and add meaning to their job. Additionally, it leverages their knowledge of the local context to increase the relevance of pedagogical interventions – elements which have been shown to be effective in other contexts (Cassar and Meier 2018, Duflo et al. 2018, Rogger and Somani 2023). On the other hand, decentralising decision-making comes with certain risks, such as inefficiencies or reduced effort from local staff, particularly in settings with limited resources (Burgess et al. 2012, Banerjee et al. 2021).

What was the Pedagogical Innovation Project?

The Brazilian education system has long been marred by low student achievement, high repetition and dropout rates. Traditional pedagogical approaches, characterised by a rigid, centrally defined curriculum and a hierarchical teacher-student relationship, have limited the scope for innovation and adaptation of teaching methods to local, school-specific issues (Carvalho 2016).

In response to these longstanding challenges, the State Secretariat of Education of Rio Grande do Norte, one of Brazil's poorest states, implemented the Pedagogical Innovation Project (Projeto de Inovação Pedagógica). The project was designed to empower teachers by granting them the autonomy to introduce locally adapted pedagogical innovations. Unlike typically top-down educational reforms, the Pedagogical Innovation Project encouraged teachers to identify the unique challenges of their students and develop tailored solutions. The programme combined this autonomy with technical assistance and allocated funding to support operationalisation of the proposed activities.

The programme targeted the final grade of primary education (fifth grade), the first grade of lower-secondary education (sixth grade), and the first grade of upper-secondary education (tenth grade) due to their high rates of student repetition and dropout. Through seminars and with the support of a dedicated mentor, grade five, six, and ten teachers diagnosed their pedagogical challenges and designed context-specific projects to address them. Teachers were provided with continuous technical support during the project's design and implementation. In tandem, schools received funding to implement these projects, which ranged from about $7,500 to $11,000 USD – median of $139 per student or 3.6% of the average annual expenditure per student in Brazil (OECD 2016).

Our research studies the 2016 edition of the Pedagogical Innovation Project. In collaboration with the State Secretariat and the World Bank, we randomly invited 130 schools to participate in the programme among 299 eligible schools.

Significant gains in student learning and progression in grade six

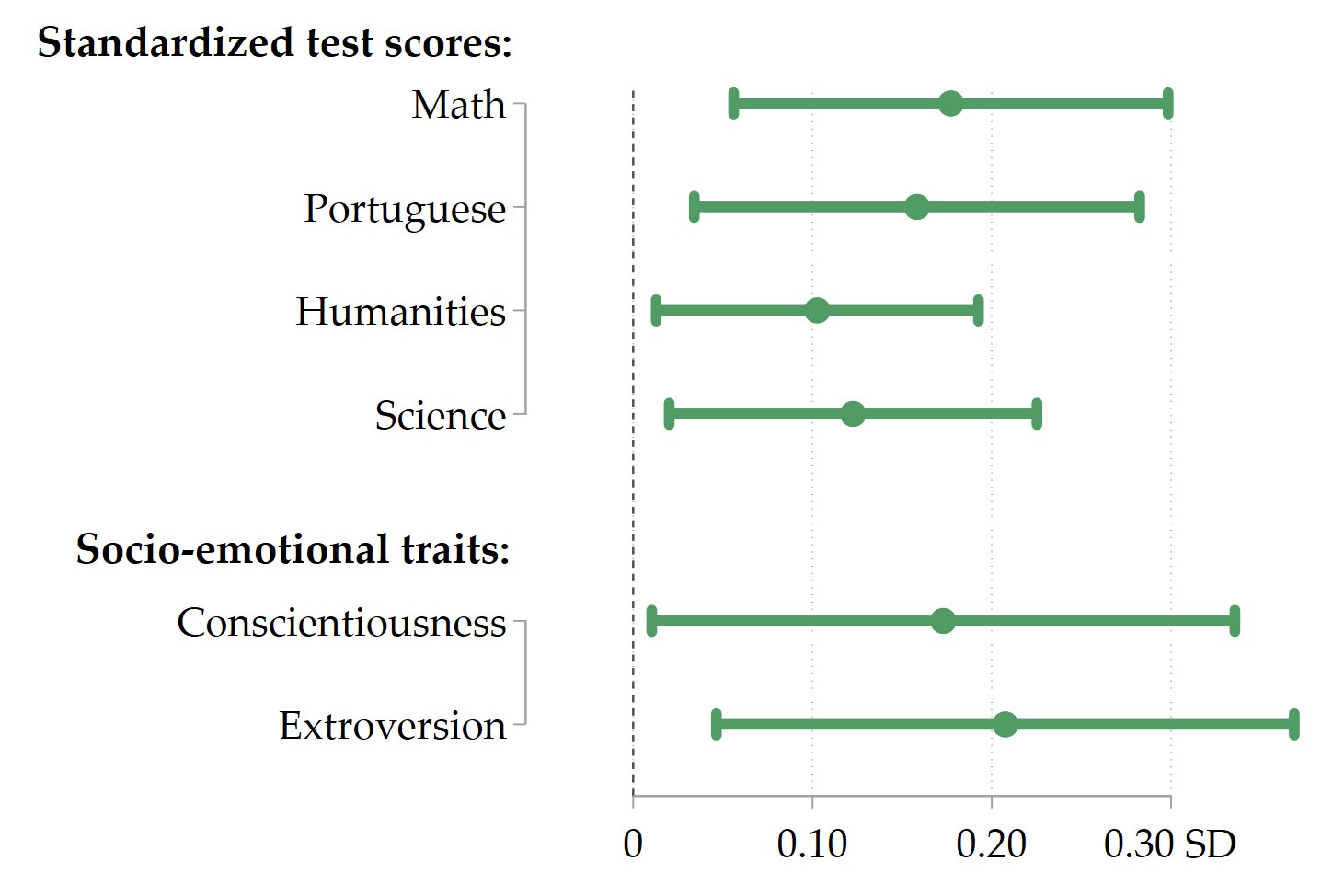

The Pedagogical Innovation Project mostly had effects for grade six students, a critical grade as children transition from primary to lower-secondary education. In this grade, the programme led to substantial increases in standardised test scores, with a 0.18 standard deviation improvement in maths, 0.16 standard deviation in Portuguese, 0.10 standard deviation in humanities, and 0.12 standard deviation in sciences (Figure 1 – upper panel). These learning gains are equivalent to approximately half an extra year of schooling (i.e. 0.36 year of schooling per $100 spent), demonstrating the programme's effectiveness with relatively modest financial investment.

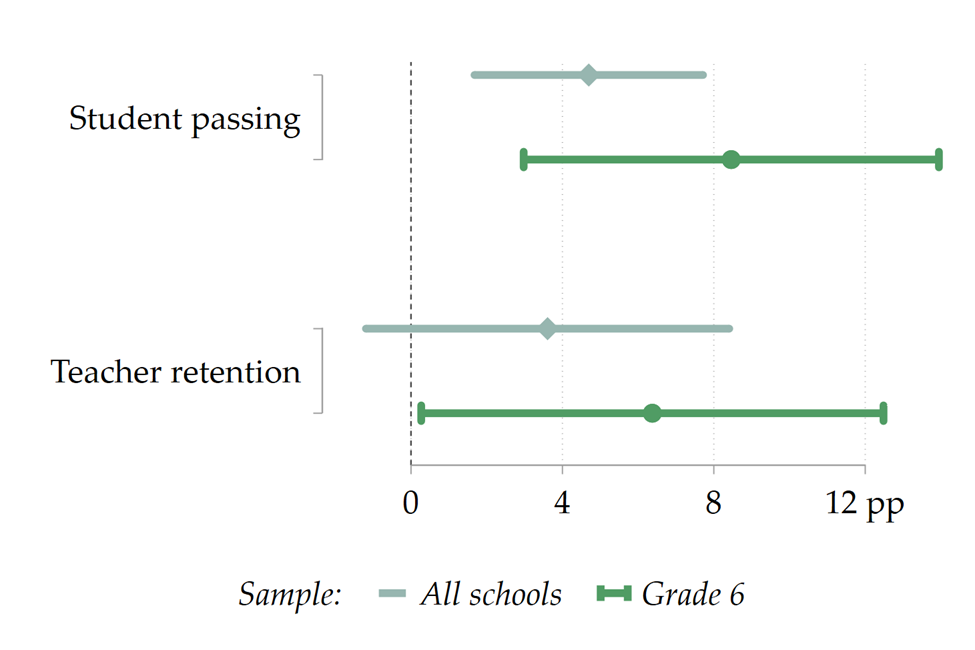

The percentage of students advancing to the next grade level increased by 4.70 percentage points across all targeted grades, i.e. a 6.6% improvement over the control group’s mean passing rate of 71%. However, the largest effects were observed in the sixth grade, where the passing rate increased by 8.46 percentage points – a 13% improvement compared to the control mean of 63.6% (Figure 2 – upper panel). These findings suggest that the programme not only enhanced student learning but also increased the likelihood of students advancing to the next grade level - both are crucial for long-term educational attainment.

Given the programme's emphasis on changing student-teacher interactions through the introduction of less traditional teaching methods, we also test whether the programme impacted students’ socio-emotional skills. In line with the other outcomes, we find positive results in grade six.

Conscientiousness increased by 0.17 standard deviation, and extroversion by 0.20 standard deviation (Figure 1 – bottom panel), indicating the programme contributed to the broader development of the students which is critical for academic achievement and labour market outcomes.

Figure 1: Impact on student learning and socio-emotional skills in grade six

Notes: Treatment effect estimates with 90% confidence interval. The coefficients are expressed in terms of standard deviations from the control group. Unit of observation: student; sample: schools treated at sixth grade. Full set of estimates reported in Table 1 and 4 of Piza et al. (2024).

Figure 2: Impact on student progression rates and teacher retention

Notes: Treatment effect estimates with 90% confidence interval. The coefficients are expressed in terms of percentage points from the control group. Unit of observation: school or teacher; sample in the legend. Full set of estimates reported in Table 2 and 3 of Piza et al. (2024).

Unpacking programme components and mechanisms

The distinct components of the programme were designed to be complementary to help achieve positive impacts. This aligns with growing evidence on the importance of complementarities between school inputs and teacher incentives in education (Mbiti et al. 2019, Gilligan et al. 2022). We try to unpack the relative importance of the different components and mechanisms.

Increasing teacher engagement: Teacher-led innovations likely fostered a sense of ownership and commitment among educators. Teacher retention increased by 6.4 percentage points in grade six, a 20.7% increase over the control mean (Figure 2 – bottom panel) – driven by schools with low retention rates at baseline.

Introduction of innovative sub-projects: Programme implementation varied across grades, but it was sixth-grade schools that managed to implement the projects at the highest rate.

Importance of complementarities: No spillover effects were found on seventh-grade progression rates, even though most sixth-grade teachers also teach in seventh grade. This provides suggestive evidence that the autonomy and support provided by the programme may have played an important role in keeping teachers engaged, especially in challenging environments, but may not necessarily spillover to other grades in the absence of the pedagogical projects. On the other hand, student outcomes are most impacted in schools where the impact on teachers were largest, those with low teacher retention at baseline. Taken together these findings point to important complementarities between the two core components.

Role of the grant: The average grant size does not have any predictive power on the quality of activity implementation and student outcomes. We do find that treatment schools were better able to disburse their regular government funding in the year following the evaluation, suggesting that the programme may have helped schools overcome administrative constraints to implement projects through the complementary technical assistance.

Lessons for education policy and practice

The study offers valuable insights for policymakers and educators seeking to improve educational outcomes. First, it provides novel evidence that teacher autonomy, when properly supported, can be a powerful tool for improving education delivery and enhancing student achievement. By allowing teachers to design and implement innovations of their choosing, the programme succeeded in boosting both cognitive and socio-emotional development in sixth grade, a crucial transitional year in the Brazilian education system.

Second, the programme underscores the importance of bundled educational policies that address the multifaceted constraints faced by students. The complementary nature of the programme’s components – teacher autonomy, technical assistance, and financial resources specifically earmarked to implement the project – appears to have been critical in achieving the observed positive impacts.

Finally, the Pedagogical Innovation Project’s emphasis on teacher-led, context-specific innovations offers a viable alternative to more standardised approaches to educational reform. While structured programmes and training initiatives have their place, empowering teachers to develop and implement their own solutions can be an effective strategy, even in low-capacity environments.

As countries around the world continue to grapple with the “learning crisis”, the lessons from the Pedagogical Innovation Project offer a promising path forward. By empowering teachers and providing them with the necessary support, policymakers can unlock the potential of educators and achieve lasting improvements in student learning and development.

References

Angrist, N, S Djankov, P K Goldberg, and H A Patrinos (2021), “Measuring Human Capital Using Global Learning Data,” Nature, 592(7854): 403-408.

Banerjee, A, R Banerji, J Berry, E Duflo, H Kannan, S Mukerji, M Shotland, and M Walton (2017), “From Proof of Concept to Scalable Policies: Challenges and Solutions, with an Application,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4): 73-102.

Banerjee, A, R Chattopadhyay, E Duflo, D Keniston, and N Singh (2021), “Improving Police Performance in Rajasthan, India: Experimental Evidence on Incentives, Managerial Autonomy, and Training,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13(1): 36-66.

Banerjee, A V, S Cole, E Duflo, and L Linden (2007), “Remedying Education: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments in India,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3): 1235-1264.

Beg, S, W Halim, A M Lucas, and U Saif (2022), “Engaging Teachers with Technology Increased Achievement, Bypassing Teachers Did Not,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(2): 61-90.

Burgess, R, M Hansen, B A Olken, P Potapov, and S Sieber (2012), “The Political Economy of Deforestation in the Tropics,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(4): 1707-1754.

Carvalho, J S de O (2016), “O Projeto de Inovação Pedagógica (PIP) e as práticas inovadoras dos professores da rede estadual do ensino médio no RN,” Universidade Estadual do Rio Grande do Norte.

Cassar, L, and S Meier (2018), “Nonmonetary Incentives and the Implications of Work as a Source of Meaning,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32(3): 215-238.

Duflo, E, M Greenstone, R Pande, and N Ryan (2018), “The Value of Regulatory Discretion: Estimates from Environmental Inspections in India,” Econometrica, 86(6): 2123-2160.

Duflo, E, R Hanna, and S P Ryan (2012), “Incentives Work: Getting Teachers to Come to School,” American Economic Review, 102(4): 1241-1278.

Gilligan, D O, N Karachiwalla, I Kasirye, A M Lucas, and D Neal (2022), “Educator Incentives and Educational Triage in Rural Primary Schools,” Journal of Human Resources, 57(1): 79-111.

Gray-Lobe, G, A Keats, M Kremer, I Mbiti, and O W Ozier (2022), “Can Education be Standardized? Evidence from Kenya,” The University of Chicago Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper 2022-68.

Jenkins, R (2024), “The Global Learning Crisis,” VoxDevTalk, https://voxdev.org/topic/education/global-learning-crisis.

Lavy, V (2009), “Performance Pay and Teachers' Effort, Productivity, and Grading Ethics,” American Economic Review, 99(5): 1979-2011.

Marinelli, H A, S Berlinski, and M Busso (2024), “Remedial Education: Evidence from a Sequence of Experiments in Colombia,” Journal of Human Resources, 59(1): 141-174.

Mbiti, I, K Muralidharan, M Romero, Y Schipper, C Manda, and R Rajani (2019), “Inputs, Incentives, and Complementarities in Education: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(3): 1627-1673.

Muralidharan, K, A Singh, and A J Ganimian (2019), “Disrupting Education? Experimental Evidence on Technology-Aided Instruction in India,” American Economic Review, 109(4): 1426-1460.

Muralidharan, K, and V Sundararaman (2011), “Teacher Performance Pay: Experimental Evidence from India,” Journal of Political Economy, 119(1): 39-77.

OECD (2016), Education at a glance 2016, Paris, OECD Publishing, p. 508.

Piza, C, A Zwager, M Ruzzante, R Dantas, and A Loureiro (2024), “Teacher-Led Innovations to Improve Education Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Brazil,” Journal of Public Economics, 234: 105123.

Rogger, D, and R Somani (2023), “Hierarchy and Information,” Journal of Public Economics, 219: 104823.

World Bank (2018), World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise.