School-based life skills classes can change attitudes, strengthen social connections, and help girls assert more control over their lives while staying in school

Throughout the developing world, women and girls face severe limitations on their ability to exercise agency in important life domains, including the pursuit of education, the choice of work, and the decision of when to marry and have children. Limitations on agency have remained stubbornly persistent even as other dimensions of women's and girls' welfare have shown rapid improvements. For example, in this study's setting in Rajasthan, India, net primary school enrolment rates for girls have more than tripled since the mid-1980s; despite this, over 90% of adult women in our study report that a wife should always obey her husband, and 17% of our study participants are married at an average age of eleven.

How do we change the societal norms that disadvantage girls? A popular prescription amongst economists is to pay households to treat their daughters better, but the jury is still out on whether extrinsic incentives can change intrinsic norms and motives. While out-of-school efforts to empower girls such as Save the Children’s Safe Spaces and BRAC’s ELA programme are effective in helping participating girls change their lives, they struggle with low participation (Buchmann et al. 2017, Bandiera 2019, 2020). In-school efforts that focus on changing one targeted concept such as the value of education (Jensen 2010), the importance of gender equity (Dhar et al. 2020), or how to negotiate (Ashraf et al. 2020), are effective in imparting that lesson, often with meaningful consequences for education.

Can a multifaceted life skills programme, delivered in school, help girls take control of their lives? This study explores whether it is possible to increase girls' agency and stimulate the development of more equitable gender norms in a setting of intense gender disparity and, through these attitudinal changes, increase girls' schooling attainment. In our research Edmonds et al. (2020), we partnered with the non-governmental organisation, Room to Read, to evaluate a life skills education and mentoring programme delivered in Rajasthan, India.

Evaluating a school-based life skills programme

The intervention

The Girls’ Education Programme (GEP) is built around a life skills curriculum emphasising the development of ten skill categories: self-confidence, expressing and managing emotions, empathy, self-control, critical thinking, decision-making, perseverance, communication, relationship building, and creative problem solving. The curriculum is implemented in school by a social mobiliser (SM), a trained woman from the area who has completed secondary school. Every other week, she conducts life skills sessions with participants for one class period of the school day. The sessions are aimed at helping girls troubleshoot difficulties in their lives, develop long-term schooling and career goals, enhance their agency, boost their self-confidence, and develop peer solidarity.

Evaluation design

The overall sample of our evaluation comprised of 2,459 girls from 119 schools in Ajmer, Rajasthan, with 60 schools receiving the GEP. The evaluation began in 2016 when the girls where in 5th grade. The GEP began in 6th grade, and most of our data collection concluded after 7th grade in 2018, although we were also able to collect some school records through the latter half of 2019, after girls had transitioned to high school. The evaluation principally relied on qualitative and quantitative household surveys and included extensive life skills measures, demonstration tasks of those life skills, and cognitive testing.

Findings

- Engagement in GEP is high. The target number of GEP classes was offered in all treatment schools, with 85% of girls that were offered the programme remaining engaged through 7th grade, and with the modal girl attending all the life skills classes offered.

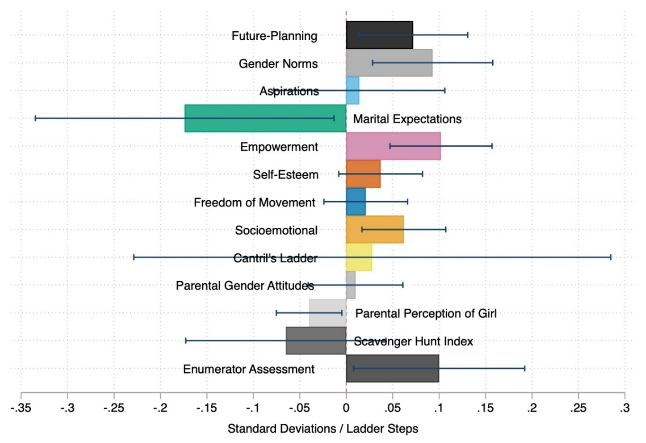

Figure 1

- GEP improved girls’ understanding and expression of life skills (shown in Figure 1). On the survey-based life skills outcome measures, girls in the GEP reported improvements in social and emotional support and empowerment. They also demonstrated more equitable gender norms in terms of their perceptions of the importance of girls’ education, and they showed clear evidence of increases in future planning.1 The shifts in self-reported life skills are corroborated by assessments by enumerators and parents, suggesting that the changes were observable to adults with whom these girls interacted. In addition, further robustness checks suggest that these results are not driven by social desirability bias, or a desire by girls to report the ‘right’ responses.

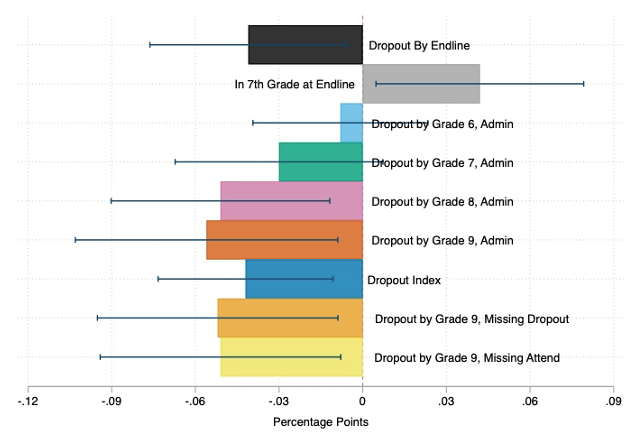

Figure 2

- GEP reduced dropout and improved grade progression (shown in Figure 2). The average dropout rate in the group receiving GEP was 25% lower than the dropout rate in the comparison group at endline. Girls in GEP were also 4.2% more likely to have progressed to the appropriate grade level. In addition, reductions in dropout persist (as observed in administrative data) through the start of 9th grade, a point at which girls frequently drop out, and the size of the dropout effect remains consistent.

- But some important dimensions of girls’ lives did not change. Many important aspects of our subjects’ lives do not appear to have been impacted by GEP in the time period observed. Though girls are more likely to stay enrolled in school, they do not attend more frequently. They do not study more or do better in testing (as measured in school by their teachers and at home by our enumerators). They also do not appear to be less likely to engage in child labour, and the intervention does not appear to reduce child marriage.

Girls can change their lives, but within limits

Our findings suggest that a school-based life skills and mentoring programme generates persistent improvements in life skills for adolescent girls, as measured approximately six months after the programme ended, and reduces school dropout through the beginning of 9th grade.

The decline in dropout we observe could reflect multiple channels: increased agency on the part of girls, increased socioemotional support from their peers, and/or increased aspirations. However, further exploration suggests that there is little evidence of diverging preferences between girls and parents around education – both express a strong preference for secondary education for girls – implying that girls do not deploy their enhanced agency to negotiate vis-à-vis parents around their enrolment decision. In addition, there is little evidence that the treatment meaningfully enhanced girls’ aspirations.

The growth in socioemotional support provides an interesting explanation for why we might see a reduction in dropout without a rise in attendance or academic performance. In our qualitative fieldwork, one particularly insightful head-teacher remarked that the GEP programme was effective in inducing girls to stay in school to be with their friends without any improvements in their performance, and our results are consistent with her experience. This pattern suggests that harnessing social relationships already present within schools may be a promising strategy for other programmes targeting the development of life skills. However, the absence of significant effects on other dimensions of girls’ welfare also suggests that there may be limits to the potential positive effects of enhanced life skills in contexts in which girls’ agency over other life domains is severely circumscribed.

References

Ashraf, N, N Bau, C Low and K McGinn (2020), “Negotiating a better future: How interpersonal skills facilitate inter-generational investment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, 1095-1151.

Bandiera, O, N Buehren, M P Goldstein, I Rasul and A Smurra (2019), “The economic lives of young women in the time of Ebola: Lessons from an empowerment program”, The World Bank.

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, M Goldstein, S Gulesci, I Rasul and M Sulaiman (2020), “Women's empowerment in action: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(1): 210-259.

Buchmann, N, E Field, R Glennerster, S Nazneen, S Pimkina and I Sen (2017), “Power vs money: Alternative approaches to reducing child marriage in Bangladesh, a randomized control trial”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Dhar, D, T Jain and S Jayachandran (2020), “Reshaping adolescents' gender attitudes: Evidence from a school-based experiment in India”, NBER Working Paper 25331.

Edmonds, E, B Feigenberg and J Leight (2020), “Advancing the agency of adolescent girls”, NBER Working Paper 27513.

Jensen, R (2010), “The perceived returns to education and the demand for schooling”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(2): 515-548.

Endnotes

1 These observed shifts correspond to increases of 0.05 to 0.1 standard deviations in life skills indices relative to the control group.