Lowering the cost of accessing secondary school proved to be a powerful tool in curtailing early marriage in Niger, and had a host of other benefits for girls

While child marriage rates have been halved in South Asia in the last 25 years, the decline in Sub-Saharan Africa has been more modest. One in three girls is still married as a child in the region (UNICEF 2018). Early marriage has a large detrimental effect not only on the health, education, and labour market outcomes of women but also on her children. In this context various policymakers have outlawed child marriage, though with mixed impact (Wilson 2021, Diarra 2019, Maswikwa 2015). Given the mixed evidence regarding the impact of increased participation on child marriage (Alam et al. 2011, Baird et al. 2011, Angrist et al. 2002 Duflo et al. 2015, Duflo et al. 2021) the question of whether governments should prioritise educational investment as a response to child marriage remains open. Recent evidence in Niger suggests that lowering financial barriers to secondary education for rural girls is an effective policy lever to reduce child marriage.

Niger has the highest rates of child marriage in the world

In Niger, 76% of women aged 20-24 were married before the age of 18, with 28% married before age 15, representing the highest levels of child marriage globally. Although there has been substantial progress in primary school enrollment, post-primary education remains limited for girls: only 36% start middle school (grades 6-9), and just 14% complete it. Despite tuition-free middle school, accessing secondary education involves significant direct and opportunity costs for households, especially in remote areas. Given that the network of middle schools is sparse (83% of Niger’s population is rural), most families reside in villages without secondary schools. For these families, sending daughters to school often means incurring high transportation costs or paying for a host family near the school, in addition to the expenses for school supplies and uniforms. Moreover, enrolling a daughter in secondary school can entail considerable opportunity costs, as girls may usually contribute to household chores or economic activities.

How did Niger’s government try to reduce child marriage?

In this context, the Ministry of Population, the Ministry of Women’s Promotion and Child Protection, and the Ministry of Secondary Education in Niger designed an intervention to eliminate the direct costs of middle school with the objective of reducing child marriage. Rural girls from underprivileged backgrounds were offered a three-year scholarship from October 2017 to June 2020. Amounting to USD $306 per year, the scholarship is meant to cover all out-of-pocket schooling expenses. A key feature of this programme is its minimal conditionality: girls receive the monthly payments as long as they remain enrolled and do not repeat a grade more than once. Such conditionality not only reduces monitoring costs, but also allow girls with lower academic achievement to stay in school – and, potentially, to stay away from marriage.

To measure the intervention's impact, we conducted a randomised controlled trial involving 2,400 adolescent girls from 285 rural villages without middle schools. These villages were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 1) a control group, where no scholarships were offered; 2) a full treatment group, where all eligible girls received scholarships; and 3) a partial treatment group, where scholarships were randomly offered to 50% of the eligible girls. This two-stage randomisation design enables us to assess both the direct impacts on scholarship recipients and the indirect effects on their peers. Data was collected in August 2020, following the completion of the three-year intervention.

How did scholarships affect girls in Niger?

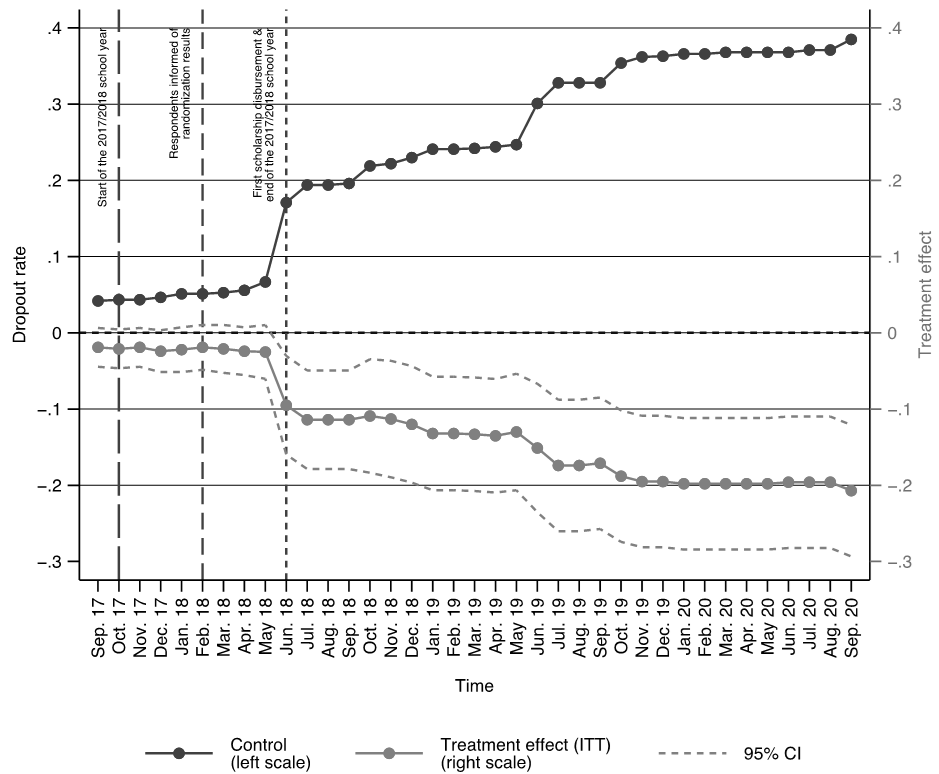

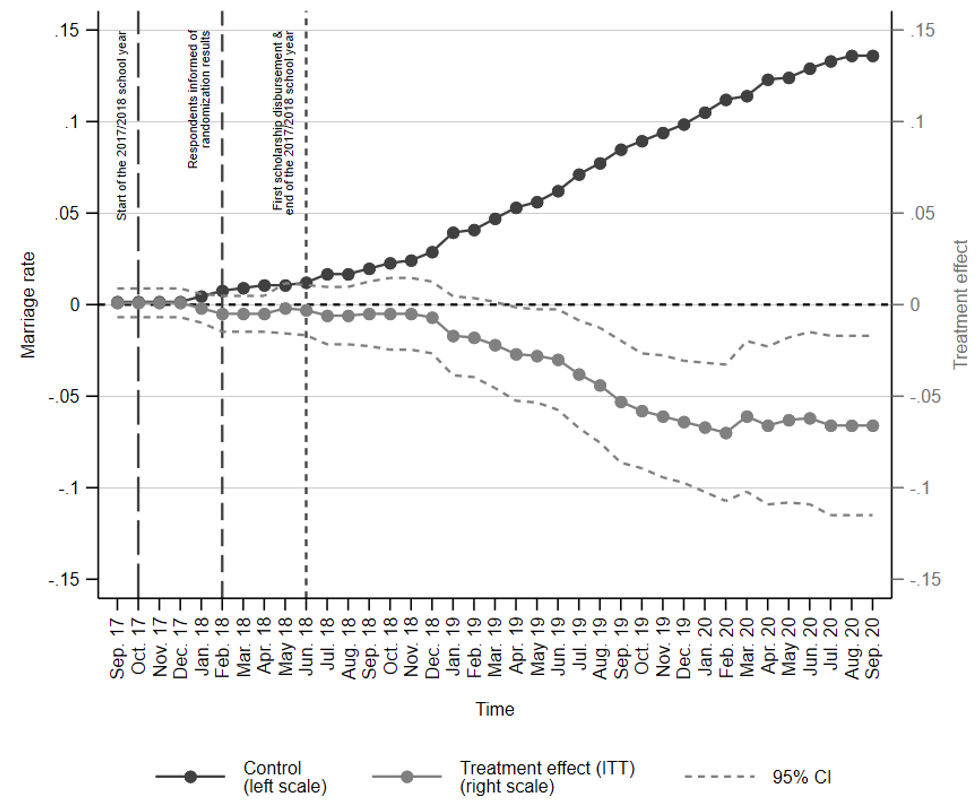

We find that TFE transformed girls’ lives in important dimensions. It reduced the likelihood of dropping out of school and of being married by endline by 50% (Figure 1 and 2). A simple back of the envelope calculation suggests that, for the subset of girls whose length of schooling increases as a result of the scholarship, each additional year spent in secondary education would reduce the probability of marriage by 19 percentage points. The programme also improved girls’ well-being as life satisfaction increased by 0.25 standard deviations. Although it was too early to assess impacts on fertility behaviour by endline — with only 3% of girls in the control group having been pregnant — the perceived ideal age for first childbirth rose by one year. These findings suggest that we may see a reduction in early childbearing in future follow-ups, which would represent a significant health benefit given the risks associated with adolescent pregnancy.

Figure 1: The impact of scholarships on girl’s dropout rates

Source: Giacobino et al. (forthcoming). Notes: This figure depicts the impact of the intervention on girls’ dropout rate, which is measured every month from the intervention start date (using information about the date of their dropout).

Figure 2: The impact of scholarships on girls’ marriage rates

Source: Giacobino et al. (forthcoming). Notes: This figure depicts the impact of the intervention on girls’ marriage rate, which is measured every month from the intervention start date (using information about the date of their first marriage). To do so, we represent the marriage rates in the control group (in black) and in the treatment group (in grey).

We argue that the effects on marriage are unlikely to stem solely from an incapacitation effect— whereby schooling reduces the time available for building relationships. In particular, we observe notable improvements in the girls’ aspirations. Girls in the treatment group are more likely to be willing to complete secondary and higher education, as well as to have a modern occupation. We also find evidence that the programme modernised girls’ preferences. We find an increase in the ideal age for marriage and ideal education levels for future sons and daughters. Interestingly, the intervention also increased parents’ aspirations for their daughters: parents of treated girls expressed desires for their daughters to marry later, pursue extended education, and choose modern occupations. These changes suggest that parental preference for early marriage can respond positively to financial support for their daughter’s education. The impacts on the aspirations and preferences of both girls and their parents indicate that the programme is likely to transform girls’ lives well beyond the end of the programme.

Furthermore, our two-stage randomisation design allows us to show that the program's overall impact was unambiguously positive. We observe no adverse effects on the age at first marriage among the eligible girls’ sisters. Furthermore, we detect no externalities on eligible girls who did not receive the scholarship in villages where 50% of girls received the financial support. Similarly, we find no impact on ineligible girls in treated villages or neighboring villages.

Crucially, our paper shows that even in contexts characterised by strong conservative gender norms, low female empowerment, poor quality education, and limited labour market opportunities, lowering the cost of post-primary education encourages households to keep their daughters in school and delay marriage. We show that fostering girls’ enrolment in secondary school may be a powerful policy lever to reduce early marriage in context where bans have proved ineffective.

References

Alam, A, J E Baez, and X V Del Carpio (2011), "Does cash for school influence young women's behavior in the longer term? Evidence from Pakistan", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5669.

Angrist, J, E Bettinger, E Bloom, E King, and M Kremer (2002), "Vouchers for private schooling in Colombia: Evidence from a randomized natural experiment", American Economic Review, 92(5): 1535-1558.

Baird, S, C McIntosh, and B Özler (2011), "Cash or condition? Evidence from a cash transfer experiment", The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4): 1709-1753.

Diarra, A (2019), "Lutter contre les mariages précoces par l’autonomisation des filles", Etudes et Travaux du LASDEL, 126.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, and M Kremer (2015), "Education, HIV, and early fertility: Experimental evidence from Kenya", American Economic Review, 105(9): 2757-97.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, and M Kremer (2021), "The Impact of Free Secondary Education: Experimental Evidence from Ghana", Working Paper.

Giacobino, H, E Huillery, B Michel, and M Sage (forthcoming), "Schoolgirls, Not Brides: Education as a Shield against Child Marriage", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Maswikwa, B, L Richter, J Kaufman, and A Nandi (2015), "Minimum marriage age laws and the prevalence of child marriage and adolescent birth: evidence from sub-Saharan Africa", International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41(2): 58-68.

Wilson, N (2021), "Child Marriage Bans and Female Schooling and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Natural Experiments in 17 Low-and Middle-Income Countries", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(3): 449-477.