A community-led intervention in Northern Nigeria significantly reduced rates of child marriage in adolescent girls by changing entrenched, normative behaviour

When problems are global in scale, it is tempting to look for global solutions – interventions that can be implemented at scale. Yet problems that are rooted in communities may require solutions that are equally deeply rooted. Child marriage could be one such problem, and our new research shows that a community-led intervention in Northern Nigeria significantly reduced rates of child marriage in adolescent girls by changing entrenched, normative behaviour (Cohen et al. 2023).

As many as 12 million girls marry before the age of 18 every year, most of them from low- and middle-income countries (UNICEF 2022). The most vulnerable girls are those whose parents cannot invest in education or training, even if such resources are available (Parsons et al. 2015). At the same time, marrying early worsens a girls’ health, likelihood of labour force participation, and increases her risk of experiencing violence.

Child marriage also creates a vicious cycle. At the community-level, child marriage becomes entrenched; parents might want to wait until their daughters are older, but with few options – and many girls of the same age already marrying – they do what they think is best for their girls. In northern Nigeria, where school systems are failing and alternatives to school are few and far between, roughly 80% of girls marry before age 18 (Save the Children 2021).

Pathways to Choice, an intervention to delay child marriage and increase education, is an intervention tailor-made for northern Nigeria. Pathways intentionally targets all unmarried, out-of-school girls, providing social support through mentored girls’ clubs and offsetting costs for girls who return to school. Pathways is run by the Centre for Girls Education (CGE), which is based in Zaria, Nigeria, and managed by locally born and raised women. Started in 2016, Pathways was refined through participatory community engagement, and evaluated with a cluster-randomised control trial in 18 communities from 2018 to 2020.

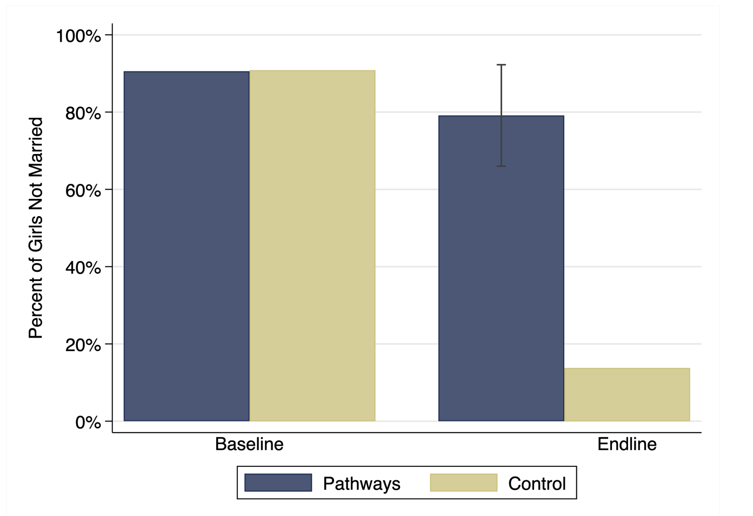

Figure 1: The impact of “Pathways to Choice” on child marriage

The first result to emerge from this evaluation is that Pathways works - early marriage rates for adolescent girls fell by 64 percentage points in treatment communities. The question is: why?

Pathways accomplishes two key things. First, it lowers the costs and increases the benefits for parents when it comes to sending their daughters to school. Second, through careful community outreach and the deliberate enrolling of all girls in a village, Pathways enables changes to happen for entire groups at once, significantly increasing its overall effect.

Pathways starts with nine months of meetings in mentored girls’ clubs, which focus on interactive and nonformal remedial education and the building of social ties and life skills. In the second year, Pathways defrays the practical costs of attending either school or vocational training, including fees, uniforms, and textbooks. At the same time, the girls can apprentice in village-based shops created by CGE.

These methods work; in addition to delaying early marriage, Pathways increases the likelihood that a girl is enrolled in school at the end of the second year from 10% to nearly 80%, with disproportionate benefits for the most disadvantaged girls.

Pathways’ whole community focus begins before the first girls’ meeting ever occurs. CGE’s team starts by meeting with village and religious leaders and hosts regular workshops to discuss support in the Quran and Hadith for girls’ education. Working with village elders, CGE seeks out all girls aged 12 to 17 who are unmarried and out-of-school and enrolls them in Pathways.

Evidence from the RCT suggests that community dynamics are crucial to Pathways’ success. Conditional on a girl’s own age, Pathways is less effective when that girl’s peers are older at the time when the programme begins. Younger girls face less pressure to marry, giving Pathways time to work, but these results also suggest that what a girl sees her cohort-mates doing meaningfully impacts her and her parents’ own decisions. Similarly, Pathways is more effective for a girl when her sisters are also enrolled.

Pathways is not cheap, with a moderately high upfront cost of implementation relative to interventions like providing school uniforms or textbooks alone. Yet, even after only two years, the evidence suggests the lifetime benefits of the programme more than outweigh the cost. To measure this, we calculate the net present value of the lifetime benefit of the programme to the participant based on estimates of the returns to education and compare it to programme costs. The program has a benefit-cost ratio of 2.41, comparable to many cheaper programmes according to a recent report (Field et al. 2016).

Pathways shows that complex, bundled problems – like child marriage – may respond best to complex, bundled interventions. Without education and vocational training, all the sensitisation in the world does not give girls a practical alternative to child marriage. If only part of a community is targeted, girls who attend school may be singling themselves out as strange and different, even when resources are available.

To date, we only know the results of the programme after two years; in the future, we hope to better to understand how the effects of Pathways evolve over time and whether they create community-level change. All the same, the results of the impact evaluation suggest that locally tailored programmes, with activities that surround a problem in concert, may be well worth the cost.

Note: The 2018-2020 Pathways initiative was designed and led by the Centre for Girls Education and implemented with the help of Hallmark Initiative and the Isa Wali Empowerment Initiative. The project and evaluation were funded by the Ford Foundation. The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own, and do not represent any other individuals or organisation.

References

Cohen, I, M Abubakar, and D Perlman (2023) “Pathways to Choice: A Bundled Intervention against Child Marriage.” UC Berkeley: Center for Effective Global Action. http://dx.doi.org/10.26085/C31C71 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/33j1k1k4.

Field, E, R Glennerster, N Buchmann, and K Murphy (2016), “Cost-benefit analysis of strategies to reduce child marriage in Bangladesh.” Technical report, Bangladesh Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center.

Parsons, J, J Edmeades, A Kes, S Petroni, M Sexton, and Q Wodon (2015), “Economic impacts of child marriage: A review of the literature.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 13(3): 12-22.

Save the Children (October 2021), “State of the Nigerian girl report: An incisive diagnosis of child marriage in Nigeria.” Available at https://nigeria.savethechildren.net/research-reports.

UNICEF, “Child marriage around the world: Infographic.” Last accessed: 19 July 2022. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/stories/child-marriage-around-world