Disbursing microfinance loans through mobile money accounts empowers female entrepreneurs to resist pressure to share loans with others

Editors’ note: To know more about women’s empowerment through microfinance loans, read our VoxDevLit on Microfinance.

Most working women in developing countries are self-employed,1 running their own micro-enterprises. These enterprises often make little profit and experience minimal growth, if any. This comes despite evidence showing that the rate of return to capital for small enterprises is quite high (De Mel et al. 2008). For women in particular, social pressures to share money have been shown experimentally to be one potential dampener of business investment (Jakiela and Ozier 2016, Squires 2018). Evidence from field experiments also highlights the importance of pressure to share money with family for female enterprise growth: In circumstances where women are not subject to family sharing pressure, either because they can hide money or they own the only household business, women are able to expand their businesses in response to grants and loans (Bernhardt et al. 2019, Fiala 2017). Additionally, when grants are given in-kind instead of as cash, women are able to increase the size and profitability of their businesses (Fafchamps et al. 2014).

Importantly, social-sharing norms have been shown to depend on the form money is in, with cash subject to sharing pressure, while savings in a bank account or in a business not subject to such pressures (Anderson and Baland 2002, Platteau 2000). This suggests that changing the form that business loans are given in, away from cash, could facilitate the growth of female-owned enterprises by reducing pressure to share the loan with others.

New evidence from Ugandan female entrepreneurs

In a recent paper (Riley 2020), I examine whether changing the form that a microfinance loan is disbursed in, from cash to directly into a mobile money account, enables higher investment in women’s businesses and increases their profits as a result. Second, I test whether household sharing pressure can explain why disbursing loans through mobile money enables more female enterprise growth.

I do this using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 3,000 female microfinance clients of BRAC, one of the largest NGOs in the world, in urban Kampala, Uganda. In this experiment, women taking out a loan from BRAC were individually randomised equally into one of three treatments:

- Mobile Account: labelled mobile money account for the business + loan as cash

- Mobile Disbursement: labelled mobile money account for the business + loan on the mobile money account

- Cash: loan as cash

No other features of the microfinance loan products were changed, and repayments continued to be made weekly at group meetings in cash. These loans were typical microfinance products, with an average loan size was $400, repaid over nine months at a 40% annual interest rate. Women were individually liable for repaying their loan, though the microfinance group had some say in who was given a loan.

All of these clients already had a business verified by BRAC, and the majority of the businesses were inventory focused, selling fruit and vegetables, household goods, and second-hand clothes and shoes. Prior to receiving the loan, on average, the women made US$ 100 of profit per month through their business and contributed 40% of household income. Two-thirds of the women were married, and for married women, 60% of their spouses also had a business of their own.

Notably, 97% of my sample had used mobile money before and mobile money services were an extremely widespread and established technology in Kampala, so the introduction of a new technology is not being examined.

Receiving a loan on a mobile money account improves business and household outcomes

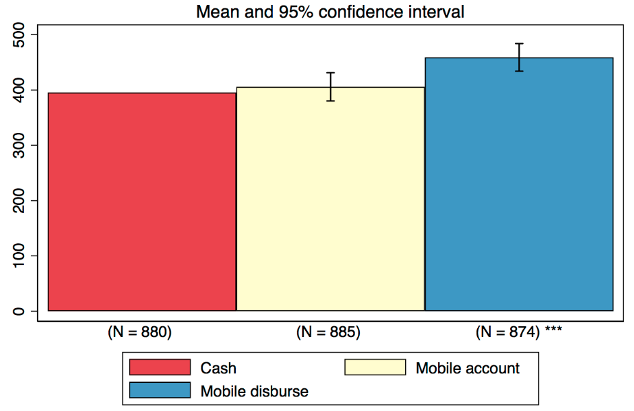

I find that eight months after the microfinance loan was disbursed, those in the Mobile Disbursement treatment make 15% higher profits and have 11% higher values of business capital invested in their businesses, compared to the control Cash group (see Figure 1). This improvement in business performance translates into benefits for the household as a whole, with both income and consumption 7% higher in the Mobile Disbursement group compared to the Cash group. I do not find any effects from the Mobile Account treatment, with the mobile money account only used by 13% of the women given them. Hence, the loan must be directly deposited into the mobile money account by BRAC for there to be beneficial impacts.

Figure 1 Monthly business profits ('000 Ugandan shillings)

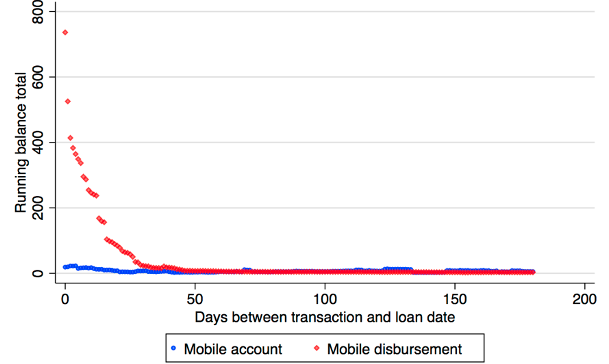

Using administrative data from the mobile money provider, I see that the mobile money accounts were primarily used to store the loan safely. The balance on the account was drawn down over time in an average of five withdrawals as needed for business investment, rather than the accounts being used for deposits (see Figure 2). As a result, more of the loan ends up in the woman’s business. I examine the reasons for this below.

Figure 2 Average mobile money account daily balance ('000 Ugandan shillings)

Loans disbursed on a mobile money account are less subject to sharing pressure from the spouse

I examine whether self-control difficulties or sharing pressure is the mechanism which explains my findings by looking at heterogenous treatment effects. I do this by constructing pre-specified indices of self-control difficulties and sharing pressure at baseline. The self-control index captures present bias and impatience, measured by an incentivised task, and whether the woman was saving for her business. The sharing pressure index captures an incentivised measure of willingness to hide money from the spouse, whether the woman is married, whether another household member has a business, and a self-reported measure of pressure to share money with family.

I see that the benefits of the Mobile Disbursement treatment are concentrated in women who experienced sharing pressure: women subject to the greatest pressure to share money with others at baseline see a 24% increase in business investment and 25% increase in profit from the Mobile Disbursement treatment. There is no effect of the Mobile Disbursement treatment for those who didn’t experience sharing pressure at baseline. I see no evidence of heterogeneous treatment effects by the self-control index.

Women report giving less money to others immediately after getting their loan in the Mobile Disbursement group, again validating sharing pressure as the channel through which the treatment has an effect on business investment. I do not see any evidence of backlash from the spouse in terms of how much money he transfers to her, and women report increases in empowerment in the form of more decision-making power within the household, better control over their funds, and fewer financial worries.

Why don’t women deposit the loan on the mobile money account themselves?

A key question from my study is: if the benefits from storing the loan on a mobile money account are so large, why don’t women in the Mobile Account group deposit the loan into such an account themselves? I explore three potential explanations for this.

First, I check for learning effects from observing the benefits to others by using the time dimension of the study. Since women were randomised into treatments upon loan application, women applying for a loan later on in the study were more likely to have observed other women in their group receive the Mobile Disbursement treatment. However, I see no change in the amount deposited by the Mobile Account group into their account over time. I also examine if women in the Mobile Disbursement group deposit a subsequent loan on the mobile money account, again seeing no evidence they do. This suggests learning is not occurring, potentially due to the noisiness of microfinance profits.

Second, I consider social norms as an explanation. It is possible that going to an agent yourself and depositing some of the loan would be seen as trying to get around sharing norms, in a way that having money deposited on your behalf does not. However, the spouse would have no way to differentiate between the woman or BRAC depositing the loan on the mobile money account, and given women engage in high rates of hiding of money , this seems unlikely as an explanation, though I cannot rule it out.

Third, I consider whether it’s more costly to deposit the loan yourself. However, transaction costs in terms of finding an agent are very low, with 50% of the sample living within a five-minute walk of an agent. This makes it unlikely that transaction costs could entirely explain why women don’t deposit the loan themselves, though again I cannot rule it out.

The most likely explanation for why women don’t make the deposit themselves is behavioural default effects, with the manner in which the loan is initially provided sticking. Women in the Mobile Account group therefore keep the loan as cash. Women in the Mobile Disbursement group keep it in the mobile money account until needed, resulting in less being shared with family and more ending up in their businesses. This fits with other studies that have shown powerful impacts on saving rates due to the default manners in which funds are given (Blumenstock et al. 2018, Brune et al. 2018, Somville and Vandewalle 2018).

Policy implications: Digital payments can benefit women entrepreneurs

Mobile money services are immensely popular and widespread in Uganda, and use is growing across sub-Saharan Africa. My study suggests that switching the typical disbursement of a microfinance loan from cash to a private, secure account that women can easily access has large benefits for their businesses and households. Microfinance organisations also stand to benefit from lower cash handling costs and increased safety by moving to digital disbursement. This study also shows the popularity of disbursement of microfinance loans through mobile money accounts, with 80% of women offered consenting to receive it in that way. It is therefore an accepted, low cost, and easy change to the current default of disbursing loans as cash. More generally, organisations distributing cash to women should consider digital modes of disbursement in order to enable women to better control the funds.

While my study shows the success of digital disbursement of microfinance loans in an urban context, the effects in rural areas may be different. More research is also needed to understand the optimal balance between easy access to the account and sufficient obstacles to deter sharing.

Editors’ note: A version of this column first appeared in World Bank’s Development Impact blog.

References

Anderson, S and J Baland (2002), “The Economics of ROSCAs and Intrahousehold resource allocation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3): 963–995.

Blumenstock, J, M Callen and T Ghani (2018), “Why Do Defaults Affect Behavior? Experimental Evidence from Afghanistan”, American Economic Review, 108(10): 2868–2901.

Brune, L, E Chyn and J T Kerwin (2018), "Pay Me Later: A Simple Employer-based Saving Scheme".

De Mel, S, D Mckenzie and C Woodruff (2008), “Returns to capital in microenterprises: evidence from a field experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4): 1329–1372.

Fafchamps, M, D Mckenzie, S Quinn and C Woodruff (2014), “Microenterprise growth and the flypaper effect: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana”, Journal of Development Economics, 106: 211–226.

International Labour Organisation, 2021, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/.

Jakiela, P and O Ozier (2016), “Does Africa Need a Rotten Kin Theorem? Experimental Evidence from Village Economies”, Review of Economic Studies, 83(1): 231–268.

Platteau, J P (2000), Institutions, social norms and economic development, Harwood Academic.

Riley, E (2020), "Resisting social pressure in the household using mobile money: Experimental evidence on microenterprise investment in Uganda".

Somville, V and L Vandewalle (2018), “Saving by Default: Evidence from a Field Experiment in India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(3): 39–66.

Squires, M (2018), Kinship Taxation as an Impediment to Growth: Experimental Evidence from Kenyan Microenterprises.

Endnotes

1 Source: International Labour Organisation (https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/)

2 In a game, 50% of women would rather have $2 themselves than their spouse have $8.