Expanding professional networks for growth-oriented female entrepreneurs improved business outcomes such as innovation, business practices, and profits

Gender gap in entrepreneurship

Despite being the only region in the world where there are more female entrepreneurs than men, the vast majority of female-owned businesses in Sub-Saharan Africa are microenterprises. In addition, women’s owned businesses earn 34% lower profits than male-owned ones. Understanding the constraints faced by female entrepreneurs is therefore vital for fostering economic growth.

Recent studies have shown that interfirm relationships and access to professional networks can be important drivers of business success (Ashraf et al. 2019, Kanter 1994, Cai and Szeidl 2017). Building business networks and forming collaborations can help firms adopt new business practices, expand market reach, innovate, and gain new customers (Kanter 1994, Cai and Szeidl 2017). However, because female entrepreneurs tend to have smaller networks and are less connected to other firms (World Bank Group 2019), they are more likely to rely on their friends and family members and have less access to high-quality entrepreneurs with whom to network. As a result, increasing networking opportunities among female entrepreneurs may help firms grow. However, past interventions that aim at expanding business networks mainly considered male entrepreneurs (Cai and Szeidl 2017). There is still limited knowledge about how creating interfirm relationships can contribute to the growth of female-owned businesses.

Role of networking for female entrepreneurs in Ghana

Using a field experiment in Ghana, we study (Asiedu, Lambon-Quayefio, Truffa and Wong 2023) how access to online networking opportunities affects firm performance. We focus on a sample of 1,771 female entrepreneurs who have applied to the COVID-19 Stimulus Fund offered by our partner NGOs with the aim of supporting high-growth and sustainable firms at the height of the pandemic. It is important to note that while most of the firms in our sample are small microenterprises, they are more growth-oriented than the typical small firm due to the application process. Over 30% of the women in our sample hold university degrees and 80% of the firms are registered.

Details of the intervention

We randomly assigned the female entrepreneurs to two treatment arms and a control group. In the first treatment arm, women were assigned into networking groups, which comprised of eight entrepreneurs on the WhatsApp platform, and engaged in two rounds of weekly networking activities. Each week, one member was assigned to meet virtually with another group member. In addition, a directory consisting of all entrepreneurs in the treatment group with their contact information was made available to facilitate the networking process. This treatment aims to expand the business networks of participants and increase their opportunities for business collaborations. In the second treatment arm, we enrich the online networking groups with legal support. The goal of the additional legal support is to reduce contracting frictions, potentially increasing business collaborations between entrepreneurs who meet on the platform. The legal support entails weekly video lessons by a local corporate lawyer that discusses the risks of collaborations and ways of mitigating these risks through the use of written agreements and effective communication. Entrepreneurs can also consult the lawyer individually during the four-month intervention period.

The intervention was implemented between February and June of 2021, and we then conducted a post-intervention midline survey between August and October 2021 and a one-year follow-up survey between April to July 2022. Qualitative interviews were conducted in March 2023 to identify mechanisms and a longer-run follow-up survey is planned for April to July 2024.

Networking groups improve firm outcomes

We find that access to online networking groups has significant positive impacts on firm outcomes. First, one year after the intervention, the treatment groups increased business innovation by 25 to 31%, as measured by the likelihood of introducing changes to their businesses, such as new products or new ways of marketing.

Second, we also document an improvement in business practices, driven by a positive effect on marketing and financial planning practices. For example, we find increases in firms’ use of advertisement and special offers, as well as in their likelihood to review financial performance and set sales targets.

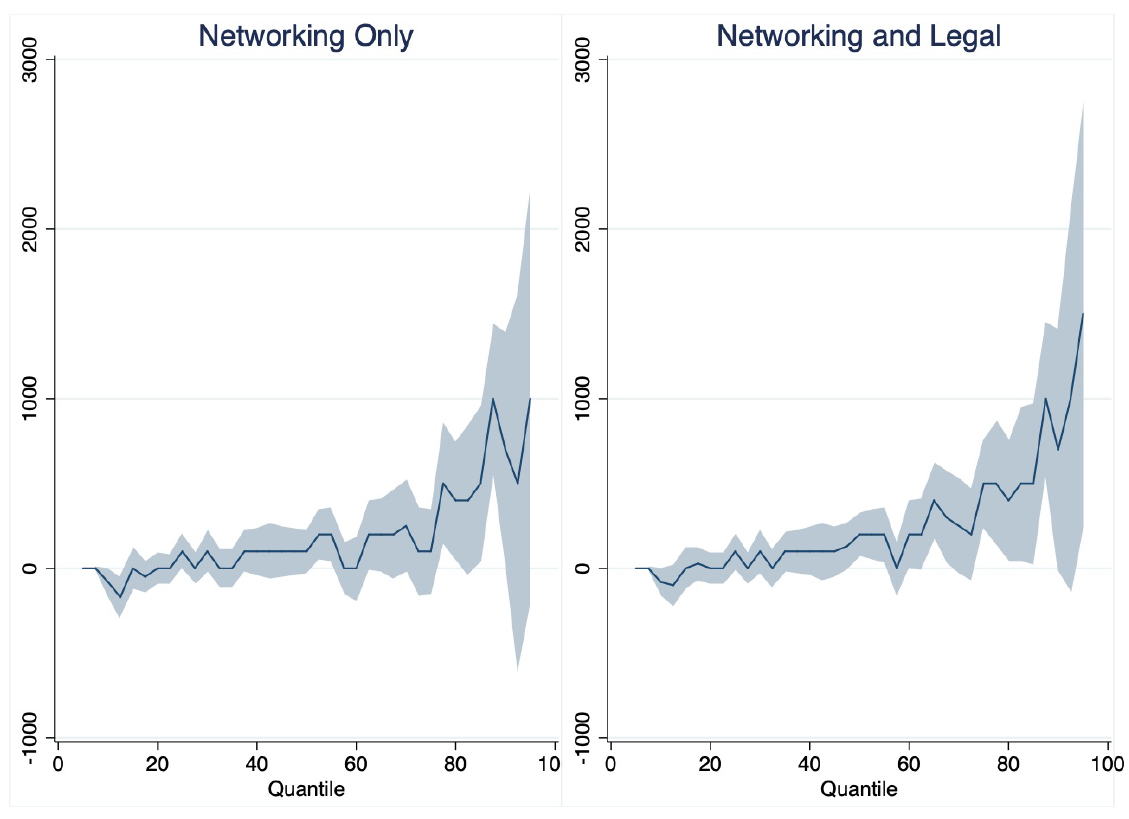

Third, the treatment groups also experience a 21% increase in business profits. Similar to previous work on business training (Dalton et al. 2018), there is a null effect on sales, suggesting that the intervention led to efficiency gains through a reduction in costs and improvements in business practices. Quantile estimates show that the effects are not homogenous across businesses. Instead, a significant increase in profits emerges above the 60th percentile in profits for both treatment groups, suggesting that firms in the upper tail of the distribution benefited more from the intervention. This result is similar to evidence found for microfinance (Breza and Kinnan 2021).

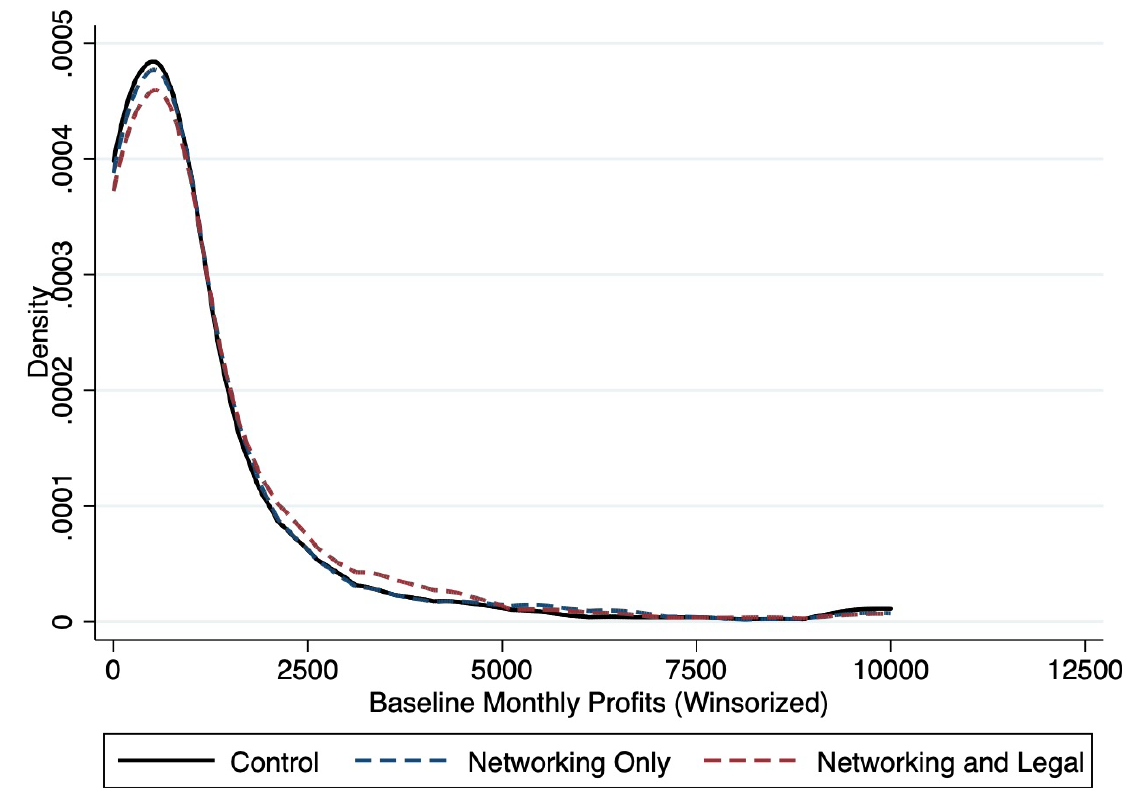

Figure 1: Distribution of monthly profits by treatment status

Figure 2: Quantile effects on monthly profits

The results on business performance are not significantly different between the two treatment arms, suggesting that the reduction in networking constraints drives our results and that legal support does not appear to have an additional influence on business outcomes.

The role of business collaborations and peers

Why did access to online networking groups lead to an improvement in business outcomes? We find that the results cannot be explained by changes in business ambitions, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, get-ahead attitudes, or measures of female empowerment. Instead, we show that the results can be explained by two important channels.

First, we find that the intervention changed the nature of business collaborations. Entrepreneurs in the treatment group reduced collaborations with friends and family, choosing instead to work with business network members. This shift in collaborators comes from a change in beliefs about the quality of potential collaborators, with treated entrepreneurs perceiving a higher return to collaborating with someone external to their friends and family network. Consistent with the change in beliefs, the treatment group also exerted greater search effort and are more likely to contact and meet firms external to their existing friends and family network.

Second, we show that peer effects play a key role in explaining our effects. Female entrepreneurs randomly assigned to WhatsApp groups with more entrepreneurs that are university-educated, have better baseline business practices, and higher baseline sales and profits, are more likely to innovate, improve business practices, and have higher profits themselves. We also find that the businesses of entrepreneurs in groups with a larger share of peers from the same industry are less likely to improve. This suggests that networking with high-quality entrepreneurs with diverse experiences can accelerate firm growth and innovation.

Policy implications

Our study highlights the important role of business relationships in closing the gender gap in business outcomes. The findings suggest several important considerations for interventions:

- Promoting networking opportunities: Our findings show that expanding professional networks for growth-oriented female entrepreneurs can be effective in improving business outcomes such as innovation, business practices, and profits.

- Online, scalable interventions: The intervention in this study was carried out online, showcasing the potential for low-cost, scalable solutions to improve outcomes for female entrepreneurs. Governments and organisations should consider leveraging digital platforms to facilitate networking opportunities, making these resources more accessible to a larger number of entrepreneurs. The fact that such interventions can be carried out remotely can also enable them to reach to women entrepreneurs in rural or remote areas, thus potentially addressing regional disparities in access to business resources.

- Incorporating diversity: The results indicate that a diverse network, especially one that includes high-quality entrepreneurs with different experiences, contributes to business success. Policies and programmes should be developed to foster interfirm relationships and collaborations with a diverse range of entrepreneurs.

More generally, our study opens up exciting avenues for further research on how to best facilitate networking for female entrepreneurs. While our intervention with legal support didn't show significant immediate impacts, the benefits of such support may materialise over a longer time span. Thus, comprehensive and long-term analyses can contribute to a broader understanding of diverse strategies and supports that can help female entrepreneurs succeed.

Editor's note: This work was partly funded by PEDL.

References

Ashraf, N, A Delfino, and E L Glaeser (2019), “Female entrepreneurship and trust in the market.” NBER Working Paper 26366.

Asiedu E, M Lambon-Quayefio, F Truffa, A Wong (2023), “Female Entrepreneurship and Professional Networks” PEDL Working Paper, Available here.

Breza, E and C Kinnan (2021), “Measuring the Equilibrium Impacts of Credit: Evidence from the Indian Microfinance Crisis.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(3): 1447-1497.

Cai, J and A Szeidl (2017), “Interfirm relationships and business performance.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(3): 1229–1282.

Dalton, P, J Ruschenpohler, B Uras, and B Zia (2018), “Learning business practices from peers.” DFID Working Paper.

Kanter, R M (1994), “Collaborative advantage: The art of alliances.” Harvard Business Review.

World Bank Group (2019). Profiting from parity: Unlocking the potential of women’s business in africa. World Bank.