While urbanisation and socioeconomic factors played a role, the global decline in fertility is largely due to successful population control programmes

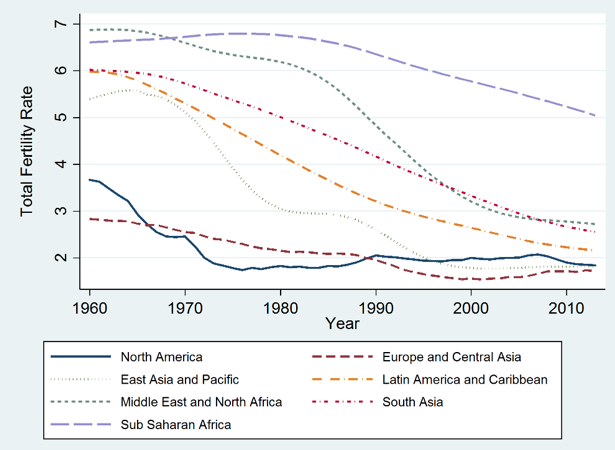

The world’s total fertility rate – defined as the number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children in accordance with current age-specific fertility rates – has fallen dramatically in the past few decades with developing countries (excluding sub-Saharan Africa) reaching fertility rates close to those of developed countries (see Figure 1). Indeed, the world's average total fertility rate declined from over five children per woman in 1960, to 2.5 in 2013. This trend is not driven by just a few countries – in 1960, half the countries in the world had a total fertility rate above 5.8 children per woman. By 2013, the median total fertility rate fell to just 2.2 children per woman, almost equal to the world's estimated replacement fertility rate of 2.25.

Figure 1 Fertility trends across regions

Source: Data from World Development Indicators Database (2015).

Factors behind declining fertility

What explains this decline? A vast literature has sought to explain cross-country differences in fertility with various socioeconomic variables such as income, mortality, urbanisation, and female labour force participation. Our research explores the quantitative role played by these determinants and brings in an additional factor influencing fertility rates – the population programmes started in the 1960s, which, we argue, have accelerated the global decline in fertility rates over the past four decades.

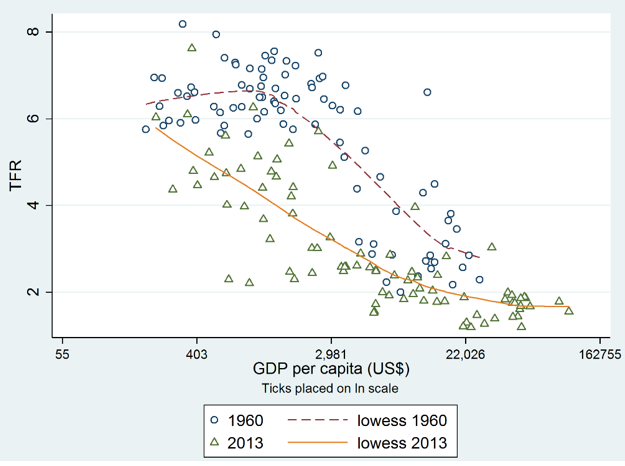

We highlight that the rapid fall in total fertility has taken place in countries at widely different levels of development (measured as GDP per capita). Indeed, though there is a negative relationship between fertility and development across countries, consistent with the Barro-Becker framework (Becker 1960, Barro and Becker 1989), the fertility-development relationship has shifted downwards and become flatter over time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Fertility-income relationship in 1960 and 2013

Source: Data from World Development Indicators Database (2015).

As Figure 2 illustrates, the issue is not just a matter of explaining the decline in global fertility, but also why the fall in fertility rates witnessed by developing countries in recent decades was so very rapid, compared with the rather slow and secular decline in fertility rates experienced by more mature economies. For example, the fertility decline began as early as the mid-1700s in some European countries and only reached replacement levels in the early 20th century (Ansley 1969). Further, it is necessary to explain why countries with markedly different levels of income, urbanisation, education, and other factors are all converging to very similar fertility rates. The worldwide spread of family planning programmes can help to explain these patterns in the fertility data.

The evolution of population programmes

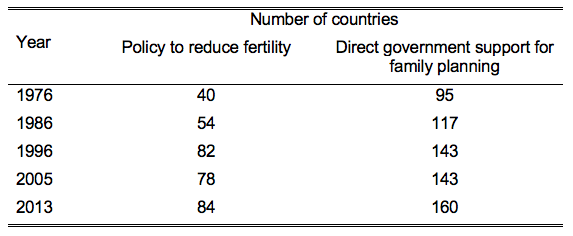

The rapid decline in mortality rates, together with the high fertility rates in developing countries in the post-war period, led to fears of a population explosion. This lent impetus to what effectively became a global family planning programme. The initiative, propelled in its beginnings by intellectual elites in the US, Sweden, and some developing countries (most notably India), mobilised international private foundations as well as national governmental and non-governmental organisations to advocate and enact policies aimed at reducing the total fertility rate (Sinding 2007). By 1976, following the preparation of the World Population Plan of Action at the World Population Conference in Bucharest in 1974, 40 countries, accounting for 58% of the world's population and virtually all of the larger developing countries, had explicit policies to reduce fertility rates. Between 1976 and 2013, the number of countries with direct government support for family planning rose to 160 (see Table 1).

Table 1 Number of countries with a fertility-reduction policy and direct government support for family planning

Source: Data from UN World Population Policies Database (2015).

Collectively, the global family planning programmes provided a policy template for fertility reduction, though there were significant differences in actual implementation, as the policies had to be tailored to the specific context of highly diverse countries. There were two main elements common to all programmes:

- promoting an increase in contraceptive supply and information (preferences and take up rates for different contraceptives varied significantly across countries and over time); and

- creating public campaigns aimed at reversing pro-natalist attitudes and establishing a new small-family norm.

Indeed, the latter appears to have been critical in complementing contraceptive provision, as it became clear that improving the ability to control fertility without increasing the willingness to control it had limited impact. During the 1970s, slogans proliferated in different media – TV, radio, magazines, street posters, brochures, and billboards – all conveying a similar message regarding the benefits of small families.1

While urban areas were easier to serve through the existing transport and communication infrastructure, most countries formed mobile teams to reach residents living in remote rural areas – indeed, some countries, like South Korea, focused their efforts particularly on rural areas. Not surprisingly, then, fertility rates also fell outside urban centres.2 Though religious groups were generally opposed to birth control policies, the family planning programs expanded in Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim countries alike. Remarkably, fertility reduction programs took place under both democratic and autocratic regimes, whether oriented to the political left or right (e.g. Chile under both Allende and Pinochet), and with or without strong government support (in some countries, like Brazil, family planning programmes were initiated and almost exclusively run by non-profit, non-governmental organisations, while in others, like Singapore, China, or India, the government was fully involved).

Role of population policies in falling fertility

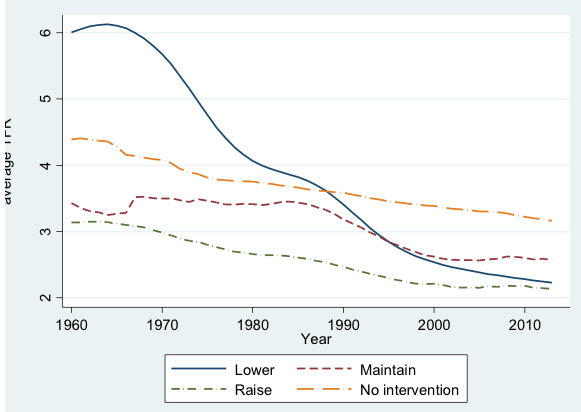

Going to the cross-country data on fertility and population policies, we find further descriptive evidence of the role played by population control policies. Figure 3 shows the striking effect of fertility policy (as observed in 1976) on the mean fertility rate. While fertility has fallen in all regions, even in the group of predominantly European countries that wanted to increase fertility, the countries that had identified the need to reduce fertility by 1976 recorded by far the highest average fertility rates before 1976, but the second-lowest average fertility rates by 2013. The countries where there was no intervention had the second-highest average fertility rates in 1976 and became the highest fertility group by 2013.

Figure 3 Evolution of fertility rates by policy in 1976

Notes: The figure illustrates the evolution of weighted average total fertility rate, with countries grouped by the fertility policy observed in 1976. The policy could be to lower, maintain, or raise fertility; there also could be no intervention.

Different measures of family planning intensity, including per capita funding for family planning and the percentage of women exposed to family planning messages through mass media, show strong positive associations with subsequent reductions in fertility. These associations hold even after controlling for the changes in education, income, infant mortality, and urbanisation that took place during this period. The exercise demonstrates that, while socioeconomic factors play a role, the population control programmes accelerated the global decline in fertility.

Concluding remarks

The absolute convergence to a global fertility rate close to replacement rates will lead to a constant population level, reducing environmental concerns over explosive population growth. To the extent that lower fertility rates are associated with higher levels of capital per capita (through lower capital dilution) and higher investment in human capital, particularly for women (Goldin and Katz 2002), the trends bode well for development and living standards in the poorest regions of the world.3

References

Ansley, J C (1969), “The decline of fertility in Europe from the French Revolution to World War II”, in S Behrman and L Corsa (eds), Fertility and Family Planning: A World View, The University of Michigan Press: 3-24.

Becker, G S (1960), “An economic analysis of fertility”, in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries, Columbia University Press: 209-40.

Barro, R J and G S Becker (1989), “Fertility choice in a model of economic growth”, Econometrica 57(2): 481-501.

De Silva, T and S Tenreyro (2017), “Population policies and fertility convergence”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4): 205-28.

Goldin, C and L F Katz (2002), “The power of the pill: Oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions”, Journal of Political Economy 110(4): 730-770.

Robinson, W C and J A Ross (eds) (2007), The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three decades of population policies and programs, The World Bank.

Sinding, S W (2007), “Overview and perspectives”, In W C Robinson and J A Ross (eds), The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three decades of population policies and programs. The World Bank.

Endnotes

[1] Other measures put in place, although not uniformly in all countries, were increases in the legal age of marriage (e.g. Egypt and Tunisia), tax incentives (e.g. tax exceptions for families of up to three children in Korea), promotion of domestic contraceptive production, establishment of family planning clinics, post-partum follow-up programs, legalisation of abortion, maternity leave and allocation of public apartments and school choice for families of up to two or three children (e.g. Singapore), and so on. Different countries opted for different specific policies, adjusted to the domestic context.

[2] We use demographic and health survey data for 63 developing countries to carry out a straightforward decomposition of the overall fall in fertility into a within-region effect and an urbanization (or between-region) effect. We find that the within-effect accounts for over 85% of the decline in fertility, while urbanisation accounts for the other 15%. Put differently, fertility has declined significantly in both rural and urban areas and only a small fraction (15%) of the decline in fertility can be accounted for by urbanisation.

[3] Insofar as the US experience can be of guidance, the diffusion of contraception, the decline of fertility, and the postponement of childbearing could increase female empowerment in developing countries through higher levels of investment in human capital (Goldin and Katz 2002).