Pregnancy rates fell by almost 7% as a result of the public health information provided on the Zika epidemic by the Brazilian government

Viruses and viral outbreaks have shaped the course of human history. Of course, viral outbreaks differ in many ways, such as the individuals most at risk, the vector of transmission, fatality rates, and their degree of contagion or basic reproduction number.

Despite these differences, nearly all viral outbreaks increase the risks and uncertainty households face, as they emerge without warning and without treatment being available. As such, public health alerts are a vital tool policymakers have in the early stages of epidemics, when behavioural responses of households play a key role in determining the trajectory of viral diffusion and the overall severity of any outbreak.

In a new working paper (Lautharte Junior and Rasul 2020), we study how households responded to public health alerts during a pandemic that was caused by the Zika virus in the Americas in 2015-16. Using tens of millions of administrative records from vital statistics and hospitals, we study how households – in particular pregnant women, who were the group most at risk – responded to this health emergency in Brazil.

Public health alerts during the Zika epidemic

The Zika pandemic was the first ever known association between a flavivirus, carried by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, and congenital disease, representing a “new chapter in the history of medicine” (Brito 2015). The congenital disease most closely linked to the Zika virus in the 2015 epidemic was microcephaly, a neurological disorder amongst newborns in which the occipitofrontal head circumference is smaller than 98% of all newborns.

The timeline of the epidemic is as follows:

- In March 2015, the WHO received notification from the Brazilian government regarding an illness transmitted by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, but not detected by standard tests.

- Until early November 2015, while it was known that Zika was present in Brazil, the perception was that it was a ‘dengue-like’ infection, and harmless to newborns.

- However, on 11 November 2015 the Brazilian government issued an alert emphasising an upsurge in microcephaly in the north-east of the country, and establishing the link to Zika. Within a week, a WHO communique had made explicit mention of microcephaly and the potential link to Zika.

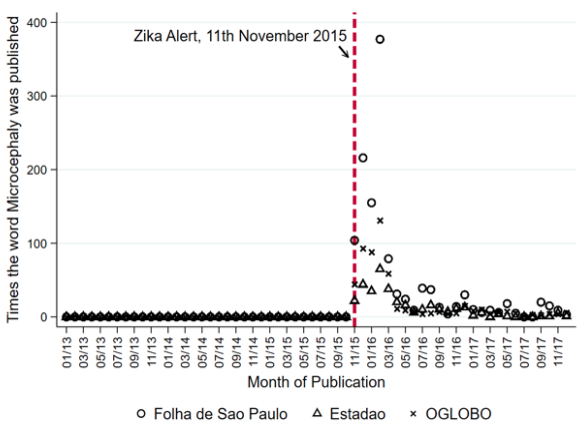

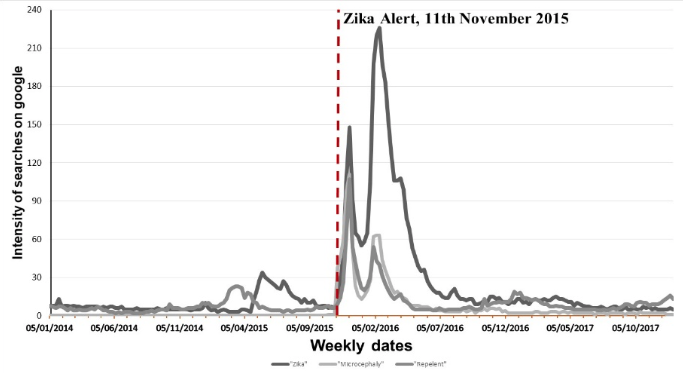

We used millions of administrative records to understand how households responded to the public health alert issued by the Brazilian government in the middle of the epidemic. The public health alert was immediately broadcast on TV media. Figure 1 shows the number of times microcephaly was reported in three leading national newspapers in Brazil. Figure 2 shows the time series of Google searches for Zika, microcephaly (in Portuguese), or repellent.

Figure 1 Mentions of microcephaly in three leading newspapers

Figure 2 Google searches for Zika, microcephaly and repellent

In the context of Zika, where transmission is mainly through mosquitoes, the health alert was designed to influence the behaviour of those at risk, namely, pregnant mothers.

A significant fall in conception

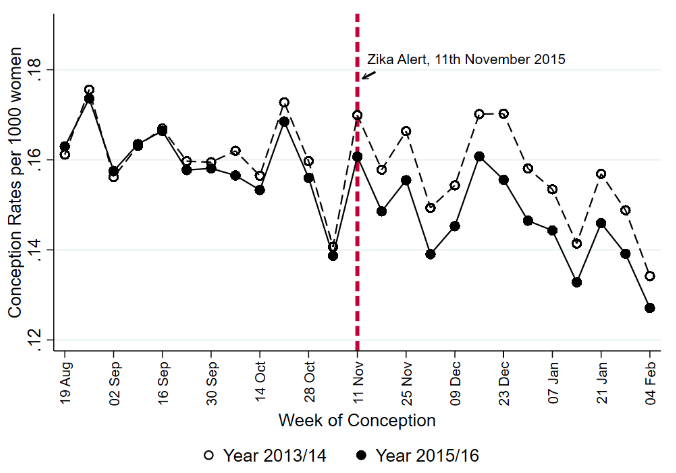

Households in Brazil did indeed dramatically change their behaviour after the public health alert. In particular, women were far less likely to become pregnant: conception rates fell by almost 7% as a result of the public health information provided on Zika, corresponding to around 18,000 fewer children being conceived throughout Brazil in each month after the alert.

As Figure 3 shows, the response was triggered almost immediately. Conception rates started to fall within a week of the health alert, and it took close to a year before they returned to pre-epidemic levels. This suggests that in the midst of a pandemic, at-risk individuals do respond quickly to public health alerts. Moreover, it further suggests that the behavioural change can last much longer than the period of the crisis itself, with a slow convergence back to pre-pandemic norms.

Figure 3 Conception rates, by week

Variation in household responses

Not all households in Brazil were equally responsive to the public health alert on Zika. The largest falls in conception rates occurred amongst older and higher socioeconomic status (SES) women. Does this mean that younger and lower SES women were not receiving the same information, or were not responsive to it?

To explore this aspect further, we estimated the likelihood of a child being born with microcephaly amongst different groups of women. Pre-alert, we see differences in microcephaly risk, with higher SES mothers having lower risks. However, these risks equalise across all mothers, including between high and low SES mothers that became pregnant after the public health alert. This suggests that all pregnant women, irrespective of their age or SES, were able to take precautions during pregnancy to avoid mosquito bites and the accompanying risk of microcephaly. In other words, all women responded to public health information, just in different ways.

The cost of delaying pregnancy might have been especially high for lower SES women. In the Brazilian context, this might be because of the difficulty of obtaining access to family planning facilities. However, the costs of avoiding mosquito bites during pregnancy are relatively low, and can be borne by all through simple preventative measures such as using repellents or wearing long-sleeved clothing.

Internal collaboration is crucial

Finally, our work in Brazil highlights how the ability to access and analyse real-time administrative data can provide leading indicators that help spot viral outbreaks well before they become officially recognised. For example, vital statistics records from Brazil show that the incidence of microcephaly started to rise some months before the public health alert was issued in Brazil, or by the WHO. At least amongst countries with such administrative data infrastructure, new collaborative work between data scientists, epidemiologists, and social scientists is needed to use this real-time data to combat emerging viral outbreaks.

Editors’ note: A version of this article appeared in the IGC blog.

References

Brito, C (2015), “Zika Virus: A New Chapter in the History of Medicine”, Acta Medica Potuguesa 28(6): 679-680.

Lautharte Junior, I and I Rasul (2020), “The Anatomy of a Public Health Crisis: Household Responses Over the Course of the Zika Epidemic in Brazil”.