Adding communication skills training to health classes for mothers in Uganda increased women’s voice in household decisions but not sufficiently to generate transformative impacts on most child health outcomes

In 2019, more than five million children did not live to see their fifth birthday (IGME 2020), and more than 130 million children under the age of five suffered from stunting in low- and middle-income countries (UNICEF 2020). Early-life investments in health and nutrition play a key role in lowering these numbers (Bhutta et al. 2014, Alderman and Fernald 2017).

Existing studies cast light on a telling gender divide: additional resources in the hands of women are more likely to be steered towards improving children’s health and family nutrition (Thomas 1990, 1997, Duflo 2003, Qian 2008, Armand et al. 2020, Dizon-Ross and Jayachandran 2023). This pattern aligns with the rationale behind numerous social programmes that target women as beneficiaries (Fiszbein et al. 2009).

However, targeting transfer payments to women may not always be feasible (Bourgault and O’Donnell 2020), or desirable, for example because of concerns about intra-household disputes or violence. In a recent study, we use a different approach to increase women’s voice in the household regarding child health and nutrition (Björkman Nyqvist, Jayachandran and Zipfel 2023). We explore whether enhancing women’s communication skills can strengthen their influence over child health and nutrition investments through the channel of assertive dialogue with their husbands.

Spousal communication training in Uganda

We leverage an experiment that randomised access to three different interventions across 412 villages in four rural districts of southwest Uganda. Two treatment arms consisted of offering health classes to parents, providing them with information on how to improve children’s health and well-being. In one set of villages, these classes were offered to fathers exclusively, and in another, only to mothers. In the third treatment arm, women were trained in a curriculum on assertive communication in addition to the health curriculum.

The experiment was designed to test two distinct hypotheses. The first is that, because men hold most of the power in the household, increasing their knowledge about child health might be a more effective path to improving child health and nutrition than focusing on mothers. Earlier work by Björkman Nyqvist and Jayachandran (2017) refutes this hypothesis: targeting health classes to mothers improved adoption of health-promoting behaviours by the household more than when the same training was provided to fathers. The second hypothesis, which is the basis of this paper, is that strengthening women’s influence in household decisions could yield tangible benefits for child health and nutrition. To test whether communication skills are one way of achieving this, we compare the impacts of the communication-plus-health-skills intervention for women to those of the women’s health skills intervention alone.

Our analysis unveils five main insights

First, women assigned to the communication training reported an array of positive shifts within their relationships. Enhanced communication with their partners, a reduction in conflicts, and an increase in shared financial decision-making were notable outcomes. Women were also more likely to make decisions about the family’s health and expenses jointly with their husbands. These shifts were perceived from the perspective of women themselves, with men perceiving more modest changes along most dimensions.

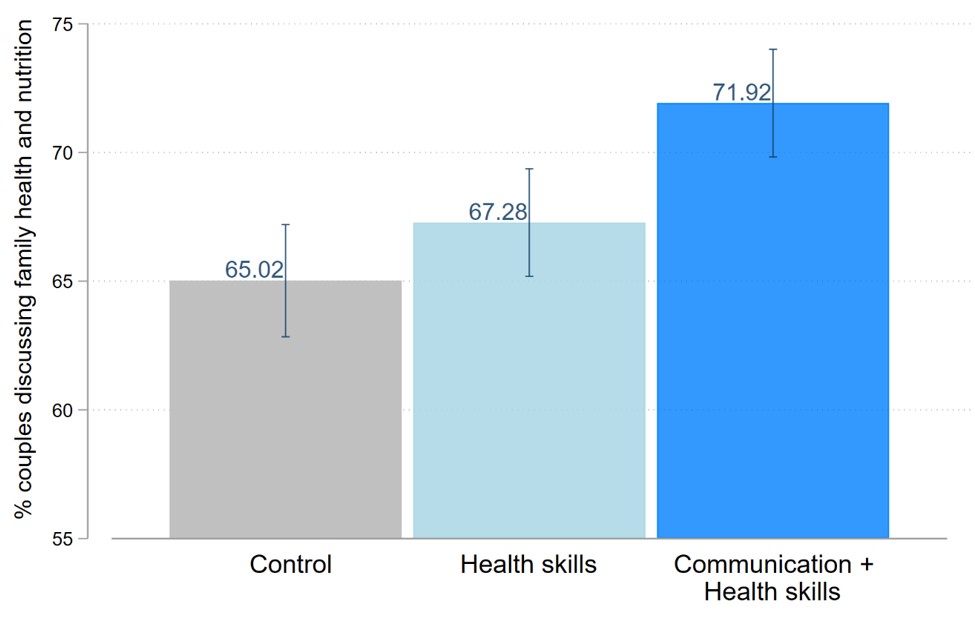

Second, women who underwent the combined training were more likely to discuss targeted health topics and household budgeting with their husbands. For instance, Figure 1 shows that the fraction of couples in which women report frequently discussing the family’s health and nutrition with their husbands is 72% in the communication-plus-health-skills group, compared to 65% in the control group and 67% in the health-skills-only group. Here, a surprising finding is that this increase in spousal discussion did not affect husbands’ knowledge about child health needs, suggesting that either women did not share their new knowledge in these discussions or that men did not retain the information passed on by their wives.

Figure 1: Spousal discussion of family health and nutrition

Notes: Raw means and 90% confidence intervals of the share of households from each group in which women report discussing their family’s health and nutrition “very often” with their husbands. Number of households: 1,379 in the Control group; 1,435 in the Health skills group; 1,330 in the Health + Communication skills group.

Third, we do not detect substantial differences in overall health behaviour adoption between the combined training group and those who solely underwent health education. The share of households implementing recommended health behaviours around newborn and maternal health was significantly higher in the women’s health curriculum arm than in the control group, but the addition of communication training did not improve these outcomes further.

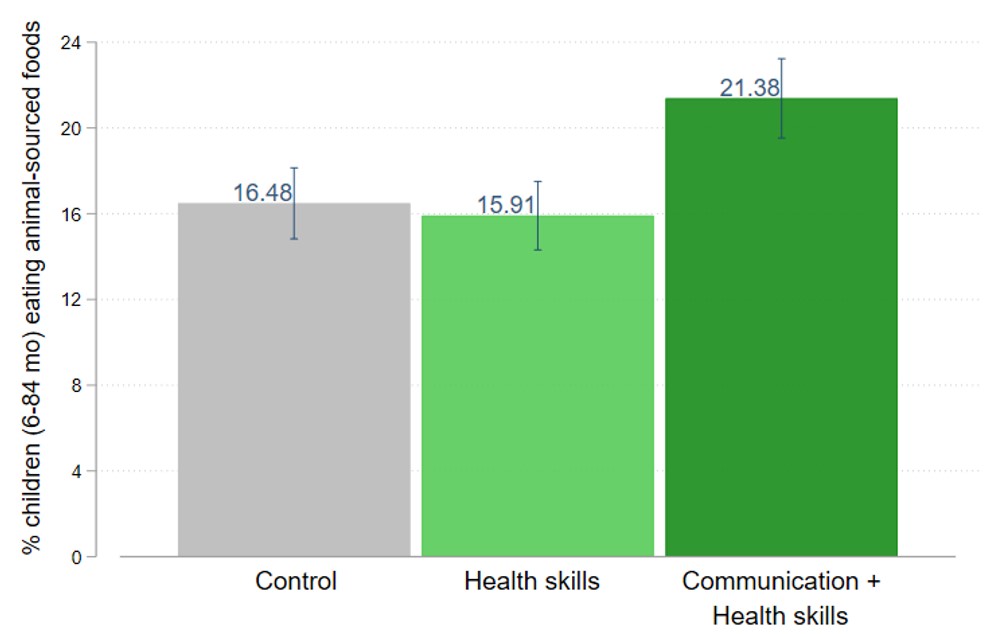

Fourth, while women’s and children’s consumption of starchy foods, fruit, and vegetables increased by similar proportions with or without communications training, only households in the communication-plus-health-skills arm increased their intake of animal-sourced foods (Figure 2). This inclination towards dietary change was mirrored in households’ spending patterns: we observe a significant increase in expenditure on meat and fish in the communication-plus-health-skills group compared to the control group but find no such shift in the other intervention arms. This suggests that women may have applied their newly acquired communication skills to shift household spending towards these foods.

The study's fifth finding centred on child health outcomes. While we do not detect significant shifts in child measurements (weight-for-age or height-for-age), an encouraging improvement in the birthweight of newborns was noted among women who had received communication training, an effect which might stem from better maternal nutrition during pregnancy.

Figure 2: Children's intake of animal-sourced foods at endline.

Notes: Raw means and 90% confidence intervals of the share of households from each group in which children ate at least one type of animal-sourced foods (meat, eggs, fish, or organ meats) in the past 24 hours at endline. Food recall questions were asked to the mother and applied to her two youngest biological children over 6 months and under 84 months (age 7). Number of households (children): 1,376 (1,632) in the Control group; 1,497 (1,803) in the Health skills group; 1,367 (1,613) in the Health + Communication skills group.

Key takeaways from these results

In conclusion, the study offers only nuanced support for its central hypothesis. Our findings indicate that the addition of communication skills training, while effective at increasing spousal communication and women’s satisfaction with their relationship, did not shift women’s voice in household decisions sufficiently to generate transformative impacts on most child health outcomes. Despite this, the increase in consumption of more expensive dietary items like meat and fish suggests the potential for communication training to affect household spending patterns. Additionally, the positive impact on newborn birth weight hints at potential improvements in specific dimensions of child health.

The programme’s overall modest impacts highlight the complexities in shifting the balance of decision-making power within couples through communication training alone. This is in line with other recent research which underscores the intricate nature of communication and information-sharing dynamics between spouses (Conlon et al. 2021, Fehr et al. 2022, Ashraf et al. 2022). Further, the fact that husbands in the communication-plus-health-skills group reported only small improvements in their relationships and marital communication highlights the limitations of the programme’s unilateral approach. A more comprehensive approach that includes communication training for both men and women might hold the key to unlocking more impactful changes. Despite being a costlier, more logistically challenging approach, this might also increase the number of decisions couples make jointly and, thereby, reduce spousal conflict. Exploring whether spousal communication training interventions targeting both men and women can have larger impacts on child health is a promising direction for future research.

References

Alderman, H and L Fernald (2017), “The Nexus Between Nutrition and Early Childhood Development”, Annual Review of Nutrition, 37(1): 447–476.

Armand, A, O Attanasio, P Carneiro, and V Lechene (2020), “The Effect of Gender-Targeted Conditional Cash Transfers on Household Expenditures: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment”, Economic Journal, 130(631): 1875–1897.

Ashraf, N, E Field, A Voena, and R Ziparo (June 2022), “Gendered Spheres of Learning and Household Decision Making over Fertility”, Working Paper.

Bhutta, Z A, J K Das, A Rizvi, M F Gaffey, N Walker, S Horton, P Webb, A Lartey, R E Black, et al. (2014), “Evidence-Based Interventions for Improvement of Maternal and Child Nutrition: What Can Be Done and at What Cost?”, Lancet, 382(9890): 452–477.

Björkman Nyqvist, M and S Jayachandran (2017), “Mothers Care More, but Fathers Decide: Educating Parents about Child Health in Uganda”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 107(5): 496–500.

Björkman Nyqvist, M, S Jayachandran, and C Zipfel (2023), “A Mother’s Voice: Impacts of Spousal Communication Training on Child Health Investments”, NBER Working Paper 30962.

Bourgault, S and M O’Donnell (2020), “Women’s Access to Cash Transfers in Light of COVID-19: The Case of Pakistan”, CGD Note June 2020, Center for Global Development.

Conlon, J J, M Mani, G Rao, M Ridley, and F Schilbach (May 2021), “Learning in the Household”, Working Paper.

Dizon-Ross, R and S Jayachandran (2023), “Detecting Mother-Father Differences in Spending on Children: A New Approach Using Willingness-to-Pay Elicitation”, American Economic Review: Insights, forthcoming.

Duflo, E (2003), “Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old-Age Pensions and Intrahousehold Allocation in South Africa”, World Bank Economic Review, 17(1): 1–25.

Fehr, D, J Mollerstrom, and R Perez-Truglia (2022), “Listen to Her: Gender Differences in Information Diffusion Within the Household”, NBER Working Paper 30513.

Fiszbein, A, N Schady, F H Ferreira, M Grosh, N Keleher, P Olinto, and E Skoufias (2009), “Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty”, World Bank Policy Research Report, Washington, DC, World Bank.

IGME (2020), “Levels Trend in Child Mortality: Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation”.

Qian, N (2008), “Missing Women and the Price of Tea in China: The Effect of Sex-Specific Earnings on Sex Imbalance*”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1251–1285.

Thomas, D (1990), “Intra-Household Resource Allocation: An Inferential Approach”, Journal of Human Resources, 25(4): 635–664.

Thomas, D (1997), “Incomes, Expenditures, and Health Outcomes: Evidence on Intrahousehold Resource Allocation”, Intrahousehold resource allocation in developing countries, pages 142–64.

UNICEF (2020), “Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates”, Geneva, World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.