Providing free access to all modern contraceptive products for three years in local public health centres in rural Burkina Faso had no detectable effect on birth rates, suggesting that fertility levels are in line with how many children families want to have.

Fertility in Africa

Fertility remains high in Sub-Saharan African countries. In Burkina Faso, the average woman gives birth to 4.8 children, over twice the world average. A popular view is that some of these pregnancies are unintended and could be prevented if women had access to affordable and reliable contraception. This view is widely held in policy circles and has shaped government and donor priorities in recent decades. Over 90% of Sub-Saharan African countries have laws or regulations that guarantee access to contraceptive services, and around 3 billion dollars are spent annually in low- and middle-income countries to support contraception access (United Nations 2021, FP2030 2021). Two types of arguments are given in support of these policies. Some see access to contraception as a basic human right that must be guaranteed everywhere (Senderowicz and Valley 2023). Others see access to contraception as a tool to reduce fertility rates and promote economic growth (Canning and Schultz 2012).

However, it is not clear that limited access to contraception is actually driving high fertility. In high fertility contexts, are couples willing but unable to control births (Bongaarts 1990), or are they able but unwilling (Pritchett 1994)? Survey data suggests improving access to contraception could have a large impact on fertility: 20 to 40% of women in low-income countries have an “unmet need for contraception”—i.e. they report not wanting to become pregnant in the next two years and they are not using contraception (UNFPA 2016). But empirical studies have produced mixed results on whether providing contraception in fact lowers fertility.

Previous family planning programmes have had limited effects on fertility

Miller and Barbiaz (2016) reviewed studies estimating the effect of family planning programmes on fertility. Unlike the famous Matlab program in Bangladesh, which substantially lowered lifetime fertility, most other programmes had weaker impacts. These programs typically bundle free contraception with marketing, counseling or other services. Korachais et al. (2016) and Bellows et al. (2016) review the experimental work on subsidising access to contraception alone. They find mixed results on contraceptive use. Surprisingly, few studies examine fertility. Notable exceptions are Desai and Tarozzi (2016) who provided contraception on credit for three years in Ethiopia, and Ashraf et al. (2013) who subsidised injectables and implants for one month and followed women for 9-13 months in Lusaka, Zambia. Neither study found significant effects on fertility.

Our intervention: Improving access to contraceptive products in Burkina Faso

We conducted a large, randomised experiment to study whether removing all financial constraints to access to all contraceptive products for a substantial period of time has an effect on birth rates in rural settings, where 75% of the population lives (Dupas et al. 2024). We enrolled 14,545 married women aged 17 to 35 in rural Burkina Faso. During the baseline survey in 2018, a random subset received vouchers for free contraceptives that could be redeemed in local public health centres, by far the main provider of contraceptives in the country. The intervention was implemented in partnership with the Ministry of Health to ensure that the centres did not need to advance money and did not stock out. Vouchers covered the cost of all contraceptive products and services, including consultation for side effects or removal of an implant. The vouchers were valid for 3 years. Three years later, in 2021, we conducted an endline survey to measure contraceptive use, pregnancies and births.

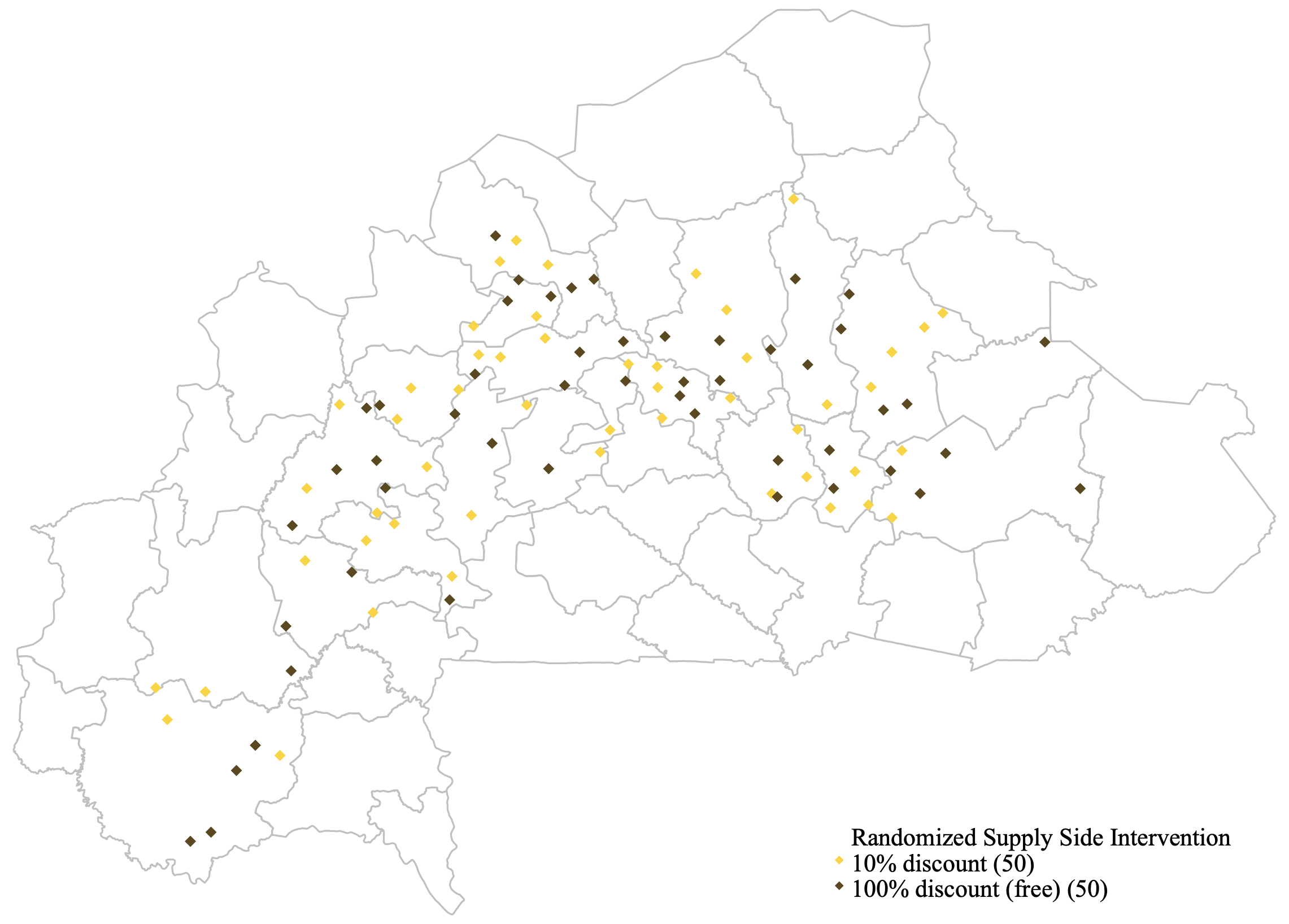

The randomisation was clustered at the health centre level: starting with 100 health centers covering half of the provinces of Burkina Faso, we allocated 50 to treatment and 50 to control. For each health center, we sampled 5 villages in their catchment area, and for each village, we sampled approximately 30 couples. Our final sample, shown in Figure 1, is representative of a large share of the population.

Figure 1: The sample in Burkina Faso

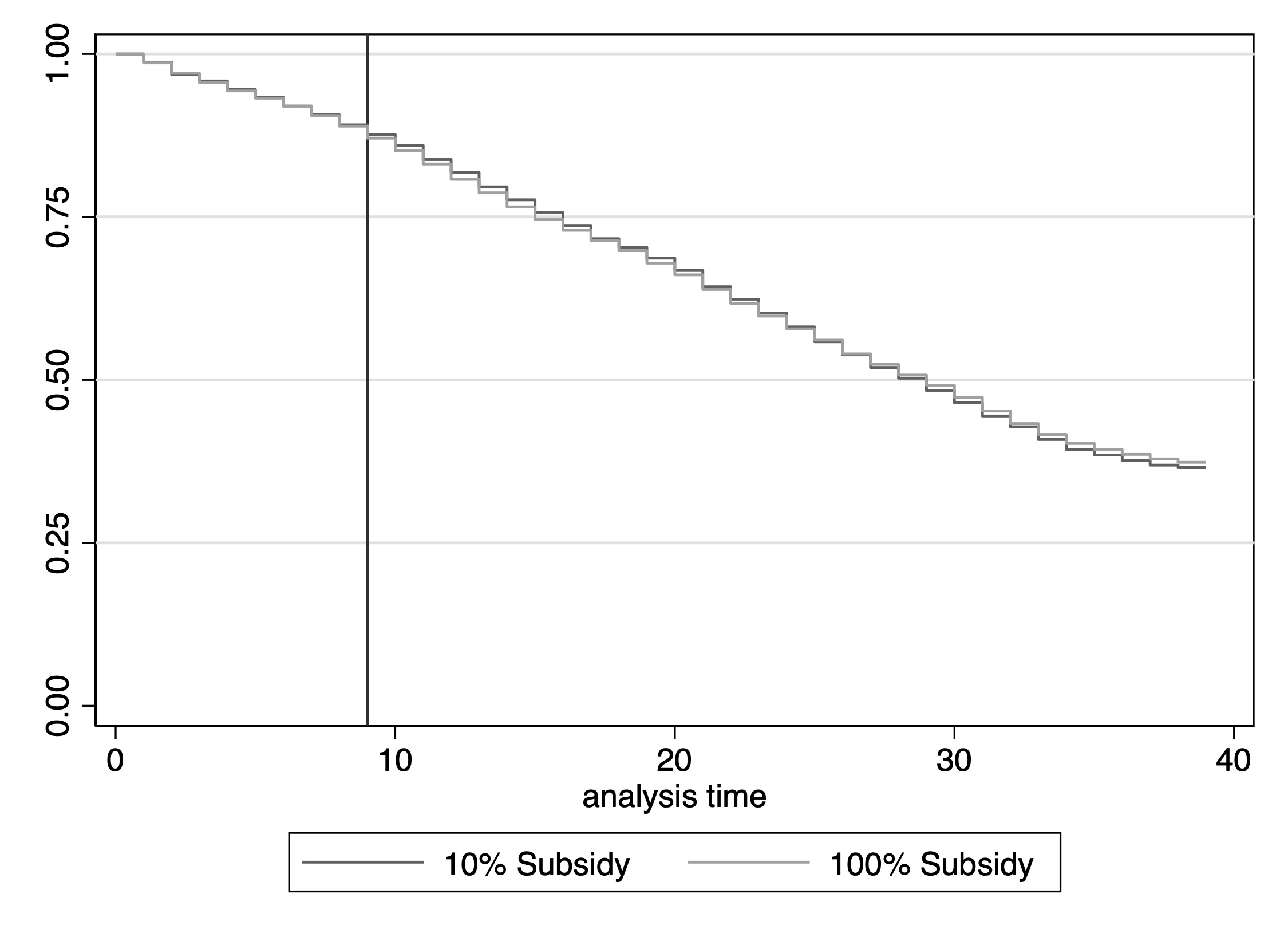

Free contraception has no detectable effect on fertility

We find that free contraception had no detectable effect on fertility, as shown in Figure 2. The x-axis shows time since the baseline survey, in months; the y-axis shows the fraction of women who have not given birth to another child, by treatment status. At baseline (t=0), this fraction is 100% by construction: no one has given birth during our study period yet. Before the first nine months (shown in the vertical line), we see that, as expected, there is no difference between the 10% subsidy group and the 100% subsidy group – a sign that the groups are balanced pre-treatment. If the vouchers had an effect on fertility, we would expect to see a divergence after 9 months. This is not the case: the two curves lie on top of each other, until the end of the period. Three years after the vouchers were given, only 38% of women had not given birth (62% had a child) and this fraction is the same in the treatment and control groups.

Figure 2: The impact of free contraception on fertility

This null result is precise. We can rule out declines larger than 4 percentage points (6.5 percent) in the likelihood of giving birth over the three-year period. We also find small and statistically insignificant effects on contraceptive use. The subsidy did not induce new users to take-up contraception - it simply paid for women who were already using it.

Our large sample size allows us to investigate heterogeneity in many dimensions. The null result holds even for groups expected to be more price-sensitive, including women who satisfy the “unmet need for contraception” definition at baseline, women who did not want another child over the next two years and/or whose husbands did want another child over the next two years, and women who said they could not afford modern contraception. We also find no effect on fertility when we zero in on those who face few non-price barriers to contraception, e.g. those who live close to the health clinic, or who believe modern contraception is safe.

Does fertility decline when other barriers to contraceptive use are simultaneously addressed?

There are many non-financial barriers to modern contraceptive use, including (unfounded) fear of infertility (Bau et al. 2024, Glennerster et al. 2021), male misperception of female mortality risks (Ashraf et al. 2022) and disagreement within couples (Ashraf et al. 2014). Our study design cross-randomised ‘demand-side’ interventions to allow us to investigate two other frictions thought to be important determinants of fertility preferences: perceived social norms (Munshi and Myaux 2006) and child mortality (Notestein 1953, Preston 1978). Indeed, in our baseline, respondents underestimate the social acceptability of birth control and overestimate child mortality. To test whether free access to contraception matters in favourable social and health environments, we designed two interventions to provide information on infant mortality and on social perceptions around fertility practices. We find that free contraception did not influence fertility even in combination with these other interventions.

So, what does drive high fertility?

Our results should not be interpreted as a call for defunding family planning programs but rather as a call for further understanding what drives high fertility. Our findings suggest that fertility levels are in line with how many children families want to have. Contrary to the conventional wisdom in policy circles but in line with early contributions by Becker (1991), Easterlin (1975), and Pritchett (1994), fertility levels might primarily be determined by deep economic factors, and these factors have not changed (enough) in Sub-Saharan countries. Consistent with this interpretation, realised fertility is no higher than stated desired fertility in survey data. Another possibility is that information frictions or social norms are preventing desired fertility from declining. Our unsuccessful attempt to address two of the most commonly cited frictions suggests that removing these barriers, if they are indeed major, might be challenging.

References

Ashraf, N, E Field, and J Lee (2014), “Household bargaining and excess fertility: An experimental study in Zambia,” American Economic Review, 104(7): 2210-37.

Ashraf, N, E Field, and J Leight (2013), “Contraceptive access and fertility: The impact of supply-side interventions,” Cambridge: Harvard Business School.

Ashraf, N, E Field, A Voena, and R Ziparo (2022), “Gendered spheres of learning and household decision making over fertility,” https://voxdev.org/topic/health-education/reducing-fertility-sub-saharan-africa

Bau, N, D Henning, C Low, and B M Steinberg (2024), “Family planning, now and later: infertility fear and contraception take-up.”

Becker, G S (1991), A treatise on the family: Enlarged edition, Harvard University Press.

Bellows, B, C Bulaya, S Inambwae, C L Lissner, M Ali, and A Bajracharya (2016), “Family planning vouchers in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review,” Studies in Family Planning, 47(4): 357-370.

Bongaarts, J, W P Mauldin, and J F Philipps (1990), “The demographic impact of family planning programs,” Studies in Family Planning, 21(6): 299-310.

Canning, D, and T P Schultz (2012), “The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning,” The Lancet, 380(9837): 14-20.

Desai, J, and A Tarozzi (2011), “Microcredit, family planning programs, and contraceptive behavior: evidence from a field experiment in Ethiopia,” Demography, 48(2): 749-782.

Dupas, P, S Jayachandran, A Lleras-Muney, and P Rossi, “The negligible effect of free contraception on fertility: Experimental evidence from Burkina Faso,” https://www.nber.org/papers/w32427

Easterlin, R A (1975), “An economic framework for fertility analysis,” Studies in Family Planning, 6(3): 54-63.

FP2030 (2021), Measurement Report 2021.

Glennerster, R, J Murray, and V Pouliquen (2021), “The media or the message? experimental evidence on mass media and modern contraception uptake in Burkina Faso,” CSAE Working Paper, (2021-04), https://voxdev.org/topic/health/mass-media-meets-motherhood-increasing-contraception-uptake-burkina-faso

Korachais, C, E Macouillard, and B Meessen (2016), “How user fees influence contraception in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review,” Studies in Family Planning, 47(4): 341-356.

Miller, G, and K Babiarz (2016), “Family planning program effects: Evidence from microdata,” Population and Development Review, 42: 7-26.

Munshi, K, and J Myaux (2006), “Social norms and the fertility transition,” Journal of Development Economics, 80(1): 1-38.

Notestein, F W (1953), Economic problems of population change, Oxford University Press, London.

Preston, S H (1978), “Introduction,” in The effects of infant and child mortality on fertility, S H Preston (ed), New York Academic Press, New York.

Pritchett, L (1994), “Desired fertility and the impact of population policies,” Population and Development Review, 20: 1-55.

Senderowicz, L, and T Valley (2023), “Fertility has been framed: Why family planning is not a silver bullet for sustainable development,” Studies in Comparative International Development.

UNFPA (2016), Universal Access to Reproductive Health.

United Nations (2021), World Population Policies, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.