New causal evidence shows boosting African women's income and wealth increases fertility, particularly among women without a son, suggesting that this fertility increase is a means to safeguard long-term economic security.

Changes in fertility have important consequences for economic development and public service provision. In poorer regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, many policymakers are concerned that high fertility rates are hampering maternal and child health, living standards and educational attainment.

The role of economic empowerment in fertility decisions

Improving women’s economic status is often seen as a pathway to decreasing fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. This is because as women’s time becomes more valuable in the labour market, the opportunity cost of having children increases (Butz and Ward 1979). Indeed, numerous studies have found that female earnings and fertility are negatively related (Jones and Tertilt 2008, Doepke et al. 2023).

However, another strand of the literature suggests that fertility can increase with greater wealth if the household desires more children and can now afford them (Lindo 2010, Black et al. 2013, Lovenheim and Mumford 2013). Previous work has also shown that women may have more children to ensure economic security in old age, from both a theoretical (e.g., Becker 1960, Hackman and Kramer 2021) and empirical (Rossi and Godard 2022, Lambert and Rossi 2016) perspective. This last channel is particularly important in a context like sub-Saharan Africa for three main reasons. First, pension systems are either weak or non-existent. Second, men typically marry women who are significantly younger, meaning that most women anticipate ending up as widows. Third, customary laws and norms often exclude women from property ownership and inheritance.

This leads us to the question we explore in our new research (Donald, Goldstein, Koroknay-Palicz and Sage 2024): What is the fertility response to development programmes that increase women’s earnings and household wealth in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Pooling RCT data from programmes that increased women’s wealth

To answer this question, we pool data from six experimental evaluations of business training and land titling interventions that were designed to, and succeeded in, increasing women’s income or the value of household assets in Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana, Rwanda and Togo (Ali et al. 2015, Campos et al. 2017, Goldstein et al. 2018, Alibhai et al. 2019, Agyei-Holmes et al. 2020, Bakhtiar et al. 2022). All of these studies use an RCT or quasi-experimental design to form a treatment group and control group, and impact is measured by comparing the treatment to control group post-intervention. Importantly, these interventions did not include any content on women’s agency or rights, focusing solely on business skills and property rights certification. Our analysis examines the impact of these interventions on the number of children women have 12-72 months post-intervention.

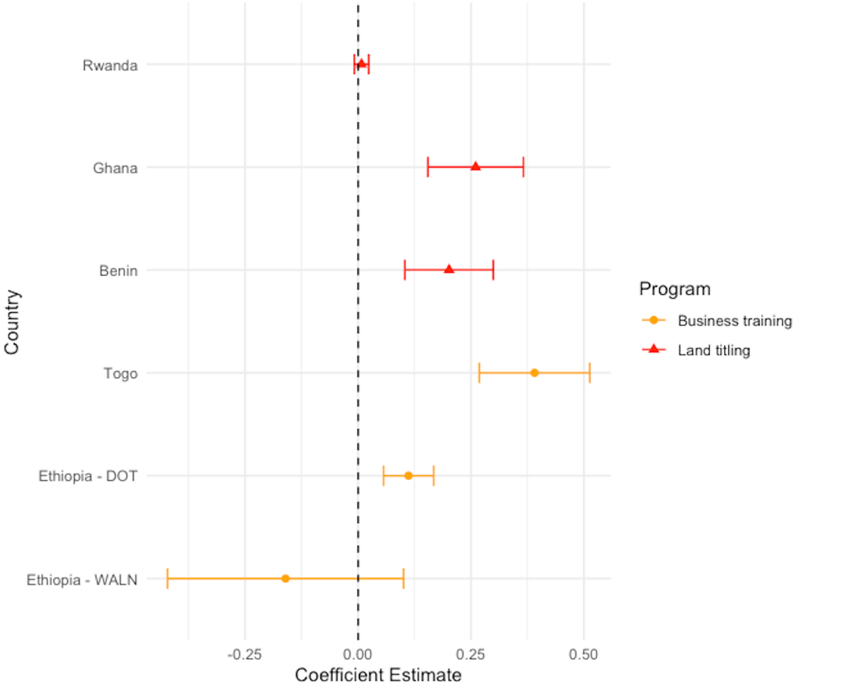

Figure 1: Impact on the number of children at midline

Note: This graph displays the average treatment effect of each intervention on the number of children women have at midline, along with 95% confidence intervals. Source: Donald, Goldstein, Koroknay-Palicz and Sage (2024).

We find significant positive effects on fertility (Figure 1). Women who were randomly assigned to receive a business training intervention were 22% more likely to have a child post-treatment in Ethiopia and twice as likely to have a child under five post-treatment in Togo. Within the land titling interventions, women in treatment villages had 5% more children on average two years after demarcation in Benin, while in Ghana, the increase was 7.5% one year after demarcation. These effects are not statistically different from later effects in subsequent follow-up surveys, indicating that these impacts constitute increases in cumulative fertility—or total number of children—and not merely a shortening of birth spacing. In Rwanda, we find a precise null effect. Interestingly, the land titling intervention in Rwanda was the only one that guaranteed women the right to own and use the land owned by the household in case their husband died—pointing to potential mechanisms.

Why does increased wealth lead to higher fertility rates?

We test several hypotheses to better understand this phenomenon. Women’s increased income does not lead to more children by increasing their say in household matters: there are no impacts on women’s bargaining power in our data, and women’s desired family size is significantly lower than men’s in nearly all countries included in our study. Women’s need for more hands to help out in their business or land also cannot fully explain our pattern of results.

Instead, the hypothesis for which we find the most evidence is that women use childbearing as a strategy to ensure future access to land and income, thereby enhancing their economic security in old age.

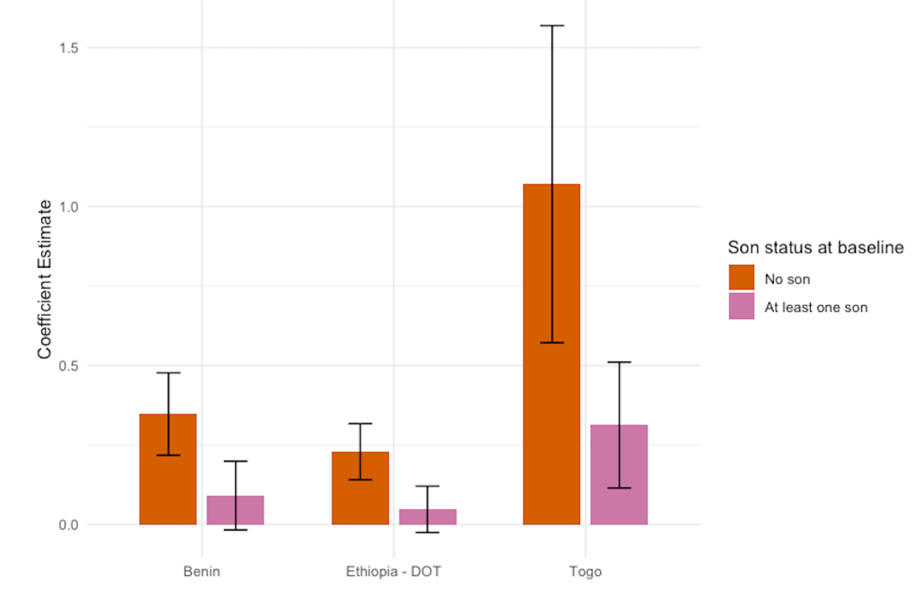

We find that women’s fertility increases the most for women who do not yet have a son (Figure 2). In Togo, where either women or men were randomised to receive the business training, women’s fertility is unchanged if it is their husband’s income that increases, rather than their own. This suggests that the observed increase in fertility does not result from a simple wealth effect at the household level, but depends on women’s own earnings.

Figure 2: Impact on the number of children depending on whether women had a son at baseline

Note: This graph displays treatment effects of the interventions in Benin, Ethiopia (DOT) and Togo on the number of children women have at midline depending on whether they had at least one son at baseline, along with 95% confidence intervals. Source: Donald, Goldstein, Koroknay-Palicz and Sage (2024).

In the land data, we also find that the effect is stronger for women whose husbands have sons from other relationships and could thus be potential rivals for inheritance. In Ghana, the strongest fertility response is among women whose husbands belong to ethnic groups where wives are at greatest risk of dispossession upon their husband’s death. The exception that proves the rule is Rwanda, where the land titling intervention guaranteed equal rights to property for husbands and wives. There, as shown above, we find no positive fertility impacts. Taken together, our results suggest that a key driver of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa is women’s use of childbearing as a strategy to ensure future access to land and income.

What does this all mean?

From a policy perspective, our findings suggest that strengthening women’s property rights is a promising avenue for reducing fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Interventions that secure household-level property rights without ensuring gender equality may inadvertently increase fertility. Ensuring that laws designed to advance gender equality in property ownership and inheritance are both enacted and enforced, along with increasing provisions for widows and the elderly (e.g., through basic income guarantees and pensions), may reduce women’s reliance on their sons and help lower fertility rates.

Note that our results do not speak to the fertility impacts of strengthening the economic prospects of adolescent girls prior to marriage on their future fertility. Indeed, many studies have found this approach to be effective (Jensen 2012, Heath 2017). Our study and findings instead focus on the relationship between income and fertility for adult women, who are already married and already working.

Our study also highlights the value of conducting secondary analyses of RCTs to draw more generalisable conclusions, similarly to Meager (2019) and Vivalt (2015). To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to estimate the causal impact of increased women’s earnings on fertility in a high-fertility, low-income setting. We were only able to do so by re-analysing data from different experiments that had not initially examined fertility. Making impact evaluation data accessible for secondary analysis, including for pooling data from various settings, is crucial for understanding the true impact of development efforts. By doing so, we can optimise the design of future development initiatives and maximise their impact on the communities they serve.

References

Agyei-Holmes, A, N Buehren, M Goldstein, R D Osei, I Osei-Akoto, and C Udry (2020), “The Effects of Land Title Registration on Tenure Security, Investment and the Allocation of Productive Resources”, Global Poverty Research Lab Working Paper.

Alibhai, S, N Buehren, M Frese, M Goldstein, S Papineni, and K Wolf (2019), “Full esteem ahead? Mindset-oriented business training in Ethiopia”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

Ali, D A, K Deininger, M Goldstein, and E La Ferrara (2015), “Empowering women through land tenure regularization: evidence from the impact evaluation of the national program in Rwanda”, Development Research Group Case Study. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/241921467986301910/pdf/97833-BRI-PUBLIC-Box391490B-ADD-SERIES-TITLE-See-73154.pdf (accessed September 9, 2019).

Becker, G S (1960), “An economic analysis of fertility”, in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries, Columbia University Press, 209–240.

Black, D A, N Kolesnikova, S G Sanders, and L J Taylor (2013), “Are children ‘normal’?” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 21–33.

Butz, W P, and M P Ward (1979), “The emergence of countercyclical US fertility”, American Economic Review, 69, 318–328.

Campos, F, M Frese, M Goldstein, L Iacovone, H C Johnson, D McKenzie, and M Mensmann (2017), “Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa”, Science, 357, 1287–1290.

Doepke, M, A Hannusch, F Kindermann, and M Tertilt (2023), “The economics of fertility: A new era”, in Handbook of the Economics of the Family, Elsevier, vol. 1, 151–254.

Donald, A, M Goldstein, T Koroknay-Palicz, and M Sage (2024), “The Fertility Impacts of Development Programs”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper.

Goldstein, M, K Houngbedji, F Kondylis, M O’Sullivan, and H Selod (2018), “Formalization without certification? Experimental evidence on property rights and investment”, Journal of Development Economics, 132, 57–74.

Hackman, J V, and K L Kramer (2021), “Balancing fertility and livelihood diversity in mixed economies”, PLoS One, 16, e0253535.

Heath, R (2017), “Fertility at work: Children and women’s labor market outcomes in urban Ghana”, Journal of Development Economics, 126, 190–214.

Jensen, R (2012), “Do labor market opportunities affect young women’s work and family decisions? Experimental evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127, 753–792.

Jones, L E, and M Tertilt (2008), “Chapter 5: An economic history of fertility in the United States: 1826–1960”, in Frontiers of Family Economics, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 165–230.

Lambert, S, and P Rossi (2016), “Sons as widowhood insurance: Evidence from Senegal”, Journal of Development Economics, 120, 113–127.

Lindo, J M (2010), “Are children really inferior goods?: Evidence from displacement-driven income shocks”, Journal of Human Resources, 45, 301–327.

Lovenheim, M F, and K J Mumford (2013), “Do family wealth shocks affect fertility choices? Evidence from the housing market”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 95, 464–475.

Meager, R (2019), “Understanding the average impact of microcredit expansions: A Bayesian hierarchical analysis of seven randomized experiments”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11, 57–91.

Rossi, P, and M Godard (2022), “The old-age security motive for fertility: Evidence from the extension of social pensions in Namibia”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14, 488–518.

Vivalt, E (2015), “Heterogeneous treatment effects in impact evaluation”, American Economic Review, 105, 467–470.