Subsidies see a greater take up of mechanised latrine desludging than mental accounting nudges for better public health

Poor sanitation choices have large effects on the health of the households making the choices as well as their neighbours. Investing in cleaner, but more expensive, technologies is a challenge for poor households that lack access to financial services. Credit is commonly used to help households spread payments over time. But if the sanitation technology is a service, rather than a durable, financing its purchase through a loan is more difficult because there is no collateral that can be collected in case of non-payment after the service is provided.

We implement a randomised controlled trial (RCT) in Dakar, Senegal, using three alternative financial mechanisms to increase the take up of sanitation services and improve health outcomes in poor households (Lipscomb and Schechter 2018). These include traditional subsidies as well as two mental accounting nudges: earmarked savings accounts and pre-paid deposits. As most of the households in the trial do not have access to banks, we use mobile money to implement all three of the interventions.

The Dakar context: Desludging latrines

Many households in urban areas of developing countries are not connected to the sewage network. These household use latrines instead, which must be periodically emptied. Emptying the latrines is expensive. In Dakar, latrine pits fill up around twice a year. A mechanised ‘desludging’ costs United States (US) $50 and involves hiring a truck to extract the sludge from the latrine pit and take it to a treatment centre. The fee for this can be half of a month’s wages.

Because the cost is so large, many households opt instead for a less expensive manual desludging. A manual desludging involves a person entering the pit, shovelling the sludge into buckets, and then dumping it in the street in front of the house.

Sanitation services and health outcomes: Mental accounting nudges

It has been widely shown that subsidies can increase the take-up of health-improving technologies (Bates et al. 2012). However, subsidy programmes are expensive and difficult to sustain. Mental accounting nudgesare suggested as an easy and inexpensive approach to encourage good sanitation behaviours.

Mental accounting posits that households maintain several mental spending categories and only allow themselves to make a purchase when they have available funds targeted to that category (Thaler 1985). Accordingly, providing households with accounts earmarked for a specific purpose will increase the amount of spending households dedicate to that use.

Mental accounting also hypothesises that households may be more likely to purchase a product if they feel that they have already invested a ‘sunk cost’ (Thaler 1999). In this case, requiring households to pay a deposit to reserve their improved sanitation service could serve as a sunk cost and increase future purchases.

Mobile money: Wari

The RCT was conducted with urban residents in Dakar, whose households’ were not connected to the sewage network (Lipscomb and Schechter 2018). We worked with mobile money provider, Warito implement the treatment mechanisms in a consistent manner.

Wari teams up with gas stations, internet cafes, and local corner stores, providing them with a much wider reach than a traditional bank. Individuals can transfer money by visiting any Wari partner. Although Wari is the primary mobile money provider in Dakar, their focus has been on transfers rather than savings. They did not offer mobile savings accounts before working with us.

The intervention: Subsidies, deposits and savings

We randomly offered households one of two subsidised prices for a mechanised desludgingpurchased through our programme. The average cost of an unsubsidised mechanised desludging is US$50 and the average cost of a manual desludging is US$29. With this in mind, we offered subsidised prices on mechanised desludgings. This meant randomly offering half of the households a price of US$48 and the other half a price of US$34. We also randomly required some households to leave a deposit of US$6, which was also the amount of their payment for participation in the survey, if they wanted to sign up for our programme.

Therefore, our intervention varied:

- subsidy levels,

- pre-paid deposit requirements, and

- access to earmarked savings accounts.

We then randomised households into three different account treatment arms:

- The household had access to an earmarked mobile money account that they could use to save money for sanitation expenses whenever and however much they desired.

- Provided the household with an earmarked mobile money account, but this time the household received monthly bills for 1/6 of the cost of the mechanised desludging.

- The business-as-usual arm, required to deposit the desludging fee as a one-time payment before they received their service.

The randomised households in the sample had one of three options:

- Purchasing a mechanised subsidised desludging through our service programme.

- Purchasing a mechanised desludging on the open market.

- Purchasing a manual desludging on the open market.

While our goal was to encourage households that were going to purchase a manual desludging to switch to more sanitary mechanised desludgings, the subsidies and savings accounts may also have encouraged households that were going to purchase a mechanised desludging anyway to switch to our subsidised service.

The findings: Subsidies improved sanitation but the mental accounting nudges did not

Receiving the larger subsidy increases the likelihood that an individual purchases a subsidised mechanised desludging through our programme by eight percentage points. This translates into a three percentage point increase in the likelihood of purchasing a mechanised desludging overall, since the high subsidy did decrease the likelihood of purchasing a mechanised desludging on the open market by six percentage points. This confirms that subsidies on preventive health products increase their take-up.

The households randomised into the group asked to put down a prepaid deposit were no more likely to purchase a subsidised mechanised desludging than households in the group that was not asked to pay a deposit. Therefore, the mental nudge coming from the deposit requirement had no impact on desludging behaviour.

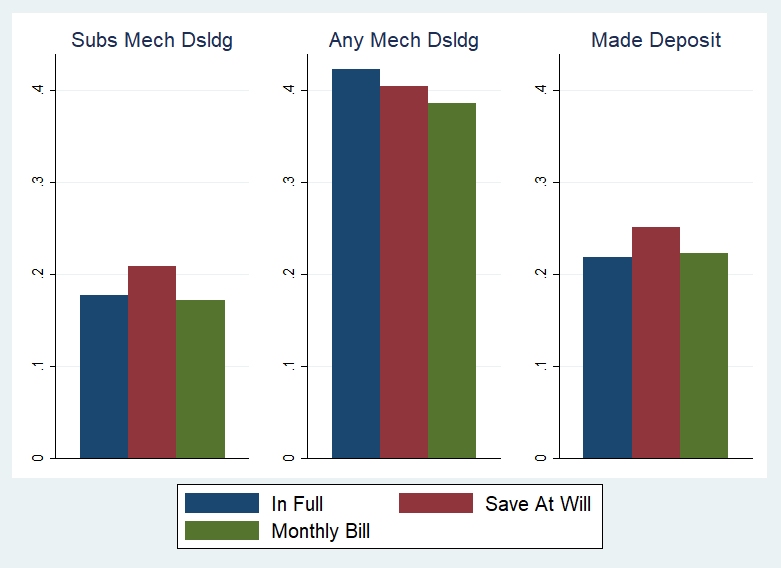

As shown in the figure, households that had access to earmarked mobile money accounts in which they could save at will were most likely to both save in the account over time and purchase the subsidised mechanised desludging service from our programme. The monthly billing treatment had no significant impact on desludging behaviour.

Interestingly, while purchases of the subsidised mechanised desludgings we offered increased by six percentage points in the treatment group with access to earmarked accounts in which they could save at will, this was not matched by an increase in purchases of mechanised desludgings overall. Households in this treatment arm switched from purchasing mechanised desludgings in the open market to purchasing from the programme, however, they did not switch from manual to mechanised.

Figure 1

Conclusion

Mental accounting nudges to save for and purchase a desludging had little overall impact on households’ use of mechanised desludging. Households did, however, enjoy increased access to the fully flexible mobile money savings accounts. They also increased their purchases of desludgings from our project relative to purchases in the market.

Our findings suggest that companies should explore using mobile money savings technologies to market their services and increase their competitiveness. That being said, for governments looking for policies to improve sanitation, mental accounting nudges do not always provide a cheap and easy solution. Tried and true subsidies may be more effective.

References

Bates, M A, Glennerster, R, Gumede, K & Duflo, E (2012). “The price is wrong”, Field Actions Science Reports 6(4).

Lipscomb, M and Schechter, L (2018). “Subsidies versus mental accounting nudges: Harnessing mobile payment systems to improve sanitation”, Journal of Development Economics 135: 235-254.

Thaler, R H (1985). “Mental accounting and consumer choice”, Marketing Science 4(3): 199-214.

Thaler, R H (1999). “Mental accounting matters”, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 12(3): 183-206.