Traffic fatalities linked to informal transit are a disproportionately large cause of death in many low- and middle-income countries, but providing public information can improve safety

Economists broadly agree that markets work poorly when consumers lack reliable information on the quality of products they seek to buy (Akerlof 1970). If consumers cannot judge the quality of a prospective purchase, sellers have no incentive to supply the highest grade. Left unregulated, this generates ‘lemons-markets’.

Preventing the formation of lemons markets

To prevent lemons markets, governments often pass regulations mandating sellers to disclose information to prospective consumers. These can be difficult to enforce in countries that lack the capacity to implement the necessary regulatory framework, as is the case in many low-income countries. The consequences can be extremely harmful; poor product information can compromise the safety of transport vehicles, building supplies, medications, and other live-saving essentials (Bennett and Yin 2018, Bjorkman Nyqvist et al. 2018).

Improving the reliable product information available to consumers is one option for thwarting lemons markets (Bai 2021). With more accurate information on prospective products, consumers can more wisely choose among competing options, and sellers are better motivated to improve quality.

In our study (Lane, Schönholzer and Kelley 2022), we investigate the extent to which consumer information improves lemon markets in Kenya’s informal public transit sector. Although the sector accounts for just 10% of all motor vehicles circulating in the country, it is responsible for a disproportionate share of traffic deaths. Macharia et al. (2009) found this to be as high as 70%. The problem is not an isolated one. Informal transit plays a central role in making traffic fatalities a leading cause of death in many low- and middle-income countries (WHO 2020).

Our paper reveals that the benefit to consumers of having access to reliable information on informal transit options depends on two factors:

- Perceptions: Whether consumers perceive the changing information will affect transit safety and whether transit providers believe that the information will change consumer behaviour. These perceptions depend on the amount of competition that providers face in the market, and the information that both providers and consumers have.

- Costs: Whether the benefits of improving transit quality outweigh the costs to transit companies. These benefits and costs are a function of the cost of improving, the number of competitors, and the quality of services they provide.

Information campaigns are unlikely to work if transit companies do not believe they will convince more customers to take their vehicles, and/or if the changes to improve them are too costly. Conversely if companies believe they have a chance of capturing more customers, and/or quality can be improved at low-cost, they will try to improve the services they supply.

Testing the impact of information campaigns on Lemons Markets

We ran a randomized control trial with more than a thousand passengers at one of Kenya’s busiest bus terminals in three stages:

- Stage 1: We equipped 52 buses across five bus companies operating on a major route with safety tracking devices. We provided their managers access to the safety data, allowing them to monitor their drivers’ safety behaviour and ensuring that they had the capacity to improve the safety of their drivers.

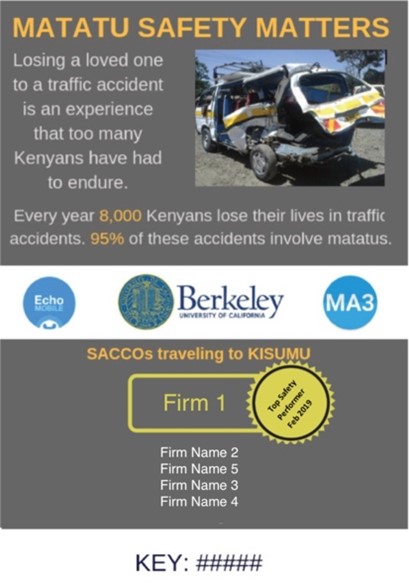

- Stage 2: We rated the top safety performers each month using the GPS data we collected. The top safety performer title was awarded based on measures of speed and sharp breaking. We privately provided the information on the safest companies by distributing pamphlets to a randomly selected group of passengers without informing the bus companies of these pamphlets. We then monitored which transit companies consumers chose. This enabled us to see whether the additional information provided in the pamphlets affected consumers’ choice.

Figure 1: Safety performance award

- Stage 3: In addition to the pamphlets, we erected large signs across the transit station publicizing our tracking efforts. We then monitored consumers’ choice of transit company, and whether transit companies improved their safety performance. If customers believe companies will improve vehicle safety, we should see them switching to the company that was the top safety performer. We also use the data from the GPS trackers to monitor whether the vehicles are driven more safely.

Figure 2: Sign at transit station

Consumer response to the information campaign

First, we find that passengers do not respond to the safety information they receive privately. The behaviour of passengers who received the pamphlet is the same as those who do not. This suggests that passengers do not perceive there to be large differences between bus companies when it comes to safety, and therefore they have no reason to switch based on this margin (relative to other features of the bus that may be driving their choices).

Second, we find that passengers did respond to publicly provided information. Communicating publicly meant that both consumers and transit companies were aware that the other party had access to the information. Consumers who received the pamphlet were now more likely to choose the safe bus relative to those who did not. This suggests that consumers expect some firms to compete on the safety margin and the safest bus is the one that has meaningfully improved the quality they supply relative to others in the market. Taken together this result demonstrates that the effectiveness of consumer information critically depends on whether consumers expect firms to have responded.

Third, we find that additional publicly available safety information improved transit driver safety among the lowest performing companies. On average, we see a 25% drop in speeding alerts, likely contributing to meaningful improvements in road safety. As the effects are concentrated primarily among the two lowest-performing companies, this suggests that consumer information may not affect all companies in the same way.

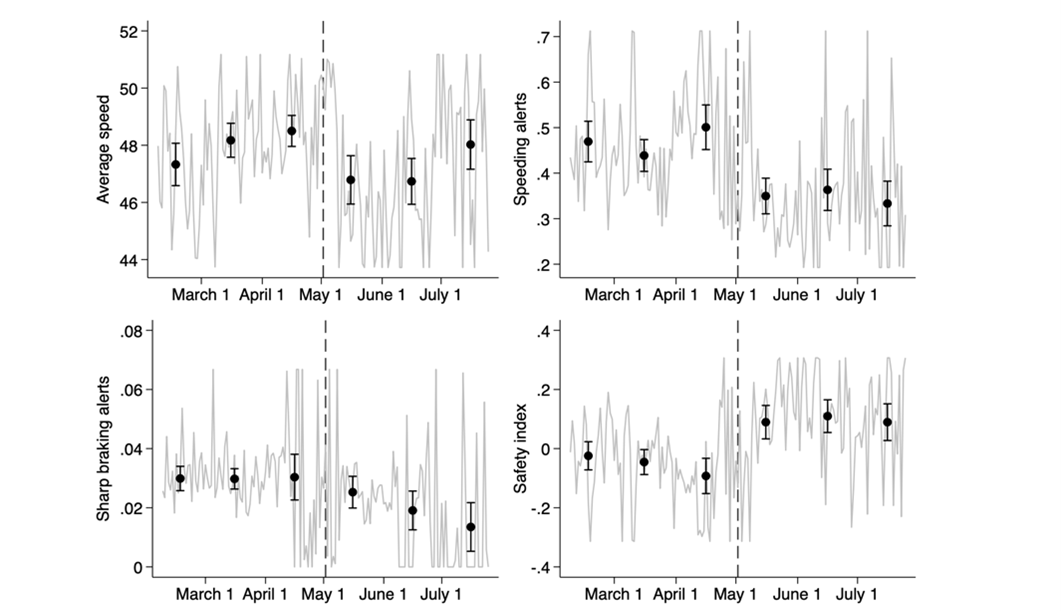

Figure 3: Key outcomes before and after the introduction of the public signal

Notes: Time series of average speed, speeding alerts, sharp braking alerts, and the safety index three months before to three months after the introduction of the public signal. The gray line shows daily averages, whereas the black dots show monthly averages with 90% confidence intervals computed from robust standard errors.

Interpreting the demand and supply changes

We interpret the changes in demand and supply through the lens of a game-theoretic model in which heterogeneous consumers and firms strategically respond to incentives for safety. We show that three types of equilibria are possible: a pooling equilibrium in which no firm provides safety; a separating equilibrium in which only some firms improve their safety performance; and a pooling equilibrium in which all firms supply safer transport. The demand and supply responses to our experiment allow us to distinguish between these equilibria. The evidence suggests that the public information intervention induced a separating equilibrium in which only some of the firms improved their safety performance. In our second contribution, this model provides a foundation for welfare analysis of consumer information in markets with strategic firms. We estimate that the monthly welfare effect of our consumer information was around US$12,000.

What are the implications of these results for optimal policy?

- First, we find that the effect of an information intervention depends crucially on how the market is structured, and whether it is realistic that firms are going to improve the quality of the products/services they supply. This in turn depends on the extent of competition in the market, whether consumers and firms believe the other will react to this new information, and whether firms have the capacity to improve. When considering whether or not to launch information campaigns, policymakers should decide whether they believe consumers and firms will react to the information being shared.

- Second, companies can differ both in their baseline quality levels and their capacity to improve along a certain margin of quality. In settings where baseline differences are large but it is costly for firms to improve how good they can be, a policy that helps companies achieve this quality (say through a subsidy) may be more useful than an information campaign to consumers.

References

Akerlof, G A (1970), “The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3): 488–500.

Bai, J (2021), “Melons as Lemons: Asymmetric Information, Consumer Learning and Seller Reputation”, CID Faculty Working Paper Series 2021.396.

Bennett, D and W Yin (2018), “The Market for High-Quality Medicine: Retail Chain Entry and Drug Quality in India”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(1): 76–90.

Bjorkman Nyqvist, M, J Svensson, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2021), “Can Good Products Drive Out Bad? A Randomized Intervention in the Antimalarial Medicine Market in Uganda”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 20(3) 957–1000.

Lane, G, D Schonholzer and E Kelley (2022), “Information and Strategy in Lemon Markets: Improving Safety in Informal Transit”, Working Paper.

Macharia, W M, E K Njeru, F Muli-Musiime, and V Nantulya (2009), “Severe Road Traffic Injuries in Kenya, Quality of Care and Access,” African Health Sciences, 9(2): 118– 124.

World Health Organisation (2020), “Road Traffic Injuries: Key Facts,” https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries