A radio campaign highlighting the costs of vote buying drew close to 3 million votes away from vote-buying parties

Throughout the developing world, corrupt candidates engage in vote buying and go on to win elections. Vote buying undermines the political representation of voter interests and decreases the supply of pro-poor public services, but there has been limited success in the search for cost-effective strategies to diminish the influence of vote buying in politics.

For policymakers seeking to reduce the influence of vote buying, information campaigns are one potentially promising measure. Experimental studies have measured the impact of campaigns, such as village meetings (Banerjee et al. 2010, Blattman et al. 2020) and door-to-door leaflet distribution (Cruz et al. 2021, Vicente 2014), on voter behaviour. These campaigns have generally been effective, but they are also expensive and labour intensive.

Non-experimental studies have found that radio campaigns can affect voter behaviour (DellaVigna et al. 2014, Ferraz and Finan 2008, Larreguy et al. 2020, Strömberg 2004). Experimentally randomising exposure to a radio campaign to measure effects on voter behaviour is promising and exciting. Radio reaches a wide audience in the developing world and can be scaled up quickly and cheaply. Importantly, radio campaigns are less susceptible to interference by vested interests than on-the-ground campaigns and are therefore safer to implement in regions where violence and intimidation are a concern.

Anti-vote-buying radio campaign in India

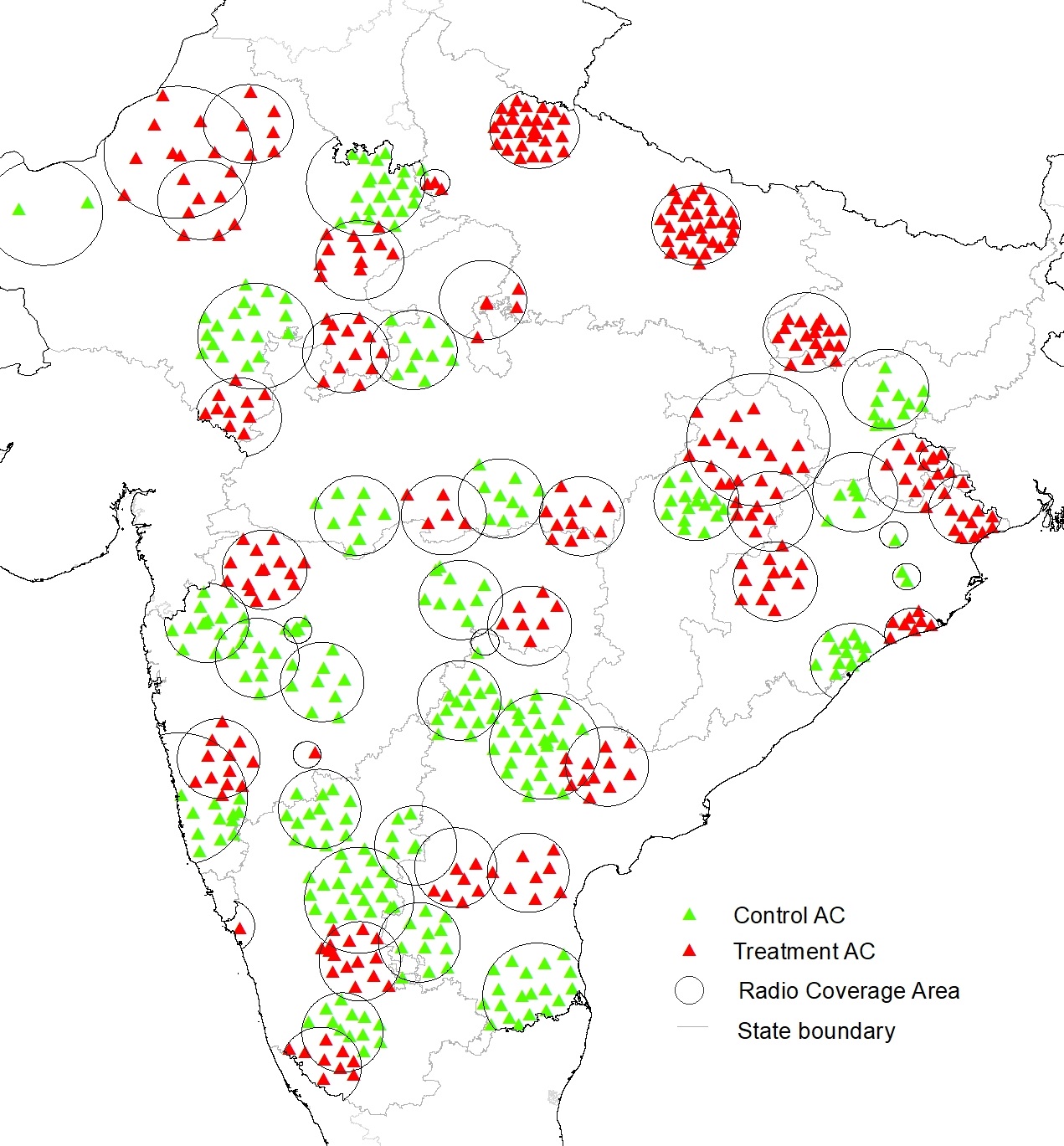

In our research (Schechter and Vasudevan 2023), we evaluated a radio campaign in India that reached millions of voters in the lead up to the 2014 general elections in which voters elected members of parliament (MP) for the 543 parliamentary constituencies (PC) of the country. The campaign was run on All India Radio (AIR), the national public radio broadcaster. Our study included 57 AIR radio stations covering almost 100 million voters. Twenty-nine radio stations were randomly chosen to broadcast the campaign just before citizens cast their votes. Figure 1 depicts all the radio stations in the study along with areas that received the campaign and areas that served as the control group. The total cost of the radio campaign, including producing and airing the ads, was $23,000, or less than $800 per radio station.

Figure 1

The radio campaign consisted of three 60-second ads, each with a dramatised vignette involving a voter who is excited to have received a ‘gift’ from a candidate. The vignette then depicts another voter who explains that candidates who engage in vote buying are likely to steal public money after being elected to recoup their expenditure, at the cost of providing public services like schools and electricity. The ad ends with the first voter deciding not to honour his or her promise to vote for the vote-buying candidate, followed by an appeal by the announcer: ‘‘Teach vote-buying leaders a lesson — use your secret ballot to vote for an honest candidate.’’

The ads were broadcast during the three-day pre-election window when partisan campaigning is prohibited but non-partisan messaging is allowed. The ads were broadcast 48 times on each radio station: 24 prime-time airings and 24 non-prime-time airings; or 18 on the first day, 18 on the second day, and 12 on the third day. This timing balanced the desire to broadcast ads close enough to election day to limit the parties’ ability to respond, with the desire to have a sufficiently long campaign period to ensure high voter exposure to the ads.

How to determine which parties buy votes? Journalist surveys

To measure effects on the vote share of the vote-buying party, one must first know which party is doing the vote buying. Direct observation is usually impossible since vote buying is illegal and is usually hidden. In the past, researchers have used their knowledge of the local situation to make assumptions about which party is the main vote buyer. Blattman et al. (2020) find that an anti-vote-buying campaign in Uganda decreased the incumbent’s vote share, while Vicente (2014) finds that an anti-vote-buying campaign in São Tomé and Príncipe increased the incumbent’s vote share. They argue that in the first case the incumbent is the main vote buyer and in the second case the challenger is the main vote buyer.

We use a different strategy: leveraging the knowledge of local experts. We show that journalist interviews are a relatively simple, safe, reliable, and low-cost way of identifying vote-buying parties and conducted phone interviews with over 400 journalists asking about specific PCs: ‘‘Which party/parties seem to be spending the most money secretly (such as on distribution of liquor, cash, or other gifts)?’’ Specificity and consensus among respondents is high. The journalist reports appear to be unbiased — neither the language or media the journalist works in nor their gender or religion predicts which party they identify as buying votes.

Anti-vote-buying radio campaign decreases votes for candidates who buy votes

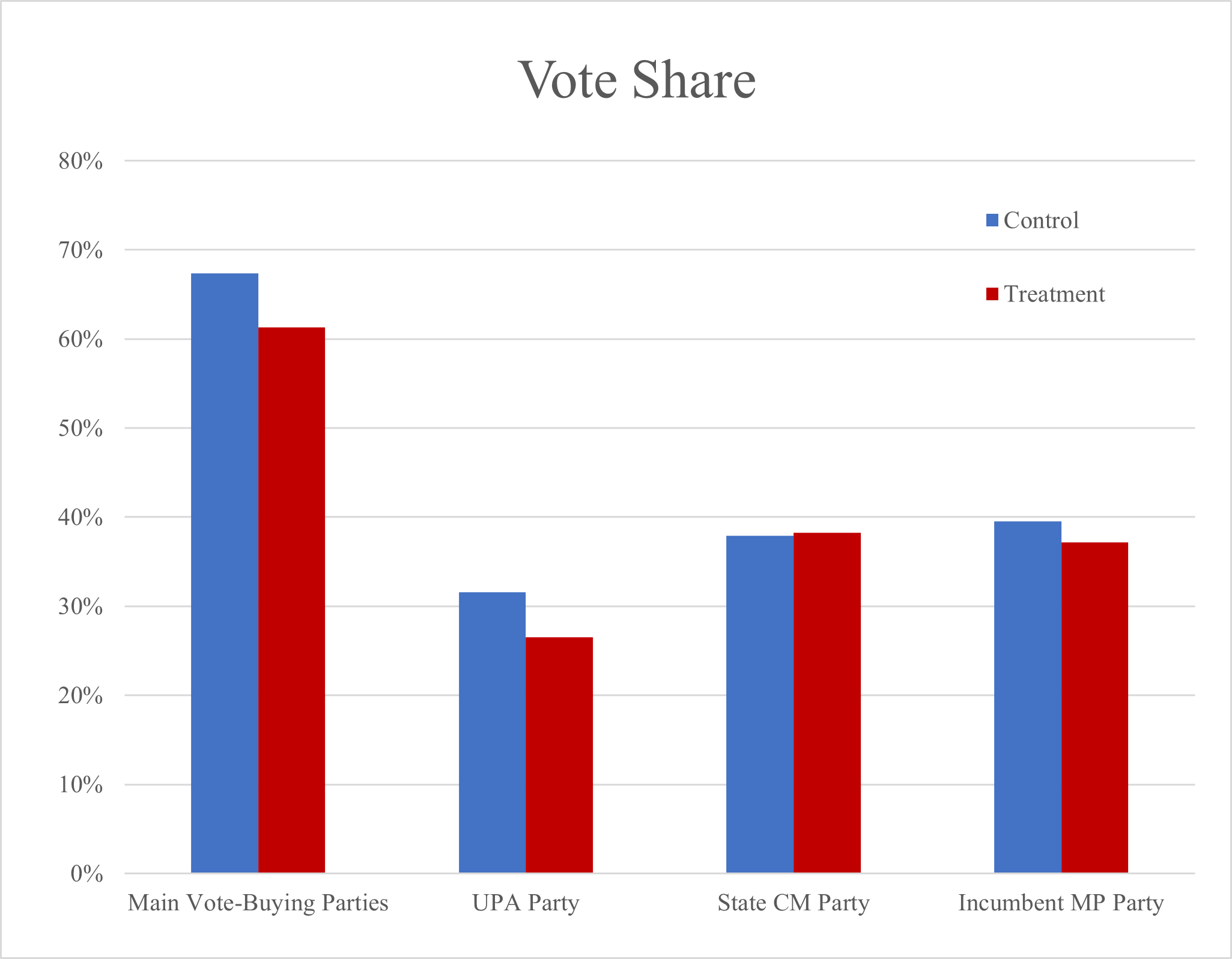

The radio campaign drew close to 3 million votes away from vote-buying parties. The electoral returns data comes from the Election Commission of India (ECI) and is disaggregated by assembly constituencies (AC) within each PC. Results measuring impacts on election outcomes can be found in Figure 2. Electoral support for the main vote-buying parties is high — the mean vote share in the control group ACs is 67%. The radio campaign decreased the vote share of vote-buying parties by 6.1 percentage points.

Figure 2

Impacts on the vote share for candidates from the incumbent party at the national, state, and PC levels is also explored. The radio campaign lowered the vote share of the prime minister’s party alliance (UPA) by approximately 5 percentage points. The campaign did not have significant effects on any of the other vote share outcomes measured. This suggests that the radio campaign changed voter attitudes towards vote-buying parties or those perceived as corrupt. The effect on the voter turnout rate is negative but is negligible compared to the shift in vote share, suggesting that voters responded to the ads by shifting their votes rather than abstaining altogether.

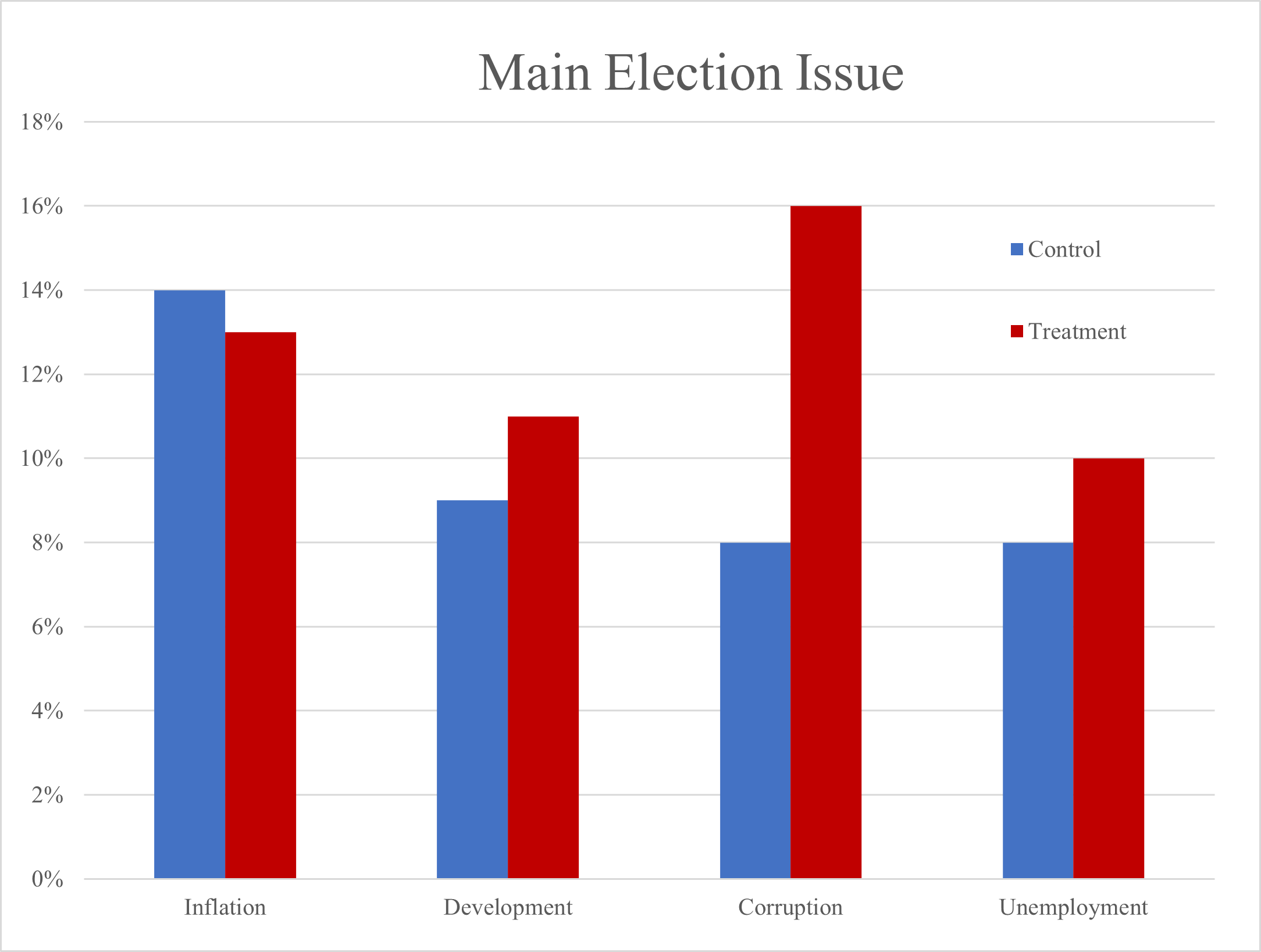

In addition to measuring impacts on election outcomes, we also measure impacts on citizen attitudes. The National Election Study (NES) (2014), a national survey of registered voters, was conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) after voting was completed but before the results were announced. Respondents were asked, “What was the single most important issue for you while voting in this election?” Common answers were inflation, lack of development, corruption, and unemployment and jobs. Results found in Figure 3 show that the campaign increased the salience of government corruption as the most important election issue by 8 percentage points relative to a control mean of 8%. The effects on the perceived importance of other issues are small and not statistically significant. These results suggest that voters may have been influenced by the campaign message linking vote buying to corruption.

Figure 3

Conclusion

Overall, radio campaigns can be a cost-effective alternative to more expensive on-the-ground efforts. Each dollar spent persuaded 130 voters to change their vote, affecting 3 million votes in total, and decreasing the vote share of precisely those parties identified in journalist interviews as engaging in the most vote buying. This study represents the first systematic attempt to evaluate the effects of a large-scale mass media voter education campaign against vote buying.

A pertinent question for the future is whether and how parties respond to media campaigns or to other sources of information. Given the timing of our radio campaign, parties had little time to react. With more time, these campaigns might lead parties to nominate different candidates, make changes to their policy platform, or increase voter monitoring and intimidation.

References

Banerjee, A, D Green, J Green, and R Pande (2010), “Can voters be primed to choose better legislators? Experimental evidence from rural India”, Working Paper.

Blattman, C, H Larreguy, B Marx, and O R Reid (2020), “Eat widely, vote wisely? Lessons from a campaign against vote buying in Uganda”, NBER Working Paper Series 26293.

Cruz, C, P Keefer, and J Labonne (2021), “Buying informed voters: New effects of information on voters and candidates”, Economic Journal 131(635): 1105-1134.

DellaVigna. S, R Enikolopov, V Mironova, M Petrova, and E Zhuravskaya (2014), “Cross-border media and nationalism: Evidence from Serbian radio in Croatia”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6(3): 103-132.

Ferraz, C and F Finan (2008), “Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 123(2): 703-745

Larreguy, H A, J Marshall, J M Snyder Jr. (2020), “Publicizing malfeasance: When the local media structure facilitates electoral accountability in Mexico”, Economic Journal 130(631): 2291-2327

Schechter, L, and S Vasudevan (2023), “Persuading voters to punish corrupt vote-buying candidates: Experimental evidence from a large-scale radio campaign in India”, Journal of Development Economics 160: 102976.

Strömberg D (2004), “Radio’s impact on public spending”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(1): 189-221

Vicente, P C (2014), “Is vote buying effective? Evidence from a field experiment in West Africa”, Economic Journal 124(574): 356-387.