It is only democracies that perform well on the dimensions that the public cares about – economic growth, control of corruption, peace and political stability and public good provision – that build support for democratic institutions

Democracy is in crisis. Freedom House (2022) reports that democracy has been in retreat globally for 16 consecutive years. For example, in 2022, 60 countries experienced declines in their democracy score while only 25 showed improvement, and today the world is less democratic than it has been at any time since 1997. Even more worrying is the trend towards declining support for democracy across the world. In our data, we find that 60% of respondents used to have a positive view of democracy in the mid-1990s, and this number has fallen to 50%.

The future of democracy is intertwined with citizens’ support for it. The idea that democracy needs to be defended to survive is almost as old as democracy itself, going back to ancient Athens (Ober 2015). Benjamin Franklin captured this notion when responding to a question on whether the new country had a republic or a monarchy: “A Republic, if you can keep it.”

But what determines the support for democracy? In a recent study (Acemoglu et al. forthcoming), we show that such support is very closely related to people’s experience of democratic institutions in terms of the things that they care about – economic growth, peace and stability, redistribution and control of corruption. In fact, we find that exposure to democratic institutions that are not successful across these dimensions does not build support for democracy, but exposure to successful democracies strongly does.

This is what the John Betjeman, the one-time poet laureate of the United Kingdom, captured pithily when he wrote: “Our nation stands for democracy and proper drains.” He is not alone. Many politicians, as far back as Franklin Delano Roosevelt understood this. President Joe Biden made the same theme a central tenet of his early policies, arguing: “We have to prove democracy still works—that our government still works and we can deliver for our people. In our first 100 days together, we have acted to restore the people’s faith in our democracy to deliver.”

Exposure to democracy and support for democracy

Using data covering more than 110 countries and exploiting within-country between-age group/cohort variation, we examine whether age groups that have been exposed to longer democratic spells (as well as longer successful democratic spells) express greater support for democracy relative to other age groups in the same country and the same age groups in other countries (who have experienced different timing of democratisations and democratic reversals). To do this, we control for country, year, cohort and age fixed effects (in our more demanding specifications, we add age times subregion or age times country fixed effects).

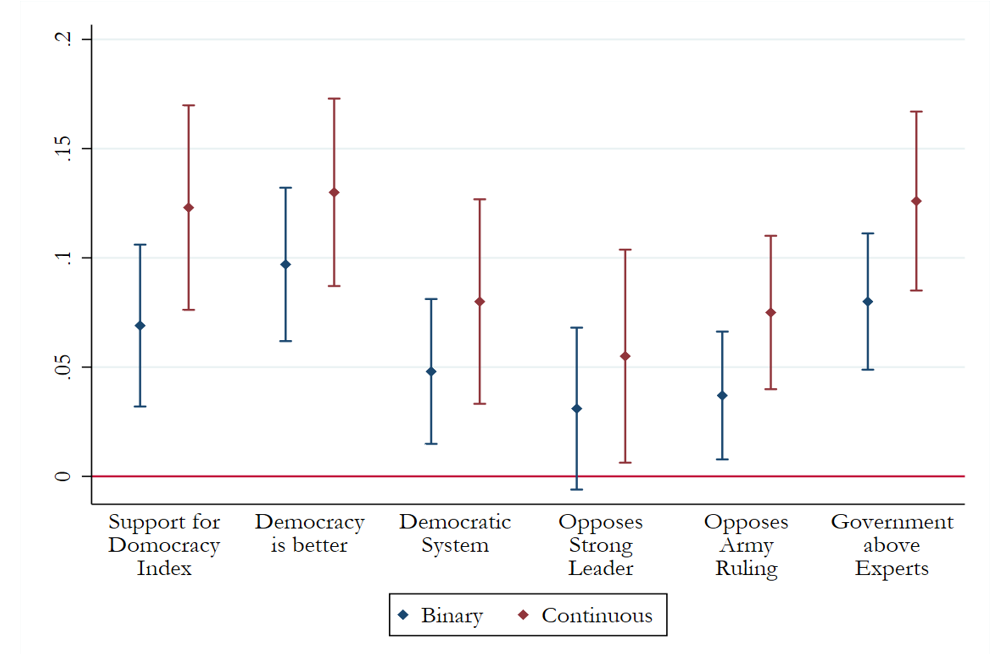

Figure 1 summarises our first key finding, by plotting our main estimates of the effects of exposure to democracy on six measures of the population’s support for democracy. These are derived from answers to five different questions in the World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys. We look separately of the answer to these five questions, related to whether democracy is better than alternatives, whether the democratic system is working, whether the respondent opposes strong (nondemocratic) leaders and army rule, and whether they favour rule by experts. The first variable is an index combining the latter four variables.

In each case, we find that democracy has a stable and statistically significant effect on the relevant metric for support for democracy, and this effect is robust across various specifications. These effects are not just statistically significant and stable, but quantitatively meaningful as well. In terms of exposure to overall democracy, our baseline estimates imply that 20 additional years of exposure to democracy increases support for democracy by about 8% of its standard deviation—more than half of the difference in support for democracy between Hong Kong and mainland China, or between the US and Argentina.

Figure 1: Exposure to democracy and support for democracy

Source: Acemoglu et al. (forthcoming). Notes: Results use the sampling weights. Both the binary and continuous democracy scores (i.e., treatments) are reported. All regressions include a full set of country, year of interview, age, cohort, and wave-survey fixed effects as well as gender dummies and dummies for city size categories. To facilitate comparisons across variables and specifications, we report beta coefficients (computed as changes in standard deviation units of the outcome variable for a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable). Standard errors are computed with two-way clustering at the country and year levels and are robust against heteroscedasticity.

It is successful democracy that matters

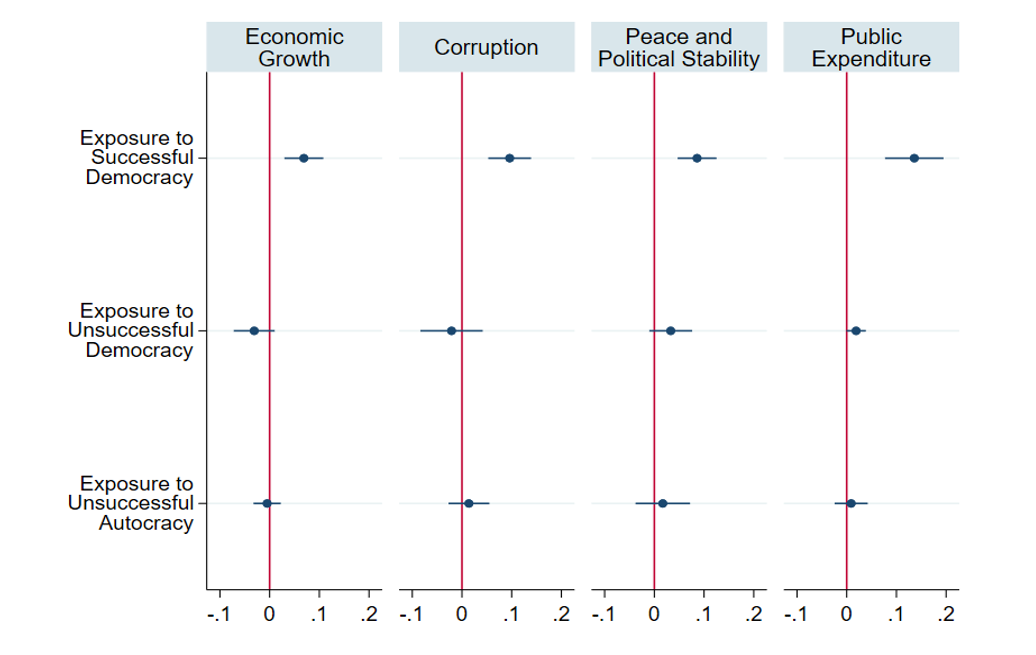

These results, by themselves, might suggest that the mere act of living under democratic system builds support for democratic institutions. This is not true, however. Our main result shows that the patterns depicted in Figure 1 are entirely due to people responding to democratic regimes that perform well according to a number of metrics that they care about – in particular, in terms of democracy delivering economic prosperity, control of corruption, peace and stability and public good provision.

This is documented in Figure 2, which shows that in each case it is exposure to successful democracy that builds support for democratic institutions. In contrast, exposure to unsuccessful democracy does not. Interestingly, exposure to successful or unsuccessful autocracy does not seem to matter much, presumably because autocratic regimes obfuscate their failures and additionally, perhaps, the population is not under any illusion that they will be able to deliver economic prosperity, peace and political stability or control of corruption.

Figure 2: Exposure to successful democracy and support for democracy

Source: Acemoglu et al. (forthcoming). Notes: Results use the sampling weights. Outcome variable is support for democracy index. The figure report OLS coefficient estimates of Exposure to Successful Democracy, Unsuccessful Democracy, and Unsuccessful Autocracy using our baseline sample from Integrated Value Surveys. Successful performance is defined in terms of growth of GDP per capita, low corruption, peace and political stability, and public expenditure, respectively. All regressions use the dichotomous democracy score and include a full set of country, year of interview, age, cohort, and wave-survey fixed effects as well as gender dummies and dummies for city size categories. To facilitate comparisons across variables and specifications, we report beta coefficients (computed as changes in standard deviation units of the outcome variable for a one standard deviation increase in the independent variable). Standard errors are computed with two-way clustering at the country and year levels and are robust against heteroscedasticity.

In all cases, we estimate that the relationship between exposure to democracy and support for democracy is entirely accounted for by individuals with exposure to democratic institutions that have functioned well. For example, 20 more years of exposure to a democratic regime that has been economically successful raises support for democracy by about 8% of its standard deviation (relative to unsuccessful democracies). This is again more than half of the gap between Hong Kong and mainland China, or between the US and Argentina.

Support for democracy matters too

Support for democracy is not a mere sideshow. We also confirm the views of many public intellectuals and politicians from Benjamin Franklin to FDR and Joe Biden that this support is critical for the survival and well-functioning of democratic regimes.

Exploiting the differential response of societies with high and low support for democracy to negative economic shocks, we show that democracies with high public support perform better economically in the face of such shocks and are much less likely to experience coups and other anti-democratic actions relative to democracies with low public support. Reassuringly, we do not find a similar divide between autocracies where the population is or is not supportive of democratic institutions.

Conclusion

Our study provides strong support for the view that democracies breed their own support, but do not do so automatically. It is only democracies that perform well on the dimensions that the public cares about – economic growth, control of corruption, peace and political stability and public good provision – that build support for democratic institutions. Unsuccessful democracies do not.

Importantly, we also find that support for democracy matters majorly when it comes to difficult times for democratic regimes. Hence, successful democratic performance leads to a more positive attitude from the population towards democracy, and this helps democracy to perform more successfully in the future. This virtuous cycle can be broken, however, especially when democracies start malfunctioning and this leads to a downward spiral in support for democracy.

In this light, there are several important questions for future inquiry. First, our results suggest that the decline in the support for democracy around the world is indeed a major problem, but also suggests this may be a consequence of recent failures of democratic regimes to ensure shared prosperity and fair economic and social outcomes.

Second, for both academic and policy reasons, it is critical to understand better how exposure to (successful) democracy builds support for democratic institutions.

Third and relatedly, it would be interesting to explore the role of media in this the evolution of support for democracy – for example, whether media’s depiction of the successes and failures of democratic regimes has contributed to the slide in the support for democracy.

References

Acemoglu, D, N Ajzenman, C G Aksoy, M Fiszbein, and C A Molina (2023), “(Successful) Democracies Breed Their Own Support.” Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Algan Y, S Guriev, E Papaioannou and E Passari (2017), “The European trust crisis and the rise of populism.” Available at: https://voxeu.org/article/european-trust-crisis-and-rise-populism

Deneen, P J (2019), Why liberalism failed. Yale University Press.

Edwards, S (2019), “On latin american populism, and its echoes around the world.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4): 76–99.

Fukuyama, F (2018), Identity: The demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Freedom House (2022), Freedom in the World: The global expansion of authoritarian rule.

Guiso L, H Herrera, M Morelli and T Sonno (2017), “The spread of populism in Western countries.” Available at: https://voxeu.org/article/spread-populism-western-countries

Judis, J B (2016), The populist explosion: How the great recession transformed american and european politics. Columbia Global Reports, New York.

Marantz, A (2020), Antisocial: Online extremists, techno-utopians, and the hijacking of the american conversation. Penguin books.

Mishra, P (2017), Age of anger: A history of the present. Macmillan.

Muller, J-W (2017), What is populism? Penguin UK.

Ober, J (2015), The rise and fall of classical Greece. Princeton University Press.

Snyder, T (2017), On tyranny: Twenty lessons from the twentieth century. Tim Duggan Books.

Sunstein, C R (2018), #republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press.