Evidence from Russia shows that through appropriate policy design, policymakers can overcome existing capacity challenges within bureaucracies

Editors' note: This is an updated version of a column first published in September 2017. Listen to one of the authors discuss their research in a VoxDev Talk here.

States around the world play a large role in almost every aspect of their citizens’ lives. According to World Bank data, in low- and middle-income countries, 79% of children who are enrolled in secondary school attend a public school and over half of all health spending is by public healthcare systems.1 However, while some states are effective, many are not. Strong tax enforcement means that the informal sector is only 15% of GDP in rich countries, but the median amongst low- and middle-income countries is 37% (Schneider and Enste 2002). Over 25% of teachers fail to even show up at schools in India (Chaudhury et al. 2006).

Why are some states so much more effective at implementing policy than others? Is it the people who work for the state (Jones and Olken 2005, Finan et al. 2015)? Or is it the organisations and institutions that make up the government (Bloom et al. 2015, Bertrand et al. 2019)?

Measuring state effectiveness

If you were the incoming CEO of a large, underperforming business and wanted to improve your bottom line, you might first want to know whether the bottleneck was an unskilled workforce or the way that the existing workers were managed. This kind of diagnostic is often overlooked in government (Rodrik 2010). Instead, governments, especially in low- and middle-income countries, face a constant barrage of advice on how to reform government, but little guidance on what is likely to work in their setting.

A better understanding of the sources of state (in)effectiveness would allow civil service reformers to target their efforts where returns are highest, and enable policymakers to align the design of public policy with the capacity of the bureaucracy to implement it. If we were considering restructuring a business, we would study the drivers of sales, costs, and profits. However, the state usually provides services for which markets do not provide reliable prices, and the salaries of bureaucrats are not usually set to reflect their output. How, then, can we measure the performance of the state?

Focusing on public procurement in Russia

One answer lies in focusing on particular types of state tasks that lend themselves more easily to performance measurement. A prime example is the purchase of inputs i.e. public procurement. The goal of public procurement is relatively simple: to purchase high-quality inputs at low prices. As a result, a growing number of researchers are using public procurement as a laboratory in which to study government effectiveness (e.g. Bandiera et al. 2009, Lewis-Faupel et al. 2016, Coviello and Gagliarducci 2017, Banerjee et al. 2019).

In a recent paper, we use this laboratory to study the drivers of state effectiveness and explore the scope for tailoring policy design to the capacity of the implementing bureaucracy (Best et al. 2019). We analyse detailed data on every procurement purchase in Russia between 2011 and 2016. In Russia, a vast and diverse country, each public agency makes procurement purchases independently and procurement officers typically work for multiple public agencies. Our data therefore contain tens of thousands of public agencies and bureaucrats all performing the same task independently. We also develop a way of making clean comparisons between them, focusing on purchases of off-the-shelf goods.

The performance of individual bureaucrats and organisations is key

We find that individual bureaucrats and organisations together account for over 40% of the differences between the most cost-effective purchases and the least effective ones. Of this, half comes from the impact of individuals and the other half from their organisations. Effective bureaucrats generally run more competitive auctions. They set lower reservation prices but still attract a broad pool of productive bidders. Our results also show that performance improves with experience. Surprisingly, we find no evidence that bureaucrats in regions with higher corruption are less effective, suggesting that even in highly corrupt environments, there are pockets of high state effectiveness.

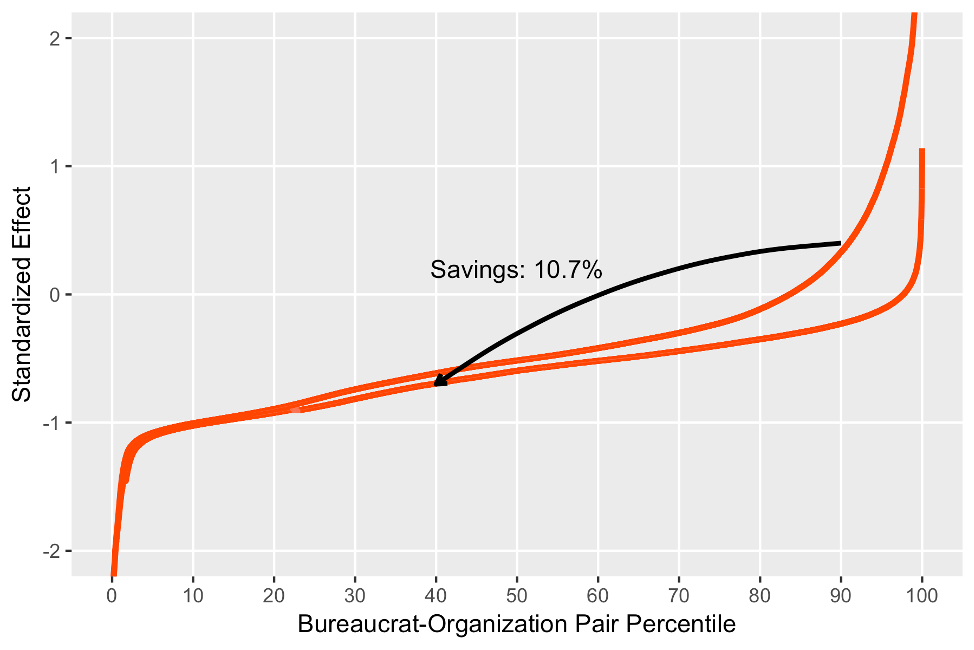

Figure 1 orders all the buyers (pairs of procurement officers and end user organisations) by their effectiveness. The buyers further to the left pay low prices, while those on the right overpay for the items they purchase. If the government were able to take the worst performing 25% of bureaucrats and organisations and place them at the 75th percentile of effectiveness, this would save taxpayers 10.7% on procurement. Since procurement totals 10% of the Russian economy, the scope for savings through improvements to the effectiveness of the bureaucracy is enormous.

Figure 1 Moving worst 25% of buyers to 75th percentile effectiveness

How policy design can help

In the short term, it is not always possible to create big improvements to the effectiveness of a large bureaucracy like Russia’s, even when the potential benefits are large. Instead we can look for levers that policymakers can pull to improve state effectiveness while taking the capacity of the bureaucracy as given. To do this, we study a series of policy changes in Russia and ask whether the accompanying changes in prices are systematically related to the effectiveness of the bureaucrats and organisations making the purchases. If they are, then it suggests that the right type of policy will differ depending on the capacity of the bureaucracy charged with implementing it.

In Russia, procurers have to use different rules to make purchases depending on what they are buying and when. In particular, as part of a range of efforts to boost domestic manufacturers, the central government ordered that auctions for purchases of certain products feature a 15% bid penalty for the supply of foreign-made goods. By comparing the purchases of each bureaucrat and organisation under the two regimes, we construct estimates of how bureaucrats and organisations affect prices under each policy.

We find that the results of changing procurement policy differ starkly depending on the effectiveness of the implementing bureaucracy. When purchasers are effective, distorting competition in the procurement process lowers supplier participation and raises prices. These findings are similar to what has been found for similar policies implemented by high-capacity bureaucracies (Marion 2007, Krasnokutskaya and Seim 2011). By contrast, when state capacity is low, tilting the playing field in favour of the weaker suppliers increases participation, and this increased competition lowers prices by up to 15%. Ineffective buyers scare away suppliers who might sell to the government, and so introducing a policy that encourages participation most when buyers are ineffective offsets the lack of bureaucratic capacity. Our results show that by designing policy appropriately, policymakers can alleviate the drawbacks of the lack of capacity within their implementing bureaucracy.

Concluding remarks: A little patience goes a long way

Our paper joins a growing body of evidence on the importance of state capacity in development (World Bank 2017). We hope that our diagnostic method for understanding its sources can be applied to a wide range of other settings. Taking the time to thoroughly diagnose the reasons why the state is not delivering policy as intended can seem like a frustrating delay when the need for reform is urgent. However, our work shows that a little patience goes a long way. It can allow difficult reforms to the civil service to be targeted where they are most impactful and policy to be written to match the abilities of the people who will actually be doing the implementing. It allows us to build a state that benefits citizens as much as possible.

References

Bandiera, O, A Prat and T Valletti (2009) “Active and Passive Waste in Government Spending: Evidence from a Policy Experiment”, American Economic Review 99(4): 1278-1308.

Banerjee, A, R Hanna, J Kyle, B A Olken and S Sumarto (2017) “Private outsourcing and competition: Subsidised food distribution in Indonesia”, Journal of Political Economy 127(1): 101-137

Bertrand, M, R Burgess, A Chawla and G Xu (2019), “The glittering prizes: Career incentives and bureaucrat performance”, Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Best, M, J Hjort and D Szakonyi (2019), “Individuals and Organizations as Sources of State Effectiveness, and Consequences for Policy Design”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11968.

Bloom, N, R Lemos, R Sadun and J van Reenen (2015), “Does Management Matter in Schools?”, Economic Journal 125(584): 647-674.

Chaudhury, N, J Hammer, M Kremer, K Muralidharan and F H Rogers (2006), “Missing in Action: Teacher and Health Worker Absence in Developing Countries”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(1): 91-116.

Coviello, C and S Gagliarducci (2017), “Tenure in Office and Public Procurement”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9(3): 59-105.

Finan, F, B A Olken and R Pande (2015), “The Personnel Economics of the State”, in A Banerjee and E Duflo (eds), Handbook of Economic Field Experiments, Elsevier.

Jones, B F and B A Olken (2005), “Do Leaders Matter? National Leadership and Growth Since World War II”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(3): 835-864.

Krasnokutskaya, E and K Seim (2011), “Bid Preference Programs and Participation in Highway Procurement Auctions”, American Economic Review 101(6): 2653-2686.

Lewis-Faupel, S, Y Neggers, B A Olken and R Pande (2016), “Can Electronic Procurement Improve Infrastructure Provision? Evidence from Public Works in India and Indonesia”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8(3): 258-283.

Marion, J (2007), “Are Bid Preferences Benign? The Effect of Small Business Subsidies in Highway Procurement Auctions” Journal of Public Economics 91(7-8): 1591-1624.

Rodrik, D (2010), “Diagnostics Before Prescription”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 24(3), 33-44.

Schneider, F and D H Enste (2002), “Shadow economies: size, causes and consequences”, Journal of Economic Literature 38: 77-114.

World Bank (2017), World Bank Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law, Washington, DC.

World Bank Open Data (2016) “Percentage of Enrolment in secondary education in private institutions” and “Health expenditure, public” (series accessed August 1 2017).

Endnotes

[1] “Percentage of Enrolment in secondary education in private institutions” and “Health expenditure, public” (series accessed 1 August 1 2017).