Connected cities request and receive 15% more funds from the national government. Yet the welfare loss from this may be only 0.24% of the budget.

Governments distribute funds across regions to finance local public goods. Ideally, funds would go to regions that most need them, and governments would treat equal regions equally. However, a common cause of concern is that ‘politically connected’ regions get more funds than others (e.g. Burgess et al. 2015, Brollo and Nannicini 2012, Hodler and Raschky 2014). If politically connected regions are being favoured – i.e. getting funds at the expense of regions that need funds more – there could be a case for delegating these decisions to non-partisan actors, or for the creation of formulas for allocation of public funds across regions.

Instead, if politicians know better those connected to them, allocation based on connections might not be harmful. Moreover, even if connections-based allocation brings gains for connected regions and losses for unconnected regions, the aggregate welfare losses might not be large enough to justify policy interventions.1

Favouritism in Brazilian grant allocation

In a recent paper (Azulai 2017), I study the consequences of one prominent form of political connections in democracies: party-based connections between local level politicians (mayors) and national politicians in charge of grant allocations.

To do so, I explore rich data from 2009-2016 containing the universe of grant requests and approvals from 27 national government ministries to Brazilian cities. Different ministries approve grant requests for different types of public goods, and these grants are a substantial component of city-level capital expenditures. This data allows me to provide evidence on the effects of political connections for a broad cross-section of public goods, in a disaggregated manner.

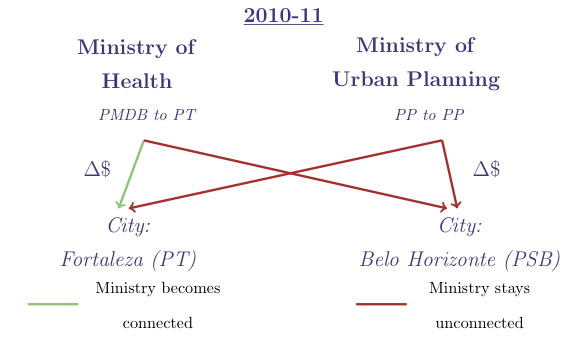

Moreover, the 27 different ministries are often allocated to different parties when national level government coalitions form – seven different parties occupy the different ministries in the typical year.2 I use this to see what happens when a new minister arrives midway through a mayoral term, and a city/mayor becomes connected with that ministry but not with other ministries. This holds fixed all city-year characteristics driving demand for grants from all ministries. The same exercise for cities not becoming connected with any ministry helps removing ministry-specific trends. The figure below illustrates the empirical strategy.

Political connections and grant allocation

When a ministry changes political party midway through a mayoral term:

- A mayor becoming connected with that ministry starts requesting 15% more funds from them, relative to ministries the mayor did not get connected with.

- Mayors start receiving 15% more funds from the ministry they became connected with, relative to ministries they did not get connected with.

This is most likely to be favouritism, as opposed to differences in information or in ideological agreement between parties. Looking at post-natural disaster grants for prevention and relief (on which there is broad political consensus), I show that when reacting to publicly known shocks to local demands (i.e. the natural disasters), cities becoming politically connected with the right ministry get 17% more funds than cities affected by the same natural disaster but not becoming politically connected.

This conclusion extends to other types of grants. There is little learning from past ministers: unconnected cities that were connected in the past get the same amount of grants as cities that are always unconnected. Grants to connected cities are also not different in terms of observable grant characteristics other than the grant size.

Political connections and aggregate welfare

With this in mind, how do we quantify the aggregate losses due to favouritism – or how much do unconnected cities lose and how much do connected cities gain? One key challenge to evaluate this is that for many types of public goods – such as sports courts or public squares – we do not have direct measures of relative needs for funds across regions. I look at the welfare losses from connections from the viewpoint of a planner that fully agrees with the ministers, except it does not favour connected cities (for one alternative, see Finan and Mazzocco 2017). This measure can be interpreted as:

- the loss faced by a non-partisan minister with a partisan allocation of funds;

- a lower bound on the social cost of partisan allocation of public funds. Society could have other sources of disagreement with ministers, and in this case, the costs of delegating decisions to these ministers would be larger.

By estimating the minister’s willingness to approve a request as a function of connections and funds requested, I can infer (1) the extent of favouritism and (2) whether large requests have a smaller return on an extra dollar. If large requests had smaller returns, connected cities with larger requests would have a smaller return on the extra dollar than unconnected cities, and welfare losses from connections would be large. In the Brazilian context, instead, estimates show this is not the case, and the welfare losses from political connections amount to 0.24% of the typical ministry’s budget for grants – or one hospital per year in a country of 5,500 cities.

Policy implications

The counterfactual non-partisan ministry does not lose much from partisanship. Yet, the partisanship of ministries does play a role in allowing for coalition formation at the national level. It is not clear then that a non-partisan minister would try to reduce partisanship in the allocation of public funds across regions, at the cost of making it harder to form government coalitions.

That being said, society could be facing much larger welfare losses from favouritism, and it could be desirable to reduce ministerial discretion – for instance, with formulas for fund allocation across regions. My paper informs on this policy issue by computing lower bounds on the welfare costs of political connections. This can be compared with the potential benefits of ministerial flexibility: out of 500,000 grant requests in these eight years, only 80,000 were approved. Without evidence that these ministers diverge from society in other respects other than political connections, we cannot reject the possibility that the welfare cost from connections is small, while the benefit of having the flexibility to reject bad grant requests is large.

References

Azulai, M (2017), “Public good allocation and the welfare costs of political connections: Evidence from Brazilian matching grants”, working paper.

Brollo, F, T Nannicini (2012), “Tying your enemy’s hands in close races: The politics of federal transfers in Brazil”, American Political Science Review 106(4).

Burgess, R, R Jedwab, E Miguel, A Morjaria, G Miquel (2015), “The value of democracy: Evidence from road building in Kenya”, American Economic Review 105(6).

Finan, F, M Mazzocco (2017), “Electoral incentives and the allocation of public funds”, working paper.

Hodler, R, P Raschky (2015), “Regional favouritism”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(2).

Endnotes

[1] Inequality concerns can be viewed as a ‘discount’ on the return on funds for the better-off cities (or a discount on the returns from connected cities).

[2] While 30% of cities are connected with a given average ministry through the last eight years – suggesting low capacity to substitute connections today with connections tomorrow – 97% of cities are connected with at least one ministry in the last eight years (so that estimates are representative of a wide set of cities).