Evidence from Brazil shows that patronage plays an important role in public sector hiring, adversely affecting the quality of the public workforce

Given the crucial role in the provision of public services that is played by a country's public sector workforce, governments should attempt to hire qualified individuals in the public sector (Finan et al. 2017). To ensure meritocracy in this selection process, civil service systems were introduced, with the goal of shielding public sector jobs from the political influences that were typical of the past.

Patronage problems

However, even in modern bureaucracies politicians retain some discretion in the selection of public workers, for instance through the use of temporary contracts (Grindle 2012). While this flexibility can be used by politicians to select individuals who are particularly qualified and motivated, it can also leave the door open to patronage: politicians may use public sector jobs to reward their political supporters. Despite the potentially significant impact of this phenomenon, we lack systematic evidence on the presence of patronage in a modern bureaucracy, limiting our understanding of its consequences for the public sector.

Patronage in Brazil

In our recent paper (Colonnelli et al. 2017), we study patronage in the context of Brazilian local governments during the 1997-2014 period. In order to conduct a systematic investigation of patronage in public employment, we construct a new dataset that allows us to track the careers in the public sector of supporters of different Brazilian parties. We combine two data sources:

- A longitudinal dataset with detailed information on the careers of all Brazilian public sector employees between 1997 and 2014.

- A dataset on more than two million political supporters of Brazilian local parties over this period. These supporters are either local politicians or campaign donors. Based on the politicians' party affiliation and the destination of the donors' contributions, we can link these individuals to the local party they support.

Favouritism

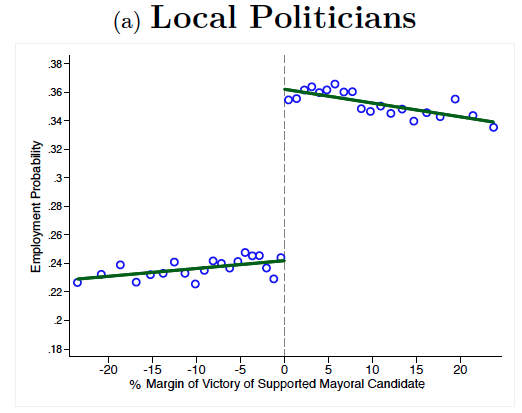

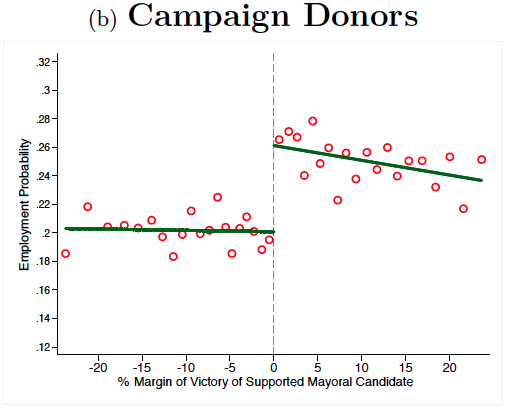

In the first step of our analysis, we show that political supporters of the party in power in a municipality are favoured in their access to public sector jobs. To establish this result, we compare the public sector careers of supporters of a municipality's elected mayor with those of supporters of the losing mayoral candidate, focusing on municipalities where the margin of victory of the winning party over the runner-up is extremely small (5 percentage points or less). We find that being a political supporter of the party in power increases the probability of being employed in the public sector by 12.4 percentage points (or 51%) among local politicians and by 6.7 percentage points (or 33%) among local campaign donors.

Figure 1

Notes: The figure shows the average public sector employment probability in the four years after the election, by bins of the margin of victory of the mayoral candidate supported over the opponent. Supporters whose supported mayoral candidate lost have a negative margin of victory, while supporters of the winning mayoral candidate have a positive margin of victory.

Political favouritism in public hiring is a widespread phenomenon across the whole Brazilian public sector hierarchy. We find that political supporters are granted significant preferential access to jobs from the top to the middle tiers of the bureaucracy, and also to jobs as front-service providers.

The importance of patronage

In the second step of our analysis, we use detailed information on the characteristics of supporters and jobs to show that patronage is the crucial channel behind this political favouritism. These individuals are rewarded for their support, and the provision of political support substitutes an individual's quality as a hiring criterion.

We show that, consistent with a quid pro quo mechanism, the extent of preferential access to public jobs and the associated monetary returns, are increasing in an individual's amount of support provided to the party in power. Support is measured by the amount of money donated or by the number of votes contributed to the party. At the same time, we find that supporters of the party in power are screened less on qualifications i.e. their education or previous private sector wages.

We also provide direct evidence inconsistent with alternative interpretations of this political favouritism in public sector hiring. Indeed, political parties do not seem to be screening their supporters on hard-to-observe dimensions of ability. Similarly, we find evidence that is hard to reconcile with political favouritism stemming from politicians' attempts to increase the ideological alignment between public workers and the party in power.

The effect of patronage on public service provision

In the final part of the paper, we provide suggestive evidence that patronage is associated with a worse provision of public services. We analyse the quality of primary education provided by Brazilian municipalities (one of the main responsibilities of these local governments). We show that an increase in the extent of patronage in a municipality is associated with lower student test scores in the local public schools.

Implications

Our paper documents that, far from being a phenomenon of the past, patronage can still play an important role in public sector hiring. Granting some hiring discretion to politicians may still be beneficial e.g. by improving agency relationships between politicians and some layers of the bureaucracy. However, our results indicate that the way in which this discretion is used should be monitored more closely. This will avoid that the provision of political support substitutes for the qualifications of potential hires, which lowers the average quality of the public workforce.

Editors' note: This column is based on this PEDL project.

References

Colonnelli, E, M Prem, and E Teso (2017), "Patronage in the allocation of public sector jobs", working paper.

Finan, F, B Olken, and R Pande (2017), “The personnel economics of the developing state”, Handbook of Economic Field Experiments, pp. 467-514.

Grindle, M (2012), Jobs for the boys: Patronage and the state in comparative perspective, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.