Allowing workers to signal their ability more easily increases access for the poor and alleviates labour constraints faced by small firms in Ghana

Two of the most ubiquitous features of economic activity in low- and middle-income countries are that the vast majority of firms are very small and that young people experience higher rates of unemployment than others (Hsieh and Olken 2014, Garcia and Fares 2008). Small firms are less productive than their larger counterparts and rarely grow; many of their would-be workers join growing cohorts of unemployed and underemployed youth with limited access to formal employment. This led us to examine whether there are features of the labour market that limit hiring and what those features are.

Investigating labour and hiring constraints

We studied (Hardy and McCasland 2023) a government program in Ghana that randomly placed young unemployed people as apprentices with small firms and included no cash subsidy to firms (or workers) beyond in-kind recruitment services. The program focused on five skilled crafts: garment-making, hairdressing, carpentry, welding, and masonry. Once placed, the young people would work and train as normal, learning the craft and earning a wage similar to any other employees working as apprentices.

There were more firms than would-be workers expressing their interest to participate in the worker placement program, generating random variation as to whether a firm received any placement workers and the number of placement workers received. This was conditional on the geographic feasibility of a match between worker and firm. We use this random variation in the number of workers placed with each firm in the study (which varies from zero to five apprentices) to understand whether labour market frictions constrain hiring.

Evidence of labour constraints

Like most programs targeting unemployed workers, many workers who initially expressed interest in the program did not ultimately report to their new jobs; slightly more than half of the placed workers reported to work. Accordingly, in the firms in our sample, each additional worker placement increased total employment in the firm by slightly more than half a worker. This finding implies two things. First, firms assigned program apprentices did not substitute away from other employment by restricting additional hiring or firing of existing workers. Second, firms that were not assigned apprentices through the program did not increase their firm size through other means, by retaining existing workers longer than planned or hiring additional employees beyond their baseline firm size.

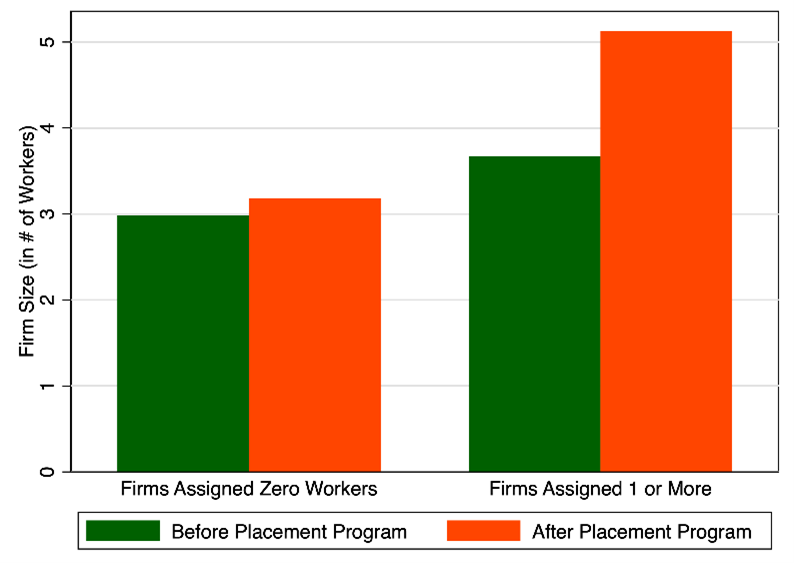

Figure 1: Firm size before and after placement program

Notes: Presented above are raw average firm sizes for firms assigned zero workers and firms assigned one or more workers before and after the placement program. In the paper, we include fixed effects that control for the randomisation (which was a function of geographic feasibility/apprentice preferences; some firms were more likely to be randomly assigned more workers than others which is controlled for with these fixed effects). We also include fixed effects for district, craft, and follow-up round. In addition, the main specifications in the paper use number of workers assigned as the treatment variable, such that impacts can be interpreted as the impact of being matched with a marginal would-be apprentice across firms with similar level of interest from would-be apprentices. Please refer to the paper for exact point estimates.

The second key test of the paper is whether experimentally increasing firm size also increases profits. If the placement experiment increased both employment and profits, that would be evidence that labour market frictions like hiring costs constrain firm growth and keep employment sub-optimally low in the absence of intervention. Indeed, we find that each worker placement generates a 10% increase in monthly firm profits.

Crossing hurdles to access and gain entry to apprenticeships

To help us understand what type of labour market imperfection constrains hiring in our sample, we critically analysed the existing apprenticeship institutional context through a series of qualitative interviews preceding the experiment. In Ghana, inexperienced workers often pay an entrance fee to firms to gain employment as apprentices. Our baseline survey with firm owners included questions designed to help us learn more about this informal arrangement and why it might be structured the way it is. Firm owners nearly universally explained the entrance fee as a tool for screening workers. 85% said they normally charge an entrance fee to require would-be apprentices to signal investment in the apprenticeship. The most common response is that firm owners are looking for apprentices who are “serious”, which in this context signifies a combination of ability to learn and motivation. Only 8% of firm owners in the baseline survey mentioned using the fee to either finance training supplies or compensate for the firm owner’s training time. Less than 1% reported using the fee to finance apprentice wages throughout the apprenticeship.

Building on this qualitative evidence, we understand our results through a stylised model in which only would-be apprentices with an aptitude for the craft are willing to pay the entrance fee. In this setting, wages are proportional to worker aptitude in the sense that most apprentices’ contracts are functionally a wage equivalent to a small share of firm revenues. Only those would-be workers with an aptitude for the craft can expect to earn enough to justify the payment of the initial entrance fee. The entrance fee allows firm owners to screen out would-be workers with a low aptitude for the craft and hire only would-be workers with a high aptitude for the craft. On the other hand, the government worker placement program required would-be workers to go through a lengthy application process, which served as a time-based rather than a money-based entrance fee. Similarly, it would follow from this that only the would-be workers with an aptitude for the craft can be expected to earn enough to justify the long-time requirement of the initial inclusion in the government program.

Screening for high quality workers

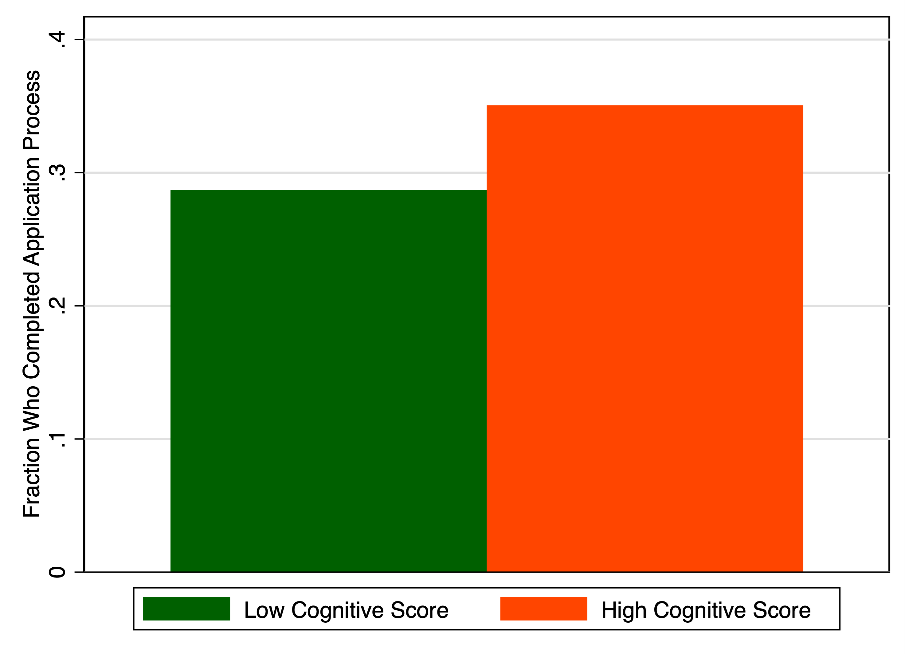

Fortunately, the study has access to information on both would-be workers who started but did not finish the application process to the government program and would-be workers who finished the application process and entered the placement program (to be matched with a firm). If indeed the lengthy government program application process served as a time-based signal of would-be worker quality, we can test for whether the applicants who made it through the process appear to have high skill aptitude. Using a measure of ability from the would-be worker baseline survey that tested abstract cognitive ability and math and vocabulary skills, we show that workers with higher measured general ability were more likely to pay the time-based entrance fee by completing the full application process. Firms are thus able to recruit higher ability workers through this program.

Figure 2: Would-be workers’ application completion rates

Notes: Presented above are raw average application completion rates among would-be workers above and below the median score on an index of cognitive skills. In the paper, we include fixed effects for district and craft, as well as other controls for non-cognitive skills. Please refer to the paper for exact point estimates.

Policy implications

Using a non-monetary signal of worker interest and ability allows would-be workers who cannot afford to pay a monetary entrance fee to gain employment through apprenticeship. Indeed, a related paper, Hardy et al. (2019) shows that the government placement program disproportionally created opportunities for poor would-be workers to gain employment, relative to less poor would-be workers. In other settings in which ability to pay is low, many have found that even very small positive prices dramatically reduce access – for example the case of insecticide treated bednets in Cohen and Dupas (2011). This project found evidence that non-monetary screening mechanisms increase access for the poor.

Several papers show that small firms suffer from credit constraints (e.g. de Mel et al. 2008). This project was among the first to show that small firms also suffer from labour constraints, and thus interventions that target labour market imperfections or natural dynamic changes in the labour market making it easier for would-be workers to signal quality to potential employers could allow small firms to grow over time.

References

Cohen, J and P Dupas (2010), “Free Distribution or Cost-Sharing? Evidence from a randomized malaria experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(1): 1–45.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie, and C Woodruff (2008), “Returns to Capital in Microenterprises: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4): 1329–1372.

Garcia, M, and J Fares (2008), Youth in Africa’s Labor Markets, World Bank Publications Number 6578.

Hardy, M, I Mbiti, J McCasland, and I Salcher (2019), “The Apprenticeship-to-Work Transition”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8851.

Hardy, M and J McCasland (2023), “Are Small Firms Labor Constrained? Experimental Evidence from Ghana”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15(2): 253-284

Hsieh, CT, and B Olken (2014), “The Missing Middle”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, American Economic Association, 28(3): 89–109.