Low-cost interventions that help young people search for employment can improve access to formal and stable jobs, raising equity in the labour market

The inclusion of youth in the labour market is a top policy priority across the world, and an especially important one in Africa. There are almost 200 million people aged between 15 and 24 in Africa, the youngest population of any continent in the world. These young people are more educated and more likely to live in cities compared to previous generations. If employed productively, they can be an engine for growth for the whole continent.

However, the inclusion of young people in the labour market has so far proven to be a challenge. In the middle-income economies of Africa, youth unemployment rates are very high. In the poorest countries, on the other hand, young people can find precarious and informal jobs relatively easily, but struggle to secure stable and satisfactory employment (OECD 2015, Feng et al. 2017). In Addis Ababa, for example, young people below the age of 30 make up half of the workforce, but take up two thirds of the temporary jobs.1 Yet, permanent jobs with open-ended contracts are valued highly.2 A recent policy report on youth employment in Africa offers a clear summary of this situation – there are “too many bad jobs in low-income countries, and too few jobs in middle-income countries” (African Development Bank 2012).

Challenges faced by youth in the labour market

Recent research in economics points to two key obstacles that young people face in labour markets. First, young people lack the resources to cover the financial costs of searching and applying for jobs. In large cities, a jobseeker often needs to travel across wide and congested areas to acquire information about vacancies and to make job applications. Without the required financial resources, it is simply not possible to search broadly and effectively. Second, young people lack credentials. Jobseekers without previous work experience or recognised educational qualifications find it hard to convince firms to hire them, even if they are skilled and would make good employees. As a result of these hurdles, young jobseekers find it particularly hard to secure good jobs and to use their talents productively.

Unfortunately, we know too little about how to remove these obstacles in practice. A first wave of experimental trials of active labour market policies (ALMPs) in developing countries has shown that these interventions have modest and often insignificant effects on employment (McKenzie 2017). However, these trials have not typically attempted to uncover impacts on the types of jobs that treated jobseekers obtain, a key outcome in low-income economies. Further, they have rarely focused on representative samples. This leaves open the possibility that such interventions may have large impacts on specific groups of jobseekers and, thus, may be effective if well targeted (Bertrand et al. 2017).

The study: Active labour market policies and youth employment

In our recent paper, we advance the discussion on active labour market policies in low-income countries by studying whether these policies can help young people to access better employment opportunities (Abebe et al. 2017). Further, leveraging a large and heterogeneous sample, we investigate whether the modest average employment effects documented in the previous literature mask stronger impacts for specific groups of disadvantaged workers, justifying better targeting and boosting the value of such policies on equity grounds.

We do this by testing and comparing the effects of two different interventions that reduce two key search frictions faced by young workers – the cost of job search and the inability to signal skills.

- The first intervention is a transport subsidy. Job search in Addis Ababa requires regular trips to the centre of town, where formal jobs are advertised, and we calibrate the subsidy amount to cover the cost of this journey. Participants can collect the subsidy from an office located in the centre of the city, up to three times a week.

- The second intervention is a job application workshop. Participants are offered orientation on how to make effective job applications using CVs and cover letters, and on how to approach job interviews. Further, we certify their general skills using a mix of standardised personnel selection tests. We worked with a trusted education institute to implement this intervention.

Our interventions are cheap – the marginal cost of offering the treatment to one individual is about US$19.80 for the transport intervention, and $18.20 for the workshop.

We evaluate these programmes using a large sample of over 3,000 young people (aged 18 to 30) who were without permanent work at the beginning of the study. To construct this sample, we generated census lists of all young people without permanent work who lived in randomly selected neighbourhoods across the city (excluding the city centre). We randomly selected study participants from these lists, and then randomly assigned some participants to receiving either of the interventions.

Evidence: Impact on formal employment and earnings

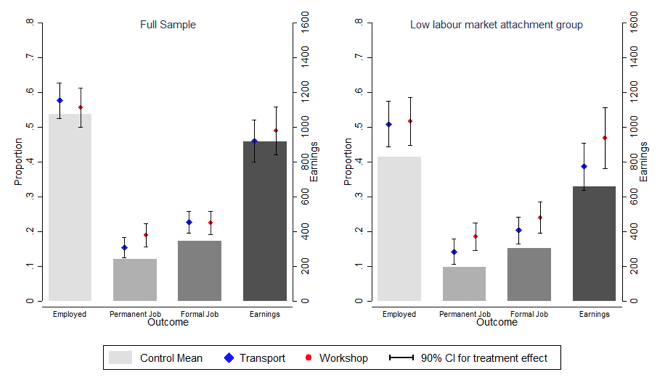

We find large and highly significant impacts of both treatments on the probability of finding a good job (defined in terms of stability and formality). Eight months after the end of the programme, individuals in both treatment groups are 31-32% more likely to be in formal employment than individuals in the control group. Further, individuals invited to the job application workshop are almost 60% more likely to have permanent work. This reduces the gap in permanent employment between youth and older workers by more than 20%.

Further, we find significant impacts on employment and earnings among the workers with the worst employment prospects. Consistent with the previous literature, the average treatment effect on the probability of having a job for the entire sample is not significantly different from zero. However, this masks considerable heterogeneity. We identify the jobseekers that face the worst employment prospects in the market using baseline characteristics and the techniques recommended in Abadie et al. (2016). For those with the worst employment prospects, we find that overall employment goes up by about 25% (for both interventions) and monthly earnings grow by 40% (for the application workshop). This suggests that even in low-income economies, some workers do not have unrestricted access to employment opportunities.

On average, the cost of placing one individual with low labour-market attachment in a job is $174. This compares favourably with the cost of alternative interventions. For example, in Ethiopia, a recent cash transfer programme has offered individuals $300 per year, generating increases in earnings of about 33% (Blattman and Dercon 2017). Further, the impacts of the workshop on earnings imply that, for the subgroup with low labour market attachment, the cost of this intervention is paid back via higher earnings within less than two months.

Figure 1 Treatment effects and control group means, for different samples

Finally, we explore the mechanisms underlying our results and we show that both interventions work by increasing search efficacy, albeit in very different ways. The workshop improves the quality of the information contained in each application. This is particularly beneficial to the least skilled, who are less able to rely on well-recognised forms of certification. On the other hand, the transport subsidy significantly increases the number of trips jobseekers make to look for work, expanding the amount of information available about open vacancies. This allows jobseekers to target their job applications more selectively, increasing their application success rates.

These results suggest that workers may have private information about their suitability for particular jobs, which helps us understand why interventions that do not leverage this information (e.g. job fairs or direct matching) may be relatively ineffective. In a companion paper (Abebe et al. 2017a), we confirm this hypothesis in the context of a job fair intervention in Addis Ababa.

Policy lessons: Labour market policies help the most disadvantaged

While our results are consistent with the view that ALMPs in developing countries are unlikely to have large average effects on overall employment, we document that such policies can have clear impacts on helping young workers to get better jobs. Furthermore, we show that such impacts are strongest among the most disadvantaged – who also experience an increase in the overall likelihood of employment and a boost in earnings – with positive implications for equity and social inclusion. What is particularly appealing about these interventions is their relative affordability.

References

Abadie, A, M M Chingos and M R West (2016), “Endogenous stratification in randomized experiments”, Working paper.

Abebe, G S C, M Fafchamps, P Falco, S Franklin, S Quinn (2017), “Anonymity or distance? Job search and labour market exclusion in a growing African city”, Working paper.

Abebe, G S C, M Fafchamps, P Falco, S Franklin, S Quinn, F Shilpi (2017a), “Job fairs: Matching firms and workers in a field experiment in Ethiopia”, Working Paper.

African Development Bank (2012), African Economic Outlook: Promoting Youth Employment in Africa.

Bertrand, M, B Crepon, A Marguerie and P Premand (2017) “Contemporaneous and post-program impacts of a public works program: Evidence from Cote d'Ivoire”.

Blattman, C and S Dercon (2016), “Occupational choice in early industrializing societies: Experimental evidence on the income and health effects of industrial and entrepreneurial work”, Working paper.

CSA (2014), “Key Findings on the 2014 Urban Employment Unemployment Survey”, Central Statistical Authority (CSA) of Ethiopia.

Feng, Y, D Lagakos and J Rauch (2017), “Unemployment and development”, Working Paper.

OECD (2015), "Enhancing job quality in emerging economies", in OECD Employment Outlook 2015, Paris: OECD Publishing.

Endnotes

[1] Authors’ calculations using data from CSA 2014.

[2] In our data, young people are almost twice as likely to report that they would like to stay in their current job in the long run if the job has an open-ended contract.