While technical skills training increases overall employment in the short term, soft skills training increases employment and earnings in the long term

Given the centrality of labour market outcomes for the well-being of individuals and households around the globe, policymakers are growing increasingly interested in the role of vocational training in helping to improve the transition from formal schooling to employment. Still, whether or not vocational training programmes succeed in improving the labour market outcomes of their participants is highly debated. Empirical evaluations of vocational programmes report mixed results: while some programmes suggest positive and sustained impacts (Kugler et al. 2020, Silliman and Virtanen 2019, Brunner et al. 2019, Attanasio et al. 2017, Attanasio et al. 2011), others report no effects (Hicks et al. 2014). Moreover, even the positive effects of some vocational programmes, that succeed in improving labour market outcomes in the short term, can dissipate in only a few years (Acevedo et al. 2017, Alzua et al. 2016, Hirshleifer et al. 2016).

A common explanation for the short-lived returns to some of these vocational programmes is that the narrow focus of these programmes may not provide the flexibility required to adapt to changes in the nature of work (Hanushek et al. 2017, Krueger and Kumar 2004). In particular, as we live in a period characterised by rapid technological change (Brynjolfsson and McAffee 2011), economists argue that general – rather than narrow – skills better equip people in adapting to labour market changes (Goldin and Katz 2009, Acemoglu and Autor 2011, Goos et al. 2014, Deming and Noray 2020). Interestingly, social skills are seen as central amongst these increasingly important general skills (Deming 2017). Despite the excitement around the role of social skills in allowing workers to adapt to labour market changes, there remains little credible experimental evidence on whether social skills training can lead to sustained labour market returns.

Experimenting with social skills

In our recent paper (Barrera-Osorio et al. 2020), we report the results from an experiment we designed to test whether or not social skills can, in fact, help sustain the labour market returns of vocational programmes. Working with the Carvajal Foundation, we implemented our experiment as part of the Inclusive Employment Program (IEP) in Cali, a large city in Colombia. The target population of the programme were individuals from low-income households and communities. The courses were all in the service sector in each of the following areas: sales and client services, general services, surveillance and security, cashiers, quality control, cooking, delivery, and storage assistant.

To isolate the relative impact of hard (technical) versus soft (social) skills in vocational training, we randomly assigned applicants to otherwise identical, oversubscribed vocational programmes – varying the intensity of hard versus soft skills training. For the same course, some individuals were randomly assigned to a track of 100 hours of technical training (hard skills) and 60 hours of soft training (social skills); other individuals were randomly assigned to a track of 100 hours of soft training and 60 hours of technical training. Since programmes are oversubscribed, we also had one set of applicants who did not receive a place in a vocational programme to serve as a control group.

We combined our own baseline and endline survey results with high quality administrative data from national social security records. We followed the outcomes of applicants to these vocational programmes, keeping a close eye on their subsequent labour market performance.

Large overall returns to vocational training

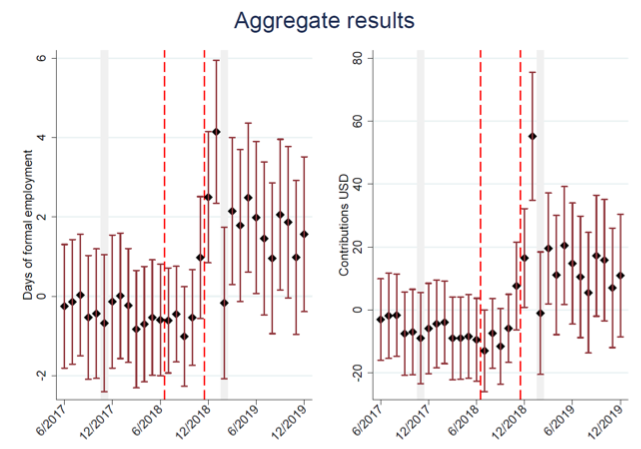

On aggregate, we find large, sustained returns to vocational training. The programme pays for itself in about seven months. This is evidenced in our administrative data by increases in days and months of employment, as well as increased social security deposits – a proxy for formal sector wages (Figure 1). Our survey data complement our administrative data and show that vocational training improves organisational skills. Our survey data also suggests that while these results are partly driven by a shift into the formal sector, vocational training increases aggregate employment by five days a month, or seven days a week when we include data from the informal sector.

Figure 1 Aggregate results of vocational training

Social skills and labour market dynamics

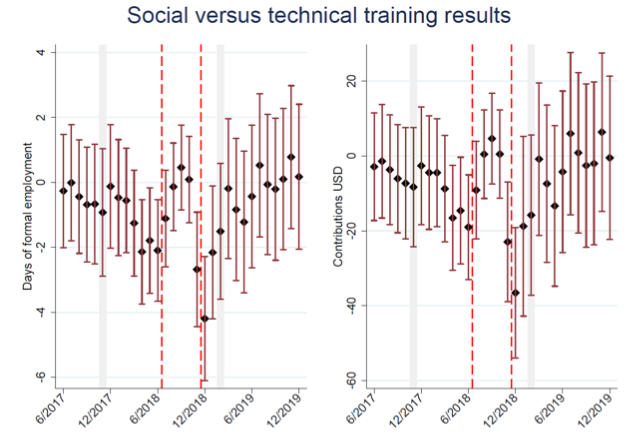

Next, we look at the effects of hard versus soft skills in vocational training on labour market dynamics. We find a larger initial increase in employment resulting from the programme emphasising technical skills, but we also see that these benefits appear to dissipate with time, whereas for the training emphasising social skills this does not look to be the case. We then formally test whether or not there are dynamics in formal employment, days worked and wages of applicants randomised into the different programmes, and find that they are statistically different from each other (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Social versus technical training results

Constraints to participation

As part of the experiment, we also sought to understand whether resource constraints might prevent individuals from enrolling in vocational programmes – even if these programmes offer potentially large rewards. To do this, in a second level of randomisation, we provided half the participants in both the hard and soft skills programmes with a stipend to cover transport costs. Highlighting the importance of resource constraints, we found larger effects of vocational training for those who received stipends. We also examined gender differences in the returns to vocational training, and found that men experienced heightened benefits from the programme. This suggests that skills alone may be insufficient in helping women overcome other barriers to employment such as a lack of access to childcare.

Adding to the evidence base

Our paper provides some of the first evidence directly testing whether or not combining narrower technical training with general skills components can help sustain labour market returns in the longer term (Acemoglu and Autor 2011, Deming 2017, Deming and Noray 2020). Additionally, it may help provide clues as to why prior studies of vocational programmes reported such mixed results – helping to explain why some vocational programmes from around the world that have general skill components provide long-run benefits (Kugler et al. 2020, Silliman and Virtanen 2019, Brunner et al. 2019, Attanasio et al. 2017, Attanasio et al. 2011).

Our results also offer insights to policymakers considering the role of vocational training in making their labour market opportunities more equal. Vocational training can help boost employment prospects, and with general skills components, might be able to provide sources of long-term rewards. We also find that, particularly in lower- and middle-income contexts, resource constraints may prevent individuals from making investments in vocational training.

References

Acevedo, P, G Cruces, P Gertler and S Martinez (2017), “How job training made women better off and men worse off”, NBER Working Paper No. 23264 (forthcoming in Labour Economics).

Acemoglu, D and D Autor (2011), “Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings”, in Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4, pages 1043-1171, Elsevier.

Alfonsi, L, O Bandiera, V Bassi, R Burgess, I Rasul, M Sulaiman and A Vitali (2017), “Tackling youth unemployment: Evidence from a labor market experiment in Uganda”, STICERD-Development Economics Papers.

Attanasio, O, A Guarin, C Medina and C Meghir (2017), “Vocational training for disadvantaged youth in Colombia: A long term follow up”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2): 131-143.

Attanasio, O, A Kugler and C Meghir (2011), “Subsidizing vocational training for disadvantaged youth in Colombia: Evidence from a randomized trial”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(3): 188-220.

Barrera-Osorio, F, A Kugler and M Silliman (2020), “Hard and soft skills in vocational training: Experimental evidence from Colombia”, NBER Working Paper No. 27548.

Brynjolfsson, E and A McAfee (2011), Race against the machine: How the digital revolution is accelerating innovation, driving productivity, and irreversibly transforming employment and the economy.

Brunner, E, S Dougherty and S Ross (2019), “The effects of career and technical education: Evidence from the Connecticut technical high school system”, EdWorking Paper No. 19-112, Annenberg School, Brown University.

Deming, D J (2017), “The growing importance of social skills in the labor market”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 132(4): 1593-1640.

Deming, D J and K Noray (2018), “Stem careers and technological change”, NBER Working Paper No. 26092.

Hicks, J H, M Kremer, I Mbiti and E Miguel (2015), Vocational education in Kenya—A randomized evaluation, 3ie Grantee Final Report. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie).

Goldin, C and L Katz (2009), The Race Between Education and Technology, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goos, M, A Manning and A Salomons (2014), “Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring”, American Economic Review, 104(8): 2509-26.

Krueger, D and K B Kumar (2004), “Skill-specific rather than general education: A reason for US-Europe growth differences?” Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2): 167-207.

Kugler, A, M Kugler, J Saavedra and L O Herrera-Prada (2020), “The long-term impacts and spillovers of training for disadvantaged youth”, Journal of Human Resources, forthcoming.

Silliman, M and H Virtanen (2019), “Labor market returns to vocational secondary education”, ETLA Working Papers. No 65.