The New Deal’s youth employment programme, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), had significant long-run benefits, increasing the lifetime earnings and longevity of its participants, despite having few effects on short-term labour market outcomes.

Disclaimer: Any findings, views, or opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve System, or Social Security Administration, or any agency of the federal government.

During recessions, especially deep ones such as the Great Depression, governments often implement programmes to help affected populations. A substantial body of research has studied whether these large public relief programmes were effective (e.g. Fishback 2017). But these studies typically investigate the impacts of aggregate expenditures on the short-term outcomes of the entire population, rather than on participants. Moreover, as the youth usually suffer from higher unemployment rates during recessions, they are frequently targeted by these programmes. A large literature has investigated the efficacy of youth employment programmes (e.g. Card, Kluve and Weber 2019), and has found that these programmes appear to have modest effects on labour market outcomes in the short-run. However, evaluations have not typically followed participants over a long period of time, and they often ignore non-labour market effects.

In our research (Aizer et al. 2024), we conduct the first lifetime evaluation of the New Deal’s youth employment programme—the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was the largest youth employment programme in U.S. history. Tracking participant outcomes in the short- and long-term, we examine how the programme affected labour, health, and geographic mobility both shortly after the programme, and over the course of participants’ lives.

We find that the CCC had significant positive impacts. Focusing on short-term labour market outcomes, however, does not provide the full picture of potential benefits to participants: effects on both income and health only manifest themselves fully over the lifetime.

Background on the Civilian Conservation Corps and our analysis

During the Great Depression, youth employment rates peaked at approximately 60%. The CCC was created to provide young, unemployed American men ages 17-25 with work opportunities to improve public land and infrastructure. Men in the CCC built or restored roadways, dams and other infrastructure that Americans have come to rely on in the 20th century and beyond. They also worked on soil conservation efforts as well as improving national parks including Yosemite and the Grand Canyon. More than 3 million men served in the programme, which operated from 1933 to 1942.

The rationale for the creation of the CCC was that the programme would provide much needed job training, work experience, and a sense of purpose to the enrollees, who were drawn from poor American families already receiving relief during the Depression. Enrollees were sent to military-run camps around the country. In exchange for their labour, they were housed, fed, trained (often also educated), and paid around $30 per month, of which $25 was sent home to their families. Individuals were enrolled for six-month terms with an opportunity to re-enroll for a maximum of four terms.

To study the short- and long-term effects of the programme, we created a new individual-level dataset of CCC participants that follows them from the time they enrolled until their death. We digitized application and discharge records for more than 20,000 CCC participants in Colorado and New Mexico. We then matched these records to the 1940 Decennial Census and to World War II enlistment records to obtain information on short-run outcomes such as wages and employment, education, height and weight. We also matched individuals to Social Security Administration (SSA) benefit records to determine their lifetime earnings, age at retirement and disability rates. Finally, we matched individuals to death records to determine their age at death.

Using this newly compiled dataset, we investigated the effect of service duration on all of these short-term and lifetime outcomes.

Positive outcomes of youth employment programmes over the lifetime

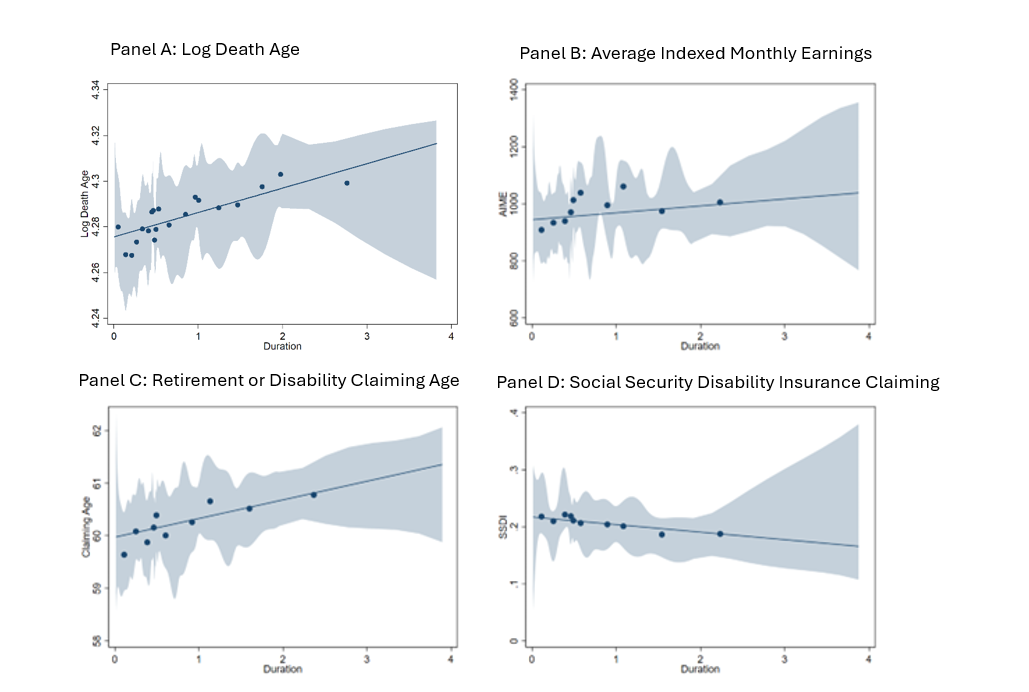

As shown in Figure 1, we find positive relationships between service length and lifetime economic and health outcomes. An additional year of service duration leads to one more year of life, $67 higher average monthly earnings (a 7% increase relative to the sample average), delays of half a year in claiming either retirement or disability benefits, and a 10% decline in disability claims.

Figure 1: CCC participation and long-term outcomes

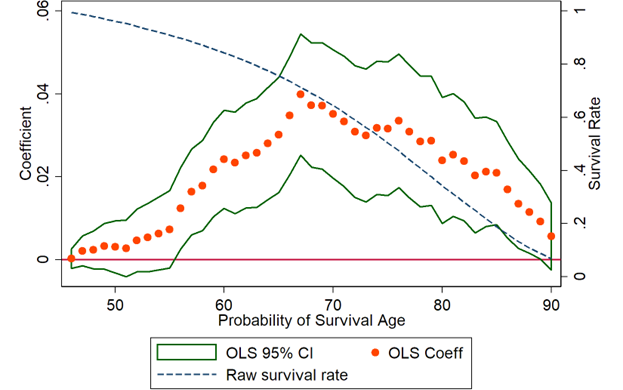

Moreover, we find that the longevity gains are not accrued evenly across the lifespan. In Figure 2, we plot the effect of an additional year of service on the probability of surviving to a certain age. Much of the gains in survival occurs after age 55, exactly when the general population experiences a decline in the survival rate.

Figure 2: Effects of CCC participation on survival to specific ages

But short-term effects of the New Deal’s youth employment programme are mixed

In line with other studies on the efficacy of youth jobs training programme (Card, Kluve, and Weber 2018, Kluve et al. 2019), and in contrast to the lifetime impacts, we find that the short-term effects on labour force participation, wages, and employment are little to none.

However, when we look at non-labour outcomes, we see a significant effect of the programme. An additional year of service leads to a height growth of about one inch, 0.17 years of additional schooling, and increases the likelihood of moving to healthier, richer areas of the county. The height results may be surprising at first glance, but given the severe deprivation of the Great Depression and the participants’ young age, the nutrition gains during the programme contributed significantly to additional growth.

Using a modern randomised experiment to refine our estimates

The goal of our study was to determine the causal impacts of longer service in the CCC on lifetime outcomes. Such an evaluation is ideally conducted using a randomised controlled trial (RCT). But for our historical programme only observational data is available. As a result, any association between training duration and outcomes might be driven by differences in the types of individuals who trained for longer or shorter periods. For example, rather than improving the health of participants (a causal impact), healthier individuals might have served for longer (a selection effect), biasing our estimates of the impacts of the programme.

To correct for this bias, we extend econometric techniques developed by Athey, Chetty, and Imbens (2020): we use short-term estimates of the impacts of the programme from an RCT to correct the bias in our long-term programme impacts based on observational data. Specifically, with the experimental data, one can compare short-term estimates that exploit the randomisation (and are therefore unbiased estimates) with estimates that do not (and are therefore potentially biased estimates). This comparison generates a measure of the extent of the bias, which we can use to correct our long-term estimates based on historical, observational data.

To implement this method, we exploit exogenous variation in the modern-day Job Corps (JC) RCT. Using the JC RCT is ideal because JC training is modeled on the CCC programme and thus it can inform us on the short-term impacts of this kind of training. Schochet, Burghardt, and McConnell (2008) conducted an evaluation of the RCT of the JC programme on short-term labour outcomes. Using the results from the RCT, we construct a measure of the potential bias in estimates that do not exploit randomisation and use this to adjust our non-experimental estimates of the short and lifetime impacts of the CCC. Even after this adjustment we find substantial improvements in lifetime economic and health outcomes.

Short-term labour outcomes may not tell the whole story

This study provides two main lessons for academics and policymakers.

First, short-term labour market measures often reflect periodic market fluctuations and do not incorporate gains from experience or the benefits from health and migration. As a result, point-in-time measures of labour market outcomes typically studied in job training evaluations can only provide a partial and possibly biased assessment of training programme effects.

Second, the lifetime health benefits of the programme are substantial. We calculate the Marginal Value of Public Funds (MVPF) following the approach by Hendren and Sprung-Keyser (2020). If we used the short-term impacts only, the MVPF would be below 1—suggesting that beneficiaries' willingness to pay for the programme is smaller than the net cost to the government. But this MVPF is 6.0 when we include the willingness-to-pay for increases in longevity, disability reductions, and increases in claiming ages. Thus our ability to track the health benefits of the programme over the long term changes our evaluation of its cost-effectiveness.

Open questions

Despite these large benefits, we estimate that the programme did not fully compensate participants for the losses they suffered during the Great Depression. Future research should assess the effects of other programmes, either alone or in combination with CCC.

Another important question for future research is whether there exist short-term markers that can be used to predict long-term gains. If so, this would provide policymakers, who are often constrained by short-term budget and other considerations, with better evidence regarding likely lifetime benefits.

References

Aizer, A, N Early, S Eli, G Imbens, K Lee, A Lleras-Muney, and A Strand (2024) "The Lifetime Impacts of the New Deal's Youth Employment Program." The Quarterly Journal of Economics, qjae016.

Athey, S, R Chetty, and G Imbens (2020), "Combining Experimental and Observational Data to Estimate Treatment Effects on Long Term Outcomes," Working Paper.

Card, D, J Kluve, and A Weber (2018), "What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations," Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(4): 894–931.

Fishback, P (2017), "How Successful Was the New Deal? The Microeconomic Impact of New Deal Spending and Lending Policies in the 1930s," Journal of Economic Literature, 55(4): 1435–1485.

Hendren, N, and B Sprung-Keyser (2020), "A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(3): 1209–1318.

Kluve, J, S Puerto, D Robalino, J M Romero, F Rother, J Stöterau, F Weidenkaff, and M Witte (2019), "Do Youth Employment Programs Improve Labor Market Outcomes? A Quantitative Review," World Development, 114: 237–253.

Schochet, P Z, J Burghardt, and S McConnell (2008), "Does Job Corps Work? Impact Findings from the National Job Corps Study," American Economic Review, 98(5): 1864–1886.