Jobs in Peru use a larger number of skills than comparable jobs in the US. This lack of specialisation is consistent with firms’ hiring of "toderos" (workers with many skills, do-it-alls), given the high levels of worker reallocation.

Labour markets in poorer countries are characterised by higher worker reallocation rates (Donovan et al. 2023). In richer economies, a dynamic labour market that seamlessly reallocates workers to jobs goes hand in hand with robust productivity growth and sustained income growth (Hopenhayn and Rogerson 1993, Foster et al. 2001, Davis and Haltiwanger 2014). Instead, in poorer countries, the brisk pace of reallocation is accompanied by high unemployment and under-employment risk and lower returns to human capital (Feng et al. 2024, Lagakos et al. 2018).

In our research (Atencio-De-Leon, Lee, and Macaluso 2024), we explore why fast-reallocating labour markets do not yield productivity enhancements. To do so, we use detailed microdata to provide new evidence on disparities in detailed job skills between a rich and a poorer country. While a preference for workers who are generalists is a response to an economic environment with a high turnover rate, the lack of specialisation limits productivity growth.

Survey of skills and employers recruiting behaviour (SSERB) in Peru

In the US, the O*NET skill survey provides detailed information on the average importance and level of large set cognitive and non-cognitive skills, as reported by workers, managers, and occupational experts for each occupation. On the other hand, there are no data sources to study the skill content of jobs in poor countries. To remedy the dearth of data, we therefore conducted a similar survey with a nationally representative sample of workers and firms in urban Peru. Managers were asked to reflect on the performance of a specific employee’s occupational tasks and report the importance of nine skills (cognitive, social, organisation, writing, customer service, project management, people management, financial skills, and computer skills) on a 1-5 scale (just like the O*NET).

Workers in Peru are less specialised than in the US

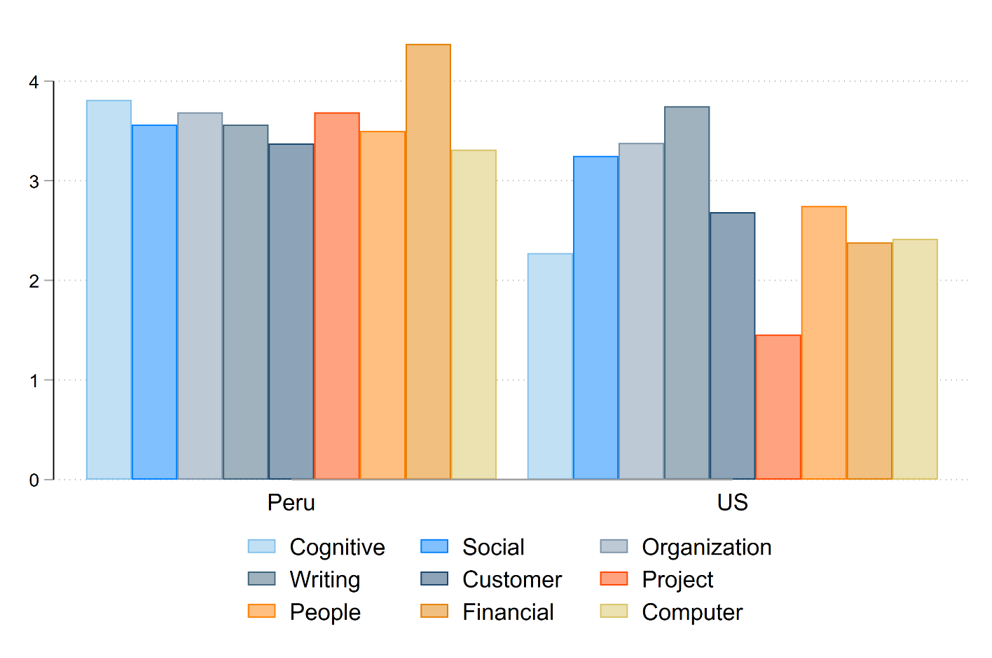

We compare occupational skill profiles in Peru and the US, and find that occupational skill profiles are substantially flatter in Peru — different professional figures do “a little bit of everything” instead of specialising in a limited set of core tasks. As an illustration, Figure 1 below compares the average importance of skills for one such occupation, accountants, across the two countries. In the US, accountants specialise in organisation and writing skills, but not so much in project management or cognitive problem-solving skills. Instead, in Peru accountants attribute more importance to every skill, including those that were less important for US accountants — hence the flatter skill profile.

Figure 1: Skill profiles of accountants in Peru and the US

Source: Authors’ calculations with SSERB-Peru and US O*NET

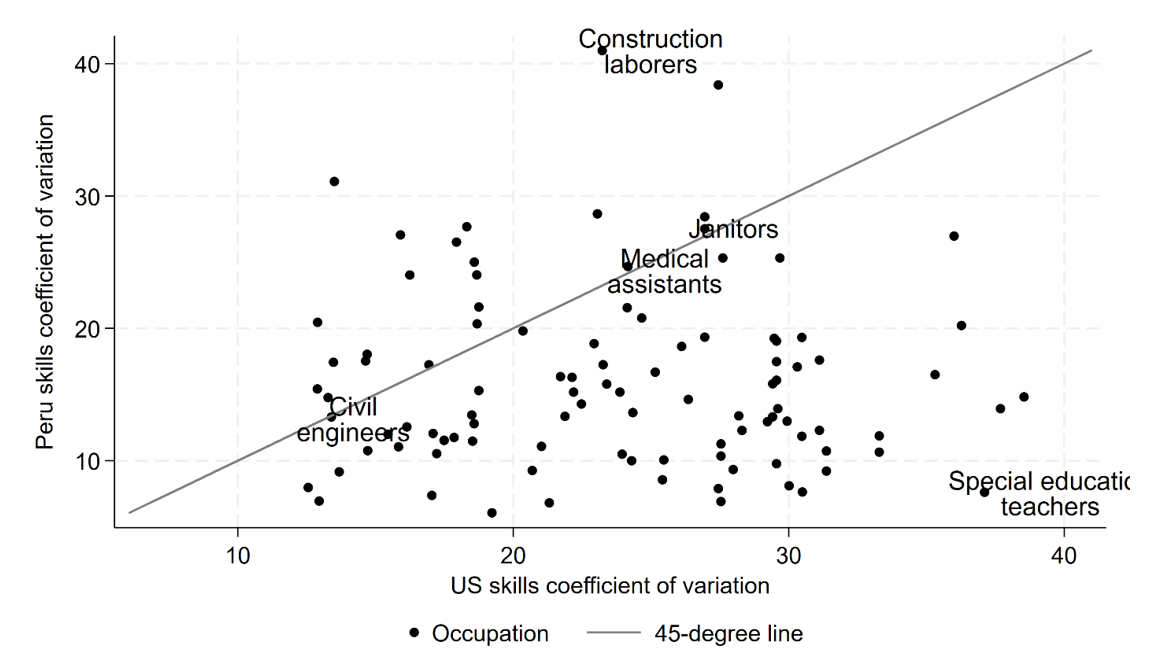

In our research, we formally measure this in several ways and conclude that we find similar patterns in most occupations. Figure 2 below depicts this fact. Each point in the scatter plot corresponds to an occupation average “coefficient of variation” (CV), which illustrates a variable’s degree of dispersion around the mean: with little dispersion, the coefficient is close to zero and the mean is a very good guess for any of the variable’s values. A higher CV represents a more specialised skill profile: when some skills are unimportant (value of 1) and other skills are extremely important (value of 5), a mean of 2.5 will be a poor predictor of either. On the other hand, flat, unspecialised skill profiles have the opposite characterisation: if all skills are somewhat important or important (a value of 2 or 3), a guess of 2.5 is much better a prediction than in the specialised case.

Figure 2: Most jobs in Peru have lower coefficients of variation and thus lower specialisation than in the US.

Source: Atencio-De-Leon, Lee, and Macaluso (2024)

Thus, the fact that occupational coefficients of variation are smaller in Peru reinforces the idea that Peruvian occupations are performed without skill specialisation. Or, in the words of Eduardo Galeano, Peruvian workers are toderos: “In Caracas, they are called toderos (do-it-alls), because they indeed do everything ; these marginalised workers live on occasional jobs, nibbling work bit by bit: they are servers or servants, stone-cutters or occasional masons, salespeople or street vendors, occasional electricians or plumbers or wall painters or car attendants; simply labor, available for whatever comes (Galeano, 1971, p.322)”. While the term toderos refers not only to marginalised workers nowadays, Galeano’s reference highlights its main meaning: the versatility of Latin American workers –for which we find evidence in our paper.

Does skill flattening come from inefficient hiring practices?

A lack of specialisation may come from inefficient hiring technology, yielding fewer and poorer matches between employers and employees than the same resources would produce in the US. To investigate this hypothesis we develop a survey of hiring methods and yields, which we fielded both in Peru and the US (Davis et al. 2021). We do not find evidence of inefficient hiring in Peru. Open jobs fill quickly, with an average vacancy duration of 9.1 days, and only 10% (1%) of vacancies remain unfilled after two weeks (four months). We also find very little appreciable difference in recruiting methods between Peru and the US. Our data confirms that the Peruvian labour market is fluid and that hiring procedures, unlike managerial ones as documented by Bloom and Van Reenen (2007), are not especially unproductive.

The uncertainty of labour availability explains firms’ hiring of unspecialised workers

Production tasks are often complementary. Kremer (1993) proposed the “O-ring theory”, where production tasks must be executed proficiently together for any of them to be of value. The name is a reference to the 1986 Challenger shuttle disaster; it exploded because it was launched at a temperature that caused one of those components, the O-rings, to malfunction. O-rings are small, mechanical gaskets, a seemingly insignificant part of a space shuttle. Yet, their malfunction led to disaster. Similarly, the O-ring theory of production postulates that output can be manufactured only if all inputs (in this case, skills) are present. As an illustration, one can think of the skills needed to turn on the light in a manufacturing establishment. Mastery of any specific task on the production line is of little use if workers and equipment lies in the dark!

When there is this type of complementarity in production tasks, high worker reallocation rates mean production losses. Employers are seldom sure what available labour they might find as they open their shops or come to the factory floor on any specific date, as idiosyncratic shocks affect workers and their access to transportation, child or elderly care, or their willingness or ability to work for pay. Thus, employers value workers who can perform many tasks to minimise disruptions to production. In the terms of our previous example, when employees are often absent or churn across jobs, employers need all employees to have the skills to turn on the factory floor lights — then, it doesn’t matter if someone is missing for production to happen.

In our research, we propose a stylised model that delivers a crucial insight consistent with this intuition: hiring generalists (“toderos”) becomes more profitable when the separation rate is high.

Conclusion: High turnover can inhibit specialisation

We document that jobs in Peru use a larger number of skills than comparable jobs in the US. The lack of specialisation is consistent with an environment in which skills are complementary in production and a fast-paced labour market, with frequent separations and hires, causing a preference for toderos (workers with many skills, do-it-alls). Together with evidence from the literature (Donovan et al. 2023), we find evidence that this is the case. We conclude that a brisk pace of job reallocation has the potential to significantly inhibit occupational skill specialisation, as we show is the case in Peru, potentially contributing to human capital and productivity deficits.

References

Atencio-De-Leon, A, Lee, M, and Macaluso, C (2024), “Does Turnover Inhibit Specialization? Evidence from a Skill Survey in Peru,” American Economic Review: Insights, accepted.

Bloom, N, and Van Reenen, J (2007), “Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4): 1351-1408.

Davis, S J, and Haltiwanger, J (2014), “Labor market fluidity and economic performance,” NBER Working Paper No. 20479.

Davis, S J, Macaluso, C, and Waddell, S R (2021), “How Do Employers Recruit New Workers?” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 21-28.

Donovan, K, Lu, W J, and Schoellman, T (2023), “Labor market dynamics and development,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(4): 2287-2325.

Feng, Y, Lagakos, D, and Rauch, J E (2024), “Unemployment and development,” Economic Journal, 134(658): 614-647.

Foster, L, Haltiwanger, J C, and Krizan, C J (2001), “Aggregate productivity growth: Lessons from microeconomic evidence,” New Developments in Productivity Analysis, University of Chicago Press, 303-372.

Galeano, E (1971), Las venas abiertas de América Latina, Siglo XXI Editores.

Hopenhayn, H, and Rogerson, R (1993), “Job Turnover and Policy Evaluation: A General Equilibrium Analysis,” Journal of Political Economy, 101(5).

Kremer, M (1993), “The O-Ring Theory of Economic Development,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3): 551-575.

Lagakos, D, Moll, B, Porzio, T, Qian, N, and Schoellman, T (2018), “Life Cycle Wage Growth across Countries,” Journal of Political Economy, 126(2): 797-849.