Providing information about the quality of placement agencies improves migration outcomes for job-seeking migrant women

Every year, millions of individuals from low- and middle-income countries migrate abroad on temporary work contracts (Mcauliffe and Triandafyllidou 2021). While these jobs afford workers the opportunity to earn significantly more than they would at home, they are often risky. Cases of domestic helpers and other low wage labourers suffering exploitation and abuse while abroad are documented with alarming frequency in the international press.1 Female migrants are especially vulnerable, as they are more likely to work in the homes of individual employers, where external oversight and access to assistance is limited. Many countries – including Indonesia, where our research is based – have struggled with crafting policy that minimises risks to migrants while preserving valuable income-generation opportunities, sometimes resorting to blanket bans on work abroad (Shivakoti et al 2021).

A key challenge facing policymakers in Indonesia and elsewhere is that it is difficult for potential migrants to assess the relative risk and returns from jobs available abroad. Partially due to these frictions, prospective workers rely on placement agencies to provide matches with employers, as well as job training. A recent study by Fernando and Lodermier (2021) in Sri Lanka found that much of the variation in migration outcomes can be explained by systematic differences in the quality of these agencies. Despite well-established work on intermediaries in goods markets (e.g. Ahn et al. 2011, Mitra et al. 2018), little is known about how such entities affect migrant labour markets and worker well-being.

In our study (Bazzi et al. 2022), we collaborated with Indonesia’s Board for Placement and Protection of Migrant Workers. We conducted a randomised trial to examine whether improving prospective female migrants’ access to information could help women select better service providers and enjoy safer migrations. The information was about the quality of migration placement agencies. Our findings indicate that information about agency quality induces women to make more deliberative migration decisions: fewer women migrate but with better agencies and as a result, those who do migrate have better experiences abroad. The research offers a new perspective on labour intermediaries and how information frictions shape international job search and migration outcomes.

Focusing on the role of placement agencies

Migration placement agencies play a key role in determining a worker’s migration experience. These agencies connect prospective workers to specific overseas employers, provide training to workers prior to departure and assist with issues workers encounter while overseas. Indonesia¬ – like many other migrant-sending countries – has a crowded migration placement marketplace where hundreds of legally registered agencies operate alongside many unregistered providers. These unregistered providers tend to be of lower quality. Even though potential workers have many agencies to choose from in principle, they lack information on agency quality in practice. This implies that they often opt to take the first job offer they get, delivered via middlemen who are affiliated with particular agencies and travel to rural villages in search of prospective migrants.

The design of the randomised trial in Indonesia

There are numerous agencies in the market and limited information available to potential migrants. We thus saw considerable scope for investigating whether information on agency quality can improve migration outcomes. Using data on migration outcomes of nearly 7,000 women interviewed as part of our baseline survey, we constructed quality ratings for 59 placement agencies. These agencies accounted for 75% of placements and baseline, and their ratings aggregated information on the quality of migrants’ pre-departure preparation (e.g., types and quantity of training received). It also aggregated information about monetary and non-monetary aspects of job quality (e.g., whether the migrant was given a weekly day off or was allowed to contact her family). We used these ratings to construct an agency report card which ranked agencies.

To complement the report card, we designed an infographic which displayed differences in average outcomes for women migrating with high- (upper quintile) versus low- (bottom quintile) quality agencies. We also designed an edutainment-style comic book which used the story of a fictional young woman interested in working abroad to explain the rationale for choosing a good agency and the hallmarks of a good agency. We developed these interventions in response to preliminary qualitative research which showed that many women considering working abroad didn’t consider the importance of choosing a high-quality agency or how migrant outcomes differ across those choosing high- versus low-quality agencies.

We then randomly assigned 400 of Indonesia’s largest migrant-sending villages to one of four treatment arms:

- 101 villages received the infographic, comic book, and report card

- 98 villages received the infographic and comic book

- 101 villages received the infographic and report card

- 100 villages received no information products at all

The materials were delivered via interactive community meetings run by a professional facilitator in partnership with a local facilitator from the community. For four years, we tracked a sample of 4,805 women who – at baseline – stated they were interested in migrating. We conducted interviews by phone for those abroad to understand the impact of our intervention on the migration rate and migration experiences.

The effects of providing information about agency quality

Our discussion here focuses on the effect of the provision of information on agency quality presented in the report card. We identify this effect while holding constant information about the returns to migration (provided in the infographic) and any general effects of holding community meetings. That is, we compare outcomes for villages that received the infographic, comic, and report card with those that received just the comic book and infographic.

1. Providing information about the quality of placement agencies lowers the migration rate

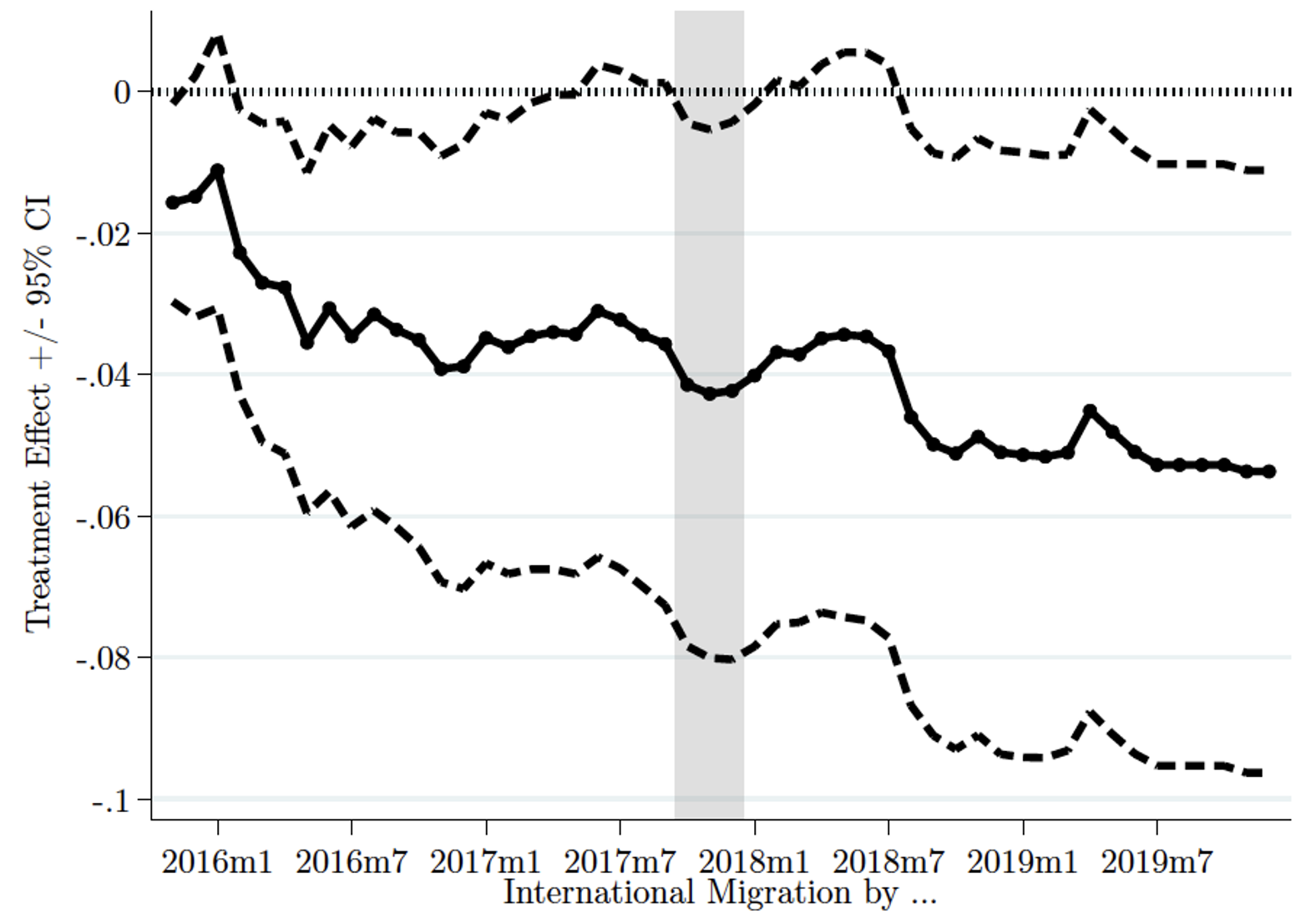

The information provided in the report card reduced the migration rate by 5-6 percentage points. Figure 1 shows how this decline materialised over time for women in exposed communities.

Figure 1 Impact of the report card on the migration rate over time

Note: This figure reports time-varying estimates of treatment effects on the migration rate. Sample includes 4,644 women in a tracking sample. The grey shaded bar denotes the second follow up survey which included a re-distribution of the report card. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals based on robust standard errors clustered at the village level.

Why would more information lead to less migration? Prospective migrants in Indonesia are extremely reliant on middlemen to connect them with agencies. Turning down an offer from one agency typically means the migrant will have to wait until another offer materialises in the future. Refusing offers – which women may do if information makes them choosier – thus reduces the migration rate at any point in time. In essence, information on agency quality made it possible and worthwhile for women to wait for a job offer from an agency of satisfactory quality. Women became more discerning in terms of which agency offers they would accept.

2. Women were more likely to accept jobs from verified and higher quality agencies

The report card reduced the likelihood of using a low-quality agency (bottom third of the grade distribution) by 13 percentage points. The use of high-quality (top third) providers increased by 11 percentage points. Women were also less likely to accept a job offer from providers who did not appear on the report card.

3. Migration outcomes improved

We find that using better quality agencies improved women’s migration experiences. Using summary indices, we find that pre-departure preparation (the quality of job training) and non-monetary aspects of migrants’ experience abroad (freedom of movement, ability to retain identity documents) improved significantly, by 0.17 and 0.10 standard deviation units respectively. There was no impact on pay but this is consistent with our observation that pay is largely determined by job type and destination country, which were unaffected. We also find no evidence that improved migration experiences reflect changes in the composition of the migrant pool, which could happen if the report card dissuaded women with high propensities to engage in ‘risky’ migrations.

Implications for migration policy

In summary, we find that providing information on placement agency quality in the form of a report card made women choosier when selecting migration offers and, in turn, improved migration experiences. However, this came at the cost of a lengthier job search and fewer migrations. Back of the envelope calculations, based on earnings in Indonesia and abroad, suggest that the average woman sacrifices nearly $200 USD (or half a month’s earnings abroad) to make more deliberate agency choices. Policymakers interested in improving migration outcomes without restricting access to high-return income generating opportunities must therefore work to ensure easy access to information on agency quality and a wide range of job offers (to reduce search time). Government oversight of quality-rankings and a system designed to reduce reliance on middlemen (for example, through a transparent central register of job opportunities) would tick these boxes. Quality rankings might also have broader effects if, in the long term, they lead under-performing agencies to either exit or reform. Such general equilibrium effects were beyond the scope of our study but are an important area for future research.

References

Ahn, J B, A K Khandelwal and S J Wei (2011), “The role of intermediaries in facilitating trade”, Journal of International Economics, 84 (1): 73–85.

Bazzi, S, L Cameron, S Schaner and F Witoelar (2022), “Information, Intermediaries, and International Migration”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16811.

Fernando, N and A Lodermeier (2021), “Understanding Adverse Outcomes in Gulf Migration: Evidence from Administrative Data from Sri Lanka”, International Migration Review.

Mcauliffe, M and A Triandafyllidou (eds.) (2021), World Migration Report 2022, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva.

Mitra, S, D Mookherjee, M Torero and S Visaria (2018), “Asymmetric information and middleman margins: An experiment with Indian potato farmers”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 100(1): 1–13.

Shivakoti, R, S Henderson and M Withers (2021), “The migration ban policy cycle: a comparative analysis of restrictions on the emigration of women domestic workers”, Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1): 1–18.