Deportation policies can inadvertently disseminate ideas and criminal networks between countries, unintentionally increasing migration back to the US

Although several governments have enacted strict measures targeting gangs, the historical factors underlying their growth have been largely overlooked. In this context, the spread of gangs along migration corridors has been attributed to US deportation policy (Ambrosius 2021). This unintended consequence of deportation can result in the proliferation of gang activities which include violence, drug trafficking, extortion and human smuggling.

In 1996, the US Illegal Immigration Responsibility Act suddenly increased the number of deportations with members of large gangs (MS-13 and 18th street) founded in Los Angeles being sent back to El Salvador. In a recent paper (Sviatschi 2022a) exploring the exportation of US criminal capital to El Salvador, I find evidence that US deportations led to an increase in homicide rates and gang activity in El Salvador. In addition, deportations also resulted in increased gang recruitment and migration of Salvadoran children.

Deportation from the US to El Salvador

During the 1980s, Salvadoran children joined the aforementioned gangs in Los Angeles where many families had migrated after El Salvador’s civil conflict. Though these gangs were not extremely violent initially, after spending time in US prisons, members gained skills related to extortion and violence. The 1996 change in deportation policies sent gang members back to their home countries where most deportees returned to their birth municipality. This setting yields three useful sources of variation: (i) geographical variation in the location of US gangs in El Salvador and deportees’ birthplace, (ii) over-time variation in criminal deportations in the US, and (iii) variation in the age of exposure of Salvadorian children to gangs. By comparting changes in outcomes between birth and nonbirth municipalities in El Salvador, I can measure how the arrival of gang members from the United States affected US gang-related activities (extortion and drug trafficking), homicide rates, and child recruitment before and after the change in policy. The idea is that gang deportees’ arrival had a larger effect in municipalities where they settled, which can be predicted by their places of birth, and that within these areas, it affected young children more given that gangs heavily recruit children less than age 15

US deportation policy and gang activity in El Salvador

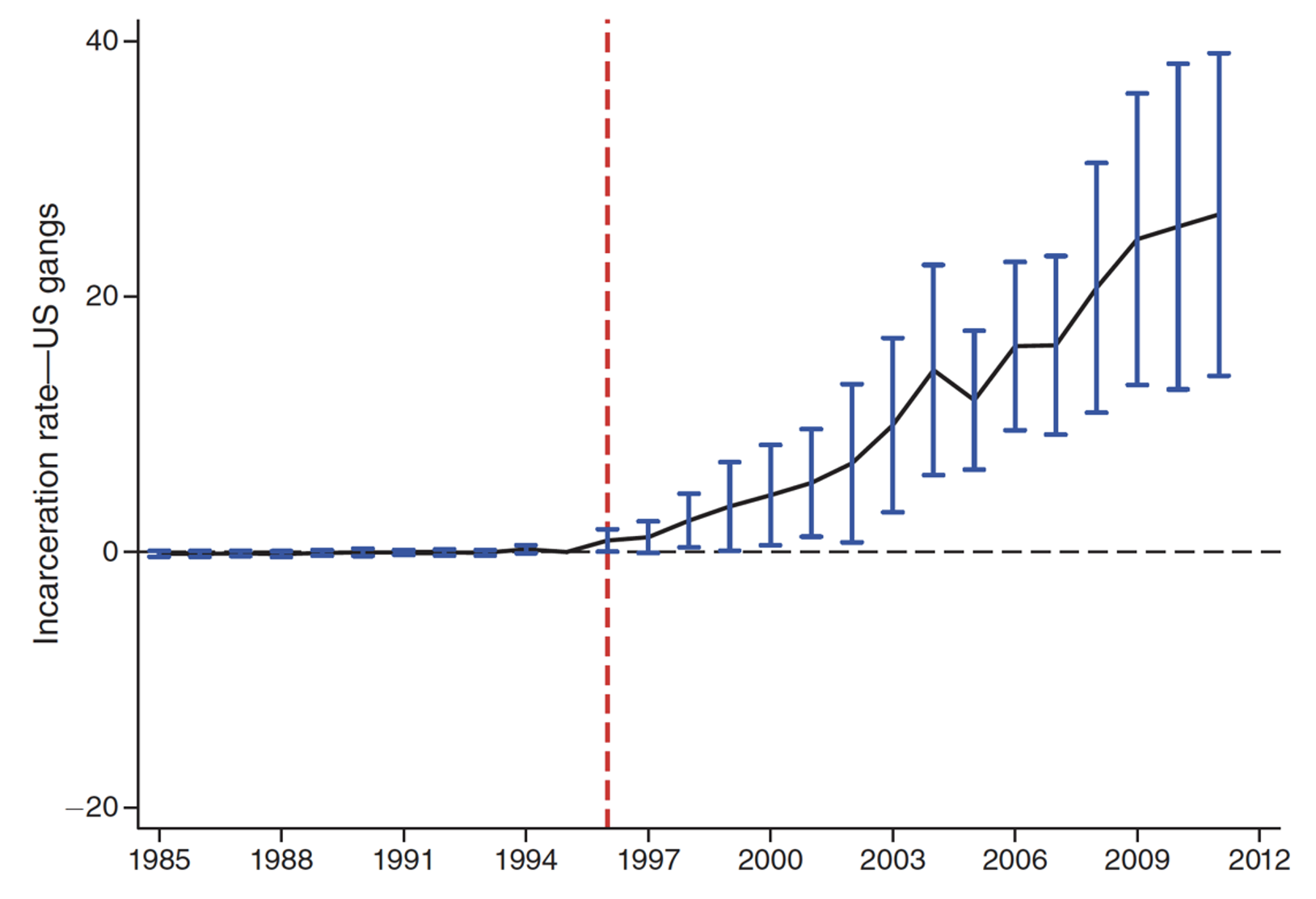

My results found that gang activity in El Salvador was positively associated with US deportation policy. Figure 1 illustrates that the number of incarcerated individuals affiliated with US gangs sharply increased in municipalities that received deportees between 1996 and 1997 relative to those that did not.

Figure 1 Incarceration rate of US affiliated gang members in El Salvador

US deportation policy and crime in El Salvador

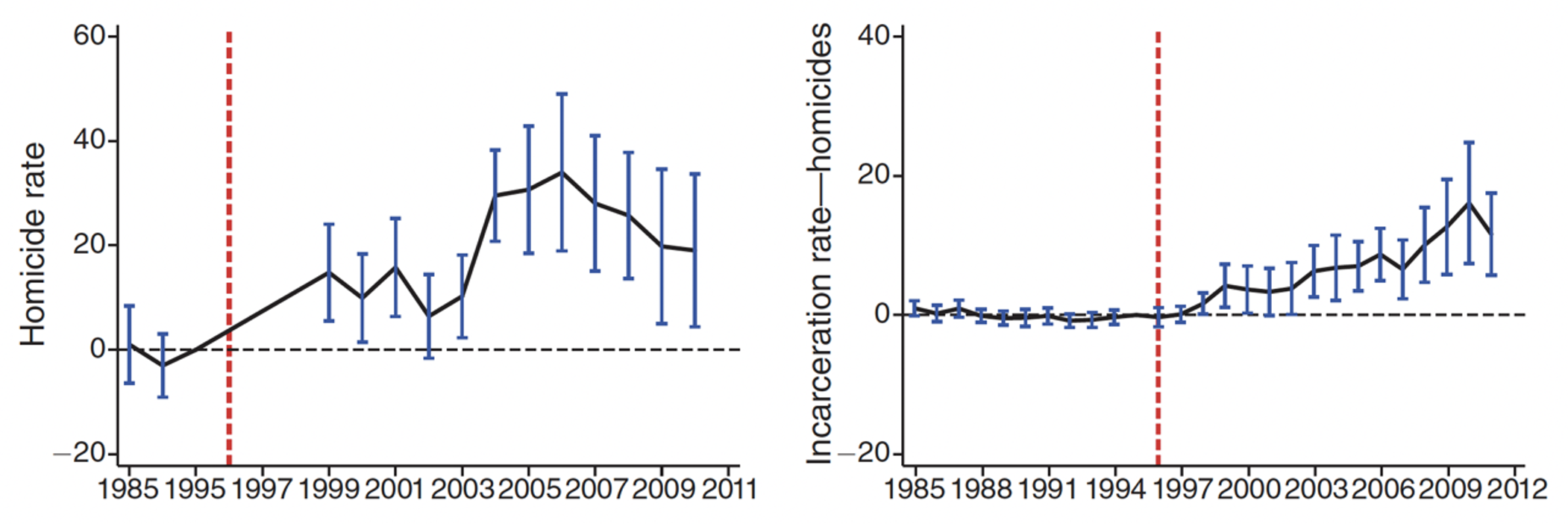

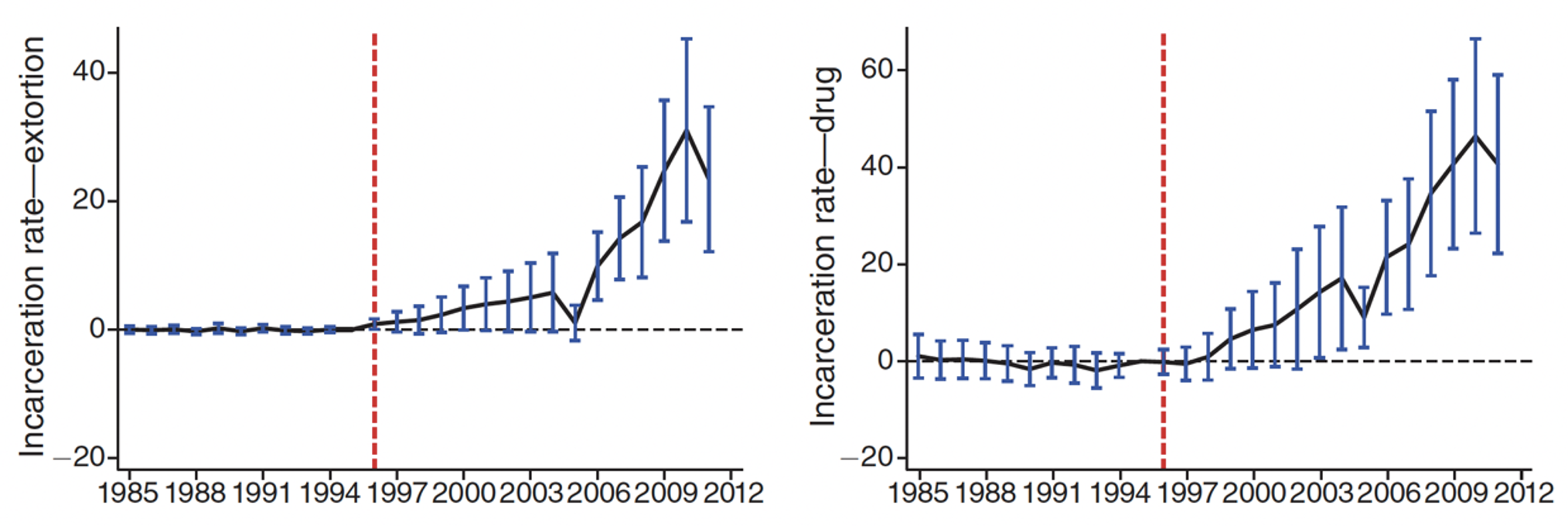

I also explored the extent to which increased gang activity translated to spikes in gang-specific crime in El Salvador. Extortion and drug trafficking activities double, and violence increases by 40% between 1985 and 2011. Similarly, incarceration rates with US gang affiliation, increased by a similar magnitude in the same time frame, as shown in Figure 2.

Conversely, incarceration rates for non-gang related crime did not exhibit any abnormal dynamics in deportees’ birth municipalities. This suggests that legislative changes, enforcement conditions, and policy changes cannot explain the results. I find that my main results are not driven by an increase in non-criminal deportations, deportee’s exposure to violence during the civil conflict, nor negative selection of immigrants to the US (such as violent individuals migrating to the US in the first place). Therefore, this implies that crime in El Salvador only increased due to the deportation of gang members from the US.

Figure 2 The 1996 shock and crime

A) The 1996 shock and homicide

B) The 1996 shock and gang specific crime

Gang recruitment of children

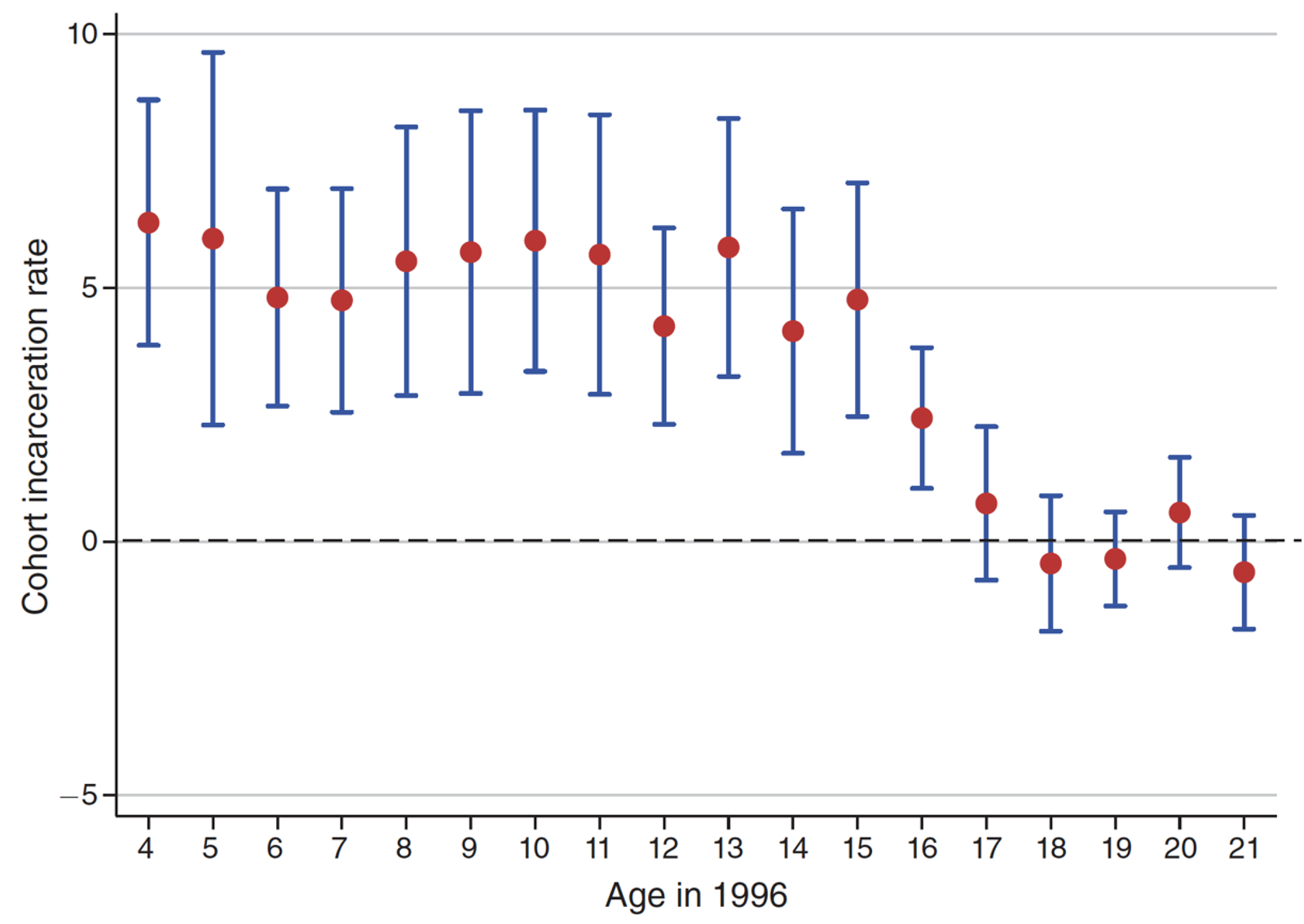

Having found increases in gang activity in El Salvador, particularly in crimes requiring intensive gang-specific human capital, I analyse the extent to which deportee’s negative spill-over effects in Central America include not only the proliferation of criminal knowledge but also the recruitment of native children into the gangs. I exploit the variation in exposure of Salvadorian children to gangs by cohorts of birth.

Figure 3 shows the incarceration rate effect by cohort. I find that individuals who were born in gang deportees’ birth municipalities and were younger than 15 when US gang members arrived were more likely to be part of a US affiliated gang in adulthood. This result is consistent with the fact that the usual age of initiation into gangs is between 10 and 14, when children are looking for a social structure that US-affiliated gangs can provide. In particular, I find that the affected cohorts are 20% more likely to be incarcerated for gang-related crimes as adults, compared to less-exposed cohorts (e.g. individuals who grew up in non-birth municipalities and individuals who grew up in gang deportees birth municipalities but were older when the gang deportees arrived).

Figure 3 Incarceration rate effect by age

Mechanisms behind gang recruitment

I also investigate whether the effects of gang member deportation on child recruitment depend on the pre-existing characteristics of municipalities most affected by the increase in criminal deportations from the US. Neither the baseline number of police officers, state officials, or army bases in the 1980s appeared to mitigate gang recruitment in the 2000s. In contrast, the effect of US deportations on gang recruitment are mitigated in municipalities with historically stronger social ties and networks, which are part of the criminal capital brought by US deportees. These results suggest that increasing police enforcement may not be sufficient to halt child recruitment. US affiliated gang deportees brought not only violent skills but also a social structure for children.

Policy implications: The role of gang violence in El Salvador in International Child Migration

Having established the link between US deportees, increased gang related crimes and recruitment of children in El Salvador. I also study the relationship between homicides and international child migration. I find that an increase of one homicide translates to an increase of two children deported from other countries back to El Salvador per month. This implies that deportation policies may generate a self-reinforcing cycle of migration, gang recruitment, and violence.

There are three main findings to keep in mind for policy response:

- First deportees from the US brought new criminal knowledge related to extortion and drug dealing which led to the development of gangs and violent crime in El Salvador.

- Second, gang deportees may have spread their criminal capital in El Salvador by recruiting children with no previous exposure to US gangs.

- Third there is some evidence suggesting that gang deportation increases child migration from violent gang areas in El Salvador to the US which in turn increases deportations. That is, it generates a self-reinforcing cycle of deportations.

The policy implications of these results are manyfold. First, they shed light on the debate over whether unaccompanied child migrants should qualify for legal status as refugees in the US since the could be fleeing violence. The findings suggest that policymakers should examine long-run solutions to gang activity that seek to break the deportation and criminality cycle. Some of these include addressing the incentives that children face when deciding whether to drop out of school and join gangs. Or using conditional cash transfers as a policy alternative to achieve this goal (Sviastchi 2022b). Finally, the results show by deporting migrants with criminal capital and connections, the US is increasing further migration issues. This highlights the need for better reintegration of migrants and ex-convicts as a tool to break the cycle.

References

Ambrosius, C (2021), “Deportations and the transnational roots of gang violence in Central America”, World Development 140: 105373.

Cruz, J M, J D Rosen, L E Amaya, and Y Vorobyeva (2017), “La nueva cara de las pandillas callejeras: El fenómeno de las pandillas en El Salvador”, repo.funde.org.

Sviatschi, M M (2022a), “Spreading Gangs: Exporting US Criminal Capital to El Salvador”, American Economic Review 112(6): 1985-2024.

Sviatschi, M M (2022b), “Making a NARCO: Childhood Exposure to Illegal Labor Markets and Criminal Life Paths”, Econometrica 90: 1835-1878.